Across the nation, students are making it clear to their universities that the curriculum they are learning every day is insufficient for the 21st century. Recognizing a rift between the words written on a chalkboard and the society that lies outside the classroom door, these students are increasingly pushing for a course of study that allows them to learn about traditionally underrepresented figures and reckon with concepts of oppression and justice. For this, they look to ethnic studies.

Ethnic studies is an interdisciplinary field devoted to the examination of race and culture in U.S. history and contemporary society. It came to the fore with the growing racial consciousness that defined the 1960s. In 1968, Brazilian educator Paulo Freire published a groundbreaking body of work called the “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” charging traditional educational institutions with indoctrinating hierarchies of power within the classroom setting. That same year, one hemisphere over, a wave of youth and faculty at San Francisco State University initiated the Third World Liberation Front movement — it is historically unclear whether they had read Freire’s work, though they share the same thread of ideas — to advance the cause for ethnic studies. Soon, waves of students would be storming the campus of not only SFSU, but also the University of California, Berkeley and the University of Minnesota, among others. These schools succeeded in developing a lasting pedagogical architecture for ethnic studies, paving the way for universities to do the same.

In the 21st century, the legacy of this effort has continued on in pockets of the United States, though ethnic studies programs vary greatly from university to university. In no two places has the discipline emerged in the same way — some schools have established separate departments and research facilities for ethnic studies, while others remain without a major. Harvard College is one of the latter. As we examine our own efforts to establish an ethnic studies department at Harvard, looking at the work other schools have already done to achieve the same goal can help. This comparison not only shows that Harvard is behind many of the other universities in the United States, but also offers pathways for Harvard ethnic studies advocates to follow.

On the Home Front

At Harvard, students advocate for ethnic studies as a more complete representation of this nation’s history, which they have found to be lacking in traditional university curricula. “I grew up hearing Border Patrol helicopters overhead, and that was just a fact of life. Reading these texts made me feel seen,” Raquel Rivera ‘23 told the HPR, speaking to the curricular texts of Spanish 126: Performing Latinidad. Rivera is one of the organizers for the Harvard Ethnic Studies Coalition, a collective of current Harvard students and alumni pushing for the creation of an ethnic studies department. But for Rivera, the significance of ethnic studies was far more than personal. “Beyond that and more importantly, ethnic studies … is a way to improve our understanding and critique our understanding of race, ethnicity, and other power structures.”

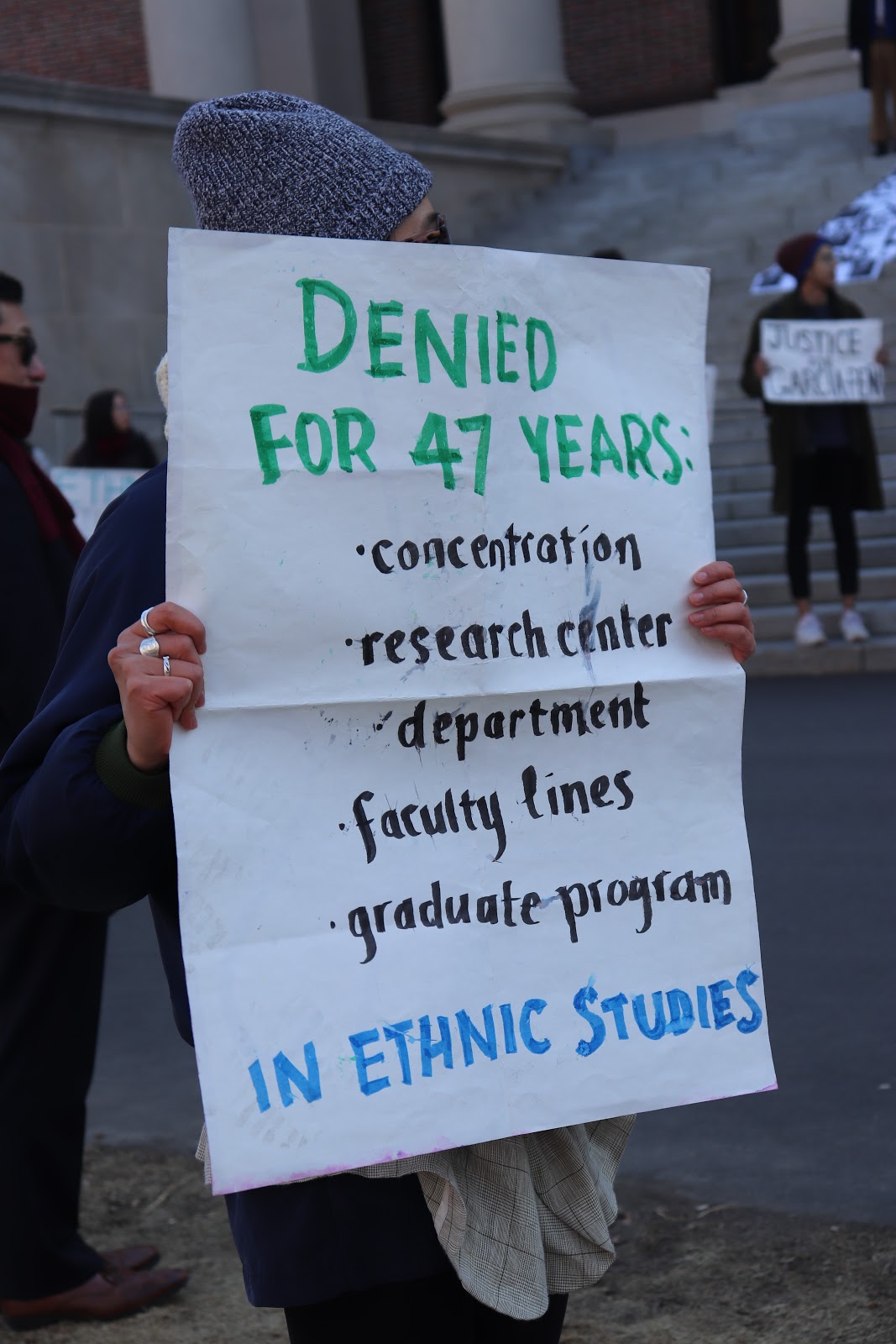

The first call for a track of study dedicated to a particular racial group at Harvard came in the 1960s, setting off decades of resistance that continues today. In 1969, the college established the African and African American Studies Department, then called the Afro-American Studies Department, in response to increasing student unrest catalyzed by Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination. Four years later came the first proposal for an ethnic studies program from then-Harvard history professor John Womack. Eleven more proposals would come as the years went on, but action remained slow. Faculty and student opposition argued that the discipline would garner little interest, that it was a form of self-segregation, and that it was a political rather than academic undertaking. Administrators also pointed to a lack of sufficient funding in the arts and humanities to support the creation of the program.

Finally, in 2009, Harvard established the Committee on Ethnicity, Migration, and Rights, an achievement that former Undergraduate Council President Andrea R. Flores described as “10 [or] 20 years in the making.” The committee offers two different secondaries, one entitled Ethnicity, Migration, Rights and another entitled Latina/o Studies that focuses specifically on studying the Latinx population within the United States. The secondaries remain popular among Harvard students, with 78 currently declared across the two fields during the 2019-2020 school year, according to the committee’s Administrative Director Eleanor Craig.

Nevertheless, a committee is insufficient. Rivera cited the importance of having a department that would also offer undergraduate concentrations and graduate-level degrees, grant professors independent hiring power, and provide greater transparency in the tenure selection process. “The most important thing is that the discussion happens, and right now I don’t think we have that sort of discursive space that has been given value,” said Ajay Singh ‘21, who is also an organizer for the HESC, in an interview with the HPR. While the creation of a department is a primary goal, student activists also wish to see the university invest in an analogous research facility to explore ethnic and racial formation. As of now, Rivera said, “Harvard might be producing groundbreaking work in ethnic studies, but it’s less Harvard and more so professors like professor Lorgia García Peña.” Singh added, “If a department or program has a research center, it means that there is funding that has been allocated for faculty … to pursue cutting edge research, given value beyond their teaching.”

The movement for a full department has been active for at least four decades, cycling through waves of activism and reform. In the most recent wave of ethnic studies activism, the Task Force for Asian American Progressive Advocacy and Studies, formerly named the Task Force for Asian and Pacific American Studies, coordinated many of the early efforts and laid the framework for a cross-community coalition that would become the HESC. The HESC had largely escaped the attention of the student body until the denial of tenure to García Peña, professor of Romance Languages and Literatures, in November 2019.

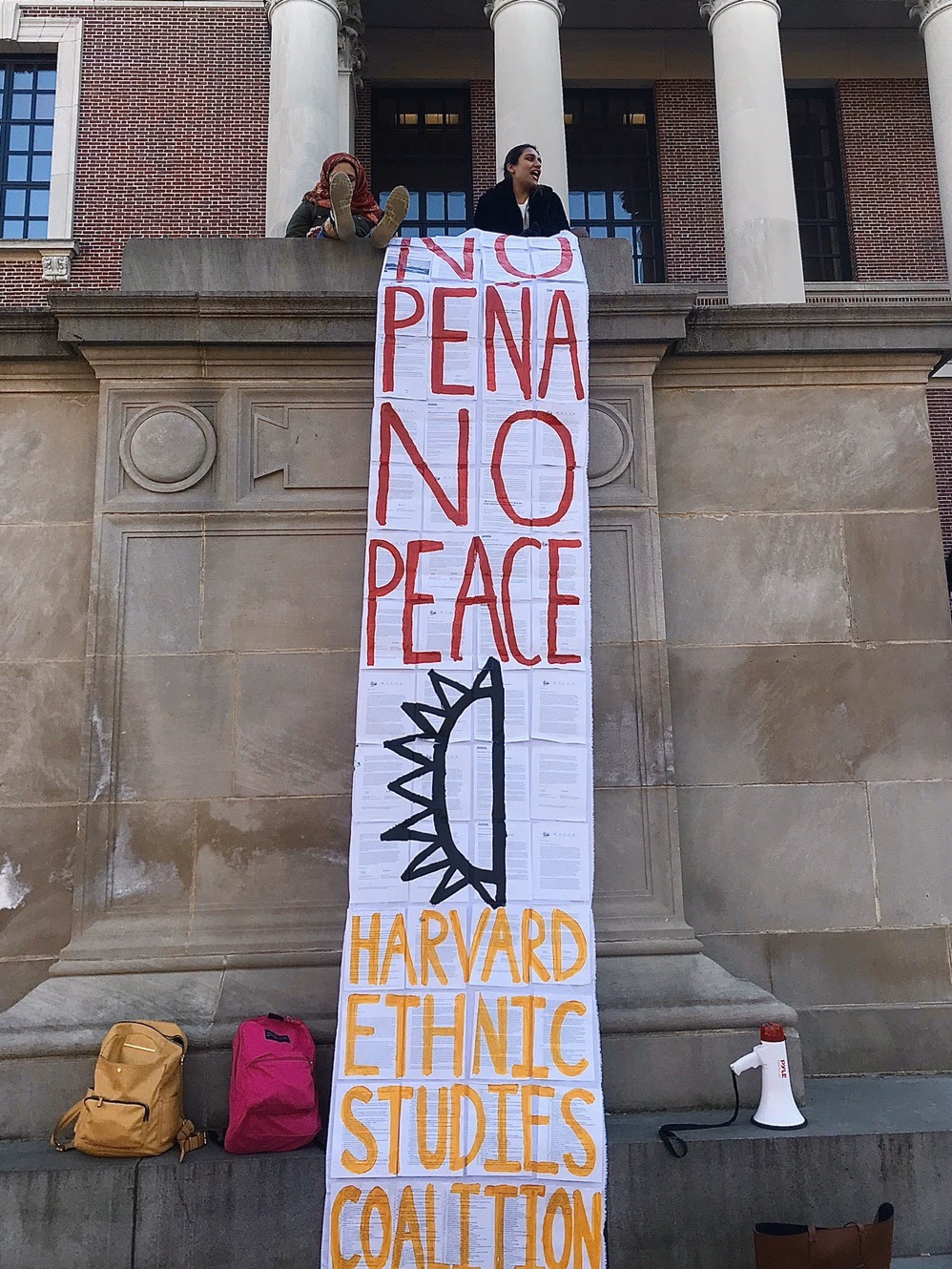

Soon after the denial, HESC emerged in the foreground of student activism efforts, drawing together a broad base of students, affinity organizations and political groups in support of García Peña. Harvard students and community members published a statement immediately after the incident, gaining 285 signatures and the support of 53 campus organizations. Some voiced their discontent through protests outside Widener, donning black caps demanding “Ethnic Studies Now!” and carrying posters reading, “Justice for García Peña.”

Students drop a banner from the Widener Library steps during a protest.

A sign detailing the history of ethnic studies activism at Harvard.

Students support Professor Lorgia García Peña, who was denied tenure in late 2019.

In addition to these student efforts, over 200 professors from all over the country responded by publishing a letter addressed to President Larry Bacow in which they cited Harvard’s failure to recognize García Peña’s significant contributions to the field as well as a lack of institutional support granted to faculty members of color more broadly, many of whom nevertheless conduct research on their own. As scholars from various fields of ethnic studies and gender studies, they wrote that the denial of tenure signified that “despite increasing demands from students, these areas of study are not intellectually significant in the tenure process.” Similar letters of support for García Peña continued to pour in from the American Studies Association, the African American Intellectual History Society, and various other individuals and organizations.

On campus, the HESC plans on furthering their advocacy despite the uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. Singh said that the movement was planning to pursue different avenues of activism by producing digital content, organizing video forums, and utilizing social media. “I’m excited,” Singh said. “I’m a little wary but I’m nervously excited, I guess, because there’s a lot of creativity that we haven’t accessed yet in terms of digital media. There are a lot of possibilities.” As the campaign continues through the coronavirus pandemic, Singh reports that student activists remain optimistic about their efforts to create the discursive space that Singh and others would like to see. In the meantime, however, Harvard still has much progress to make — especially compared to other institutions across the nation.

A West Coast Success Story

On the West Coast, ethnic studies arrived more than fifty years earlier as an outgrowth of the Civil Rights Movement. While the infrastructure for the course of study continues to evolve, it nonetheless provides a strong example for colleges around the nation.

San Francisco State University was the first school in the nation to establish a College of Ethnic Studies in 1969, a product of insistent and dynamic student activism. SFSU is still the only university in the nation to dedicate to ethnic studies an entire “college,” an apparatus that houses multiple departments representing distinct pathways for the study of various racial and ethnic groups. The dean of SFSU’s College of Ethnic Studies, Amy Sueyoshi, told the HPR, “A number of people have posed the question, ‘Why did it happen at [SFSU]? Was it because the student organizing was particularly effective, or because the students were particularly radical?’ The strikers consistently say that it was pretty good coalition building across all the different constituents at the university.” Beginning in 1968, the TWLF campaign put together what would become the longest student-led strike in United States history, a five-month effort demanding a curriculum and faculty which represented more voices of color. The movement would spark many more across the nation, and according to SFSU, by the year 1978, 439 colleges in the country would collectively offer 8,805 courses in the field of ethnic studies.

The impetus that propelled such a broad change in pedagogy nationally still runs strong in the school today. Joyce D. Bantugan, a current senior at SFSU, remembers entering campus as a freshman in 2016 and witnessing hunger strikes that tried to draw attention to budget cuts within the College of Ethnic Studies. In an interview with the HPR, Bantugan said, “It really struck me because it really showed the power that students have in academics and curriculum, and it showed what community building can really do.”

Bantugan would soon come to realize what exactly the students were advocating for after her first ethnic studies experience in SFSU. Bantugan had not formally learned about her cultural background in any way before coming to the university. “If I recall correctly the one time I remember reading about Filipinos was about Cortez and the spice trading,” she told the HPR. “That was the one time I remember ever hearing about Filipinos in any textbook, I kid you not.” Bantugan soon enrolled in the course “Asian Americans in History” in the spring of her freshman year. “I started to realize just how big of an impact Filipinos had in California, in the United States, and so forth. That fueled my hunger to learn more about my culture, about my history.” This sense of recognition Bantugan had while studying her own culture is a central element of SFSU’s program, one that aims to teach students about both their own place in society and that of others.

The college prides itself on featuring a diverse array of voices and perspectives within its classes. Sueyoshi emphasizes the importance of making sure the educators themselves represent these voices, with 65% of the faculty being women of color — the national average sits at 11%. Meanwhile, at Harvard, underrepresented minority women constituted only 3% of tenured faculty members in 2019. At SFSU, this diversity is further reflected in the curriculum, with the college even offering a quantitative reasoning course that Sueyoshi jokingly refers to as “ethnic studies math.” While ethnic studies and math may seem an unlikely pair, Sueyoshi explains: “It’s a class that makes us delve into the data to look at the numbers more carefully and think about what they mean.” By studying how the tools of data and statistics can be leveraged to understand the position of communities of color in modern society, the course makes a case for subjectivity in the traditionally “objective” world of numbers. The course is seated within a larger tradition that takes a holistic approach to race and ethnicity, bringing identity out into the open in order to critically examine it. Finally, a necessary complement to SFSU’s holistic pedagogical approach to the field is Community Service Learning, which integrates classroom learning with experience in the field and enhances the relevance of an ethnic studies education for students.

All of these features of SFSU’s culturally-relevant education have had substantial impact. Majors within this college graduate at rates 25 percentage points greater than the average for non-ethnic studies majors. In addition, even nonmajors who take at least one course within one of the five ethnic studies departments graduate at higher rates than those who do not. Bantugan affirmed this: the College of Ethnic Studies not only increased her participation in school but also increased her participation within the community. All this is accomplished without the significant monetary cost that critics of ethnic studies departments elsewhere often point to. Sueyoshi stated, “The irony is that [California State] … [is] a poor, poor university system. San Francisco State University also is super poor among all the other campuses. If San Francisco State University … can find funds to offer ethnic studies courses, then almost any other school could do the same. I firmly believe that.”

Institutions with the Most Degrees Awarded in Ethnic Studies

Source: DataUSA.io

SFSU’s success has been paralleled by other schools across the West Coast. In the year 2017, while schools in the four states of California, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington collectively awarded 200 degrees in ethnic studies, the remaining swath of states across the nation awarded only 121 degrees. Even at the high school level, Stanford researchers Emily Penner and Thomas Dee found that participation in an ethnic studies course reduced unexcused absences by 21 percentage points and increased students’ GPAs by 1.4 points. The results that came back surprised Penner herself, as she shared with the HPR: “We thought they couldn’t possibly be right. They were so large, we didn’t expect them.” When asked about why these programs have been able to hold in West Coast schools, Sueyoshi pointed to a heightened racial consciousness that has emerged from the unique history of the West. Though the West Coast has its own racial problems, cities like San Francisco and Los Angeles have greater levels of racial integration than New York or Philadelphia, allowing for the creation of what Sueyoshi calls “a people of color consciousness.”

The relatively rapid rate of movement across the West Coast has drawn attention to the chasm of progress that schools like Harvard and Yale still have to cross. “It reveals the fundamental contradiction wherein if universities like Harvard and Yale invest in ethnic studies, they’re basically investing in their own destruction,” Yale senior Janis Jin said in an interview with the HPR. “I think that’s precisely why it’s so hard to get funding and support from schools like Harvard and Yale, and it’s much easier in public institutions.” Perhaps West Coast schools are less entrenched in a history of colonialism and slavery, and rely less on its legacy of endowments. After all, UC Berkeley was founded in 1868, SFSU in 1899, and the University of Oregon in 1876. Harvard was founded in 1636, when what would become the United States was enmeshed with colonialist enterprises; the university was explicitly sustained by the slave economy for the first 150 years. Then, for years after, it featured professors such as Louis Agassiz and Nathanial Shaler who promulgated “race science” that upheld white supremacy. A study of this history would invariably mean the uncovering of our own checkered past and present. “It’s honestly a bit shameful and hypocritical of Harvard,” said Rivera. “In this global stage we talk about how far we’re ahead of the pack, but in reality we are really far behind. We are not even a blip on the radar.”

The Real Harvard-Yale

In order to understand where Harvard stands, it might also be helpful to look toward New Haven. Harvard and Yale have been both peer and rival schools for centuries, always seeking to surpass one another — and when looking at ethnic studies, it seems that Yale has gotten much further than Harvard.

At Yale, while ethnic studies lacks a departmental presence with a central faculty and greater resources, it takes the form of a distinct program called Ethnicity, Race, and Migration. For most of its 20-year history, it existed solely as a major, until heightened demand in the last decade led the university to formalize the program with more faculty positions and the creation of a corresponding research facility called the Yale Center for the Study of Race, Indigeneity, and Transnational Migration. Jin sees this major as a way for students to understand and examine the world around them, something that has become more and more relevant against the backdrop of racial tensions within the United States. She told the HPR, “Racism is not really about microaggressions and cultural appropriation and those sorts of things as much as it is, in a very literal way, something that determines whether you live or die in a lot of instances. I think that raised the stakes of everything for me and at Yale.” In particular, Jin was drawn to the discipline in search of answers after a 2018 incident of racial profiling, when a police officer previously involved with Yale fired at an unarmed Black couple just outside of the university.

Much of the recent advocacy work on Yale’s campus was in response to what students saw as the unfair denial of tenure to ERM professor Albert Laguna. Six months before her own denial of tenure at Harvard, García Peña wrote an editorial in April of 2019 on the implications of Yale’s decision.

“White supremacy in these institutions bleeds through the photos of white men which hang in the halls of the university, in the syllabi that privilege white cannon and lack any type of representation for people of color, and in the university’s inability to hire or retain black and brown faculty, in the university’s disavowal of Ethnic Studies as a legitimate field of knowledge.”

Responding to Laguna’s denial of tenure and additional institutional shortcomings such as the programs’s lack of hiring power or departmental corpus, 13 senior faculty members stepped down from ERM. Professor Daniel HoSang, one such dissident, said in an interview with the HPR, “We withdrew our labor from the program because we found the university’s model for supporting it unsustainable. No one essentially had a formal appointment in ERM, so we were splitting our time between the [things] we were appointed in and ERM, and it didn’t allow us to properly advise, support, and teach students, or conduct our research.” As it did in Harvard, this denial of tenure served as a catalyst to bring out much larger structural problems into the open.

In response to the immediate wave of protest, Yale came to a resolution that granted the program independent hiring authority and a greater role in the tenure promotion process. Singh commented that Yale professors were able to hold this leverage in a way that Harvard professors could not because of the presence of a formalized program. “There isn’t a central way for faculty [at Harvard] to express the kind of solidarity that the Yale faculty were able to express and leverage to get Yale to follow their demands.”

While Yale has acquiesced to certain student demands and strengthened the department, the ethnic studies discipline is far from where students imagine it could be. Students specifically point to a lack of faculty to support growing student demand for the field. Jin noticed this herself with respect to seminar classes, saying, “I’ve had to apply for almost every single ERM seminar. … You have to write an application saying, ‘I deserve to be in this class.’” She continued that this was an experience she has had only within the ERM department, whereas comparably popular English courses seemed to have enough faculty to sustain multiple sections.

HoSang pointed to one possible reason for the often relatively slow action on this front: The administrative infrastructure of higher education, he said, is generally slow to respond to student activism because of the separation between the static administration and dynamic faculty and students. However, there is a notable exception. “The interesting thing is that universities are quite responsive in the STEM fields, where people understand that innovation and interdisciplinary collaboration inside and outside the university are critical.” Putting this next to what HoSang terms the “really lethargic response” to the formation of an ethnic studies department reveals discrepancies in the administrative treatment of different fields. Administrators, instead, should give the same thought to the creation of an ethnic studies department as it would to any other.

While there are certain features of Yale’s ERM major that students wish to see improved, Harvard has much to learn from the New Haven university: in particular, the importance of building a structure that supports and retains a strong faculty base within the field of study.

A Larger Dilemma

Ethnic Studies Degrees Awarded by Institution

Source: DataUSA.io

In Lansing, the home of Michigan State University, a refugee center hosts a significant number of refugees hailing from Cuba. Here, the vibrant migrant community has also underscored the need for ethnic studies. As professor Miguel Cabañas, who teaches Chicano/Latino studies at Michigan State University, said in an interview with the HPR, migrant workers of the 20th century would travel in a circle across the United States, from California to the midwest to Florida and Texas, in search of work. “It’s not an easy thing to teach, and it’s not an easy thing for people to learn, but knowing that history, people will understand why migrants are here.” In this way, ethnic studies provides a way for Cabañas and his students to reconcile the academic experience with the developments of our contemporary world.

One feature of Michigan State’s approach to ethnic studies that separates it from that of many other universities is the creation of distinct departments for each racial or ethnic group. “We have nothing in common,” Cabañas said. “We’re not in the same area, we’re in different colleges.” While Chicano/Latino Studies is seated within the College of Social Sciences, African American & African Studies and Indigenous Studies fall under the College of Arts & Letters. This type of separation, says Cabañas, disjoints the fields of study that might otherwise find greater strength in unity: “By having all these in an umbrella, it could help us pull in the same direction and create programming that can be useful for the different ethnic programs.”

While Michigan State’s materialization of ethnic studies as a discipline has emphasized the importance of integrating ethnic studies across areas of study, the University of Minnesota has emphasized the importance of research. Ethnic studies at the University of Minnesota is not identified by that name; instead, it comprises various departments focusing on different identities that come together with the Race, Indigeneity, Gender & Sexuality Initiative. The RIGS Initiative focuses on building a strong research community that facilitates discourse on issues of power, inequality, and social change.

In an interview with the HPR, professor Tade Okediji, chair of the Department of African American & African Studies at the University of Minnesota, cited the importance of a research center as an “incubator to talk about issues and challenges from multiple dimensions, the issues and challenges at the intersection … of race, class, gender, sexuality studies.” Okediji adds that one of the central components of such a research center is inviting academics from diverse fields of study to enter a cohesive dialogue and pursue “coherent research agendas that are relevant to contemporary society.”

Ethnic Studies Degrees Awarded by County

Apart from Michigan State and the University of Minnesota, numerous other universities across the nation have worked to instate some form of ethnic studies. The University of South Florida features an Institute for the Study of Latin America and the Caribbean, underscoring the importance of situating a course of study within the local context of the university. At Brown University, which grants the most degrees in the field outside of the West Coast, a concentration allows students to choose to focus on a particular aspect of the lived experience of communities of color — this encapsulates a broad range of themes such as health, diaspora, and inequality. The expansion of ethnic studies offerings is slowly becoming visible in the workforce as well; the number of people in the workforce with a degree in ethnic studies is currently at 166,893, but the number has been increasing by 3.67% in recent years. What Harvard has to learn is the importance, as Cabañas said, of not just touting “vague ideas of diversity” but making the institutional commitment to ensure that diverse voices and perspectives are represented in the academic experience.

Harvard, take the lessons that other universities are giving you: look to SFSU for community engagement, to Yale for structures of faculty support, to Michigan State for integrating various areas of study within ethnic studies, and to the University of Minnesota for the strength of a unified research center. Look to your own students, whose activism has been showing you what they need for more than 62 years now. There has been progress in implementing ethnic studies curricula across the nation, but, if it is to uphold the promise it has made to its students, Harvard still has a long way to go.

Images Credit: Annie Harrigan