“We go to the demonstration, and there’s six workers.”

In 2012, UNITE HERE Local 26 chief steward Ed Childs spent a summer organizing workers to protest against the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte. When it came time to demonstrate, Childs and another out-of-state organizer were dismayed by the low turnout. “We look at it like, oh God, this is a bust. But we noticed everyone else was very happy,” he said in an interview with the HPR. “They said six workers, in Charlotte, in a right-to-work state—that’s big. You got a sense of how repressive this was.”

National labor unions were demonstrating in Charlotte because the Democratic Party—which has relied on labor as one of its core constituencies since the New Deal—was hosting its national convention in North Carolina, which has been a right-to-work state since 1947. Right-to-work laws make it illegal for unions to compel new employees to join unions and pay dues in order to work.

Union advocates see these laws as a grave threat because they hinder the financial and political power of unions. In the long run, right-to-work laws endanger the ability of unions to advocate for the workers they represent, and they may endanger the very ability of the American left to organize itself.

The right-to-work question has ascended from the state to the federal level with the advent of Donald Trump, who rose to power partly on a platform of protectionism and blue-collar support, but whose subordinates and Congress alike are highly supportive of such anti-labor legislation. A federal right-to-work law has already been introduced by Republican Congressman Steve King of Iowa, and the passage of such a bill could devastate organized labor across the country.

Closing shop

If right-to-work does become the law of the land, it would be the culmination of a movement that has been gaining momentum for 70 years. Right-to-work laws trace their history to the Labor Management Relations Act of 1947, better known as the Taft-Hartley Act. The previous National Labor Relations Act of 1935 allowed for four different types of labor-management relationships. Companies could declare themselves closed shops, in which employees are required to be members of the union when they are hired; union shops, which require newly hired workers to join a union after a certain amount of time; agency shops, which allow workers to opt out of paying regular union dues if they pay a one-time fee to cover the costs of their representation; or open shops, which do not compel workers to join a union at all.

The Taft-Hartley Act made closed shops illegal nationwide and permitted states to pass laws making union and agency shops illegal. These state laws have become known as right-to-work laws, and have since been passed by 28 states, with eight of them enshrining right-to-work in their constitutions. Since 2012, six more states have passed right-to-work legislation. Earlier this year, New Hampshire defeated a right-to-work bill by a vote of 200–177, while Missouri and Kentucky successfully passed right-to-work laws.

When the open-shop model is the only legal choice, unions must rely on voluntary dues to continue operations. This forces unions to divert time and resources from litigation and collective bargaining to membership retention. As the case of Oklahoma demonstrates, this does not necessarily spell certain death for unions, but it does mean an uphill battle.

Right-to-work proposals have emerged twice in Oklahoma’s history, and have polarized the Oklahoma community—both during votes on right-to-work laws, and now, after right-to-work has been passed, as people examine the law’s impact. The debate began with a ballot initiative for its creation in 1964. Anti-right-to-work posters were hung, displaying quotes from Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr: “so called ‘right-to-work’ will rob us of our civil rights and job rights.” Introduced by a constituent, the proposal failed with 52 percent of votes against it.

But right-to-work did not end there. On September 25, 2001, Oklahomans headed to the polls to vote for another right-to-work proposal. This time, it passed with 54 percent votes for it, and was enacted just three days later. Unlike the 1964 measure, this proposal was introduced by the state legislature. While there is usually a strong partisan divide on right-to-work, with Democrats against and Republicans for, Oklahoma’s ballot measure was proposed by Democratic State Senator Dave Herbert. Following the tradition, all of the Senate Republicans voted in favor of the bill, while just 17 of 30 Democrats opposed it.

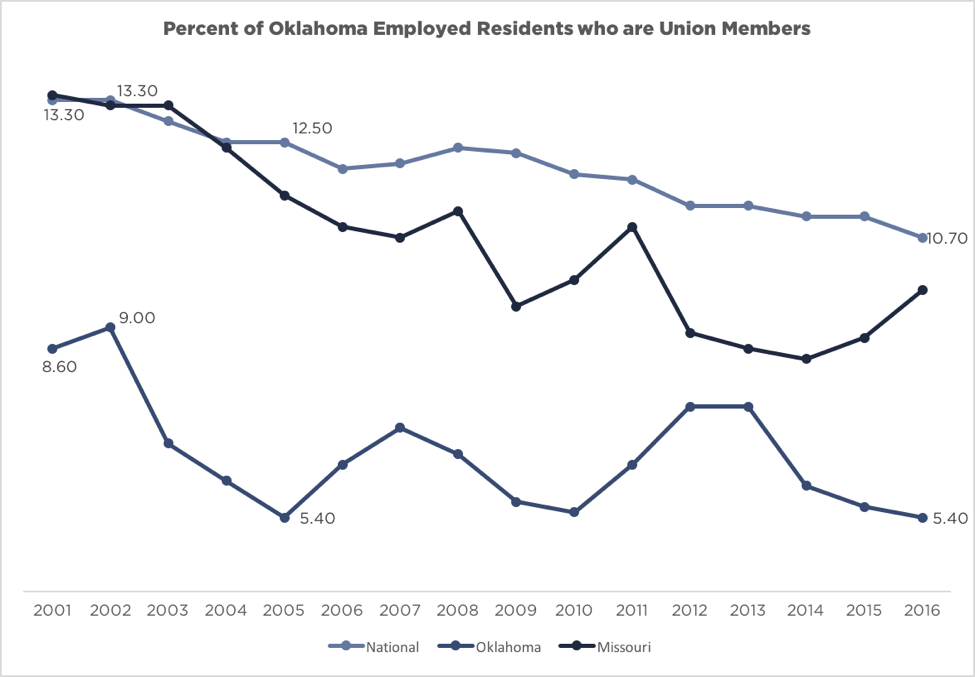

Oklahoma’s union membership took a hit after the law was passed. As the above graph shows, union membership in Oklahoma still increased in the year after the right-to-work law was passed, albeit at a slower rate, and reached a peak of 9 percent. It then sharply decreased to its lowest point of just over 5 percent in 2005. Union membership has since fluctuated, rising and falling before plummeting to 5.4 percent again in 2016. Oklahoma’s instability is a stark contrast to the national rate of union membership, which has slowly but steadily declined. In comparison, Missouri, which is geographically close to Oklahoma but only passed a right-to-work law in January 2017, has seen its union membership rate experience much less volatility than Oklahoma’.

Oklahoma’s right-to-work law has been in effect for more than 15 years, and there are various opinions on its impact on the state’s economy. The official Oklahoma State Chamber position supports right-to-work because of its purported positive effects on job creation and personal income growth. It cites statistics from the National Institute for Labor Relations Research, whose director, Stan Greer is a noted right-to-work advocate. Greer notes that the state had rapid growth in private sector compensation following the right-to-work law, which is highly unusual considering the state’s slow growth before the law was passed.

However, a study by Louisiana State University and Claremont McKenna College shows that this law had no effect on many state trends, including the unemployment rate and average wages. Another study by researchers from UC Berkeley and University of Oregon political scientist had similar findings. These latter studies come from parties with less of a direct stake in this debate, and thus it seems more likely that their findings that the right-to-work law has not significantly contributed to the state’s economy are more reliable than the state chamber and the NILRR’s statistics. The law certainly has not impacted workers in a measurably positive way, as it led to neither a decrease in unemployment nor an increase in wages.

Workers’ rights

Workers have a right to be represented by their company’s union regardless of their member status. In right-to-work states such as Oklahoma, this means that workers who do not pay dues still receive free representation in matters such as grievance disputes and wage negotiations. The expansion of right-to-work from the state to the federal level “would mean that unions everywhere would face a massive free-rider dilemma,” said Harvard professor Benjamin Sachs in an interview with the HPR. “They would be required by the duty of fair representation to represent everybody, but couldn’t charge anybody for it.”

On its own, the free-rider problem does not pose an insurmountable obstacle for unions, as the persistence of Oklahoma unions demonstrates. However, with Republicans dominating legislatures at both the state and federal levels, the assault on labor unions has no end in sight, and unions’ shrinking financial power may severely hamper their ability to fight these changes. David Madland, a senior adviser to the American Worker Project at the Center for American Progress, sees this as a fundamental problem for American society. “We are in a moment where democracy itself is vulnerable,” he said in an interview with the HPR. “We have a president who has authoritarian tendencies, and the ability to check that power is absolutely crucial. The way to do that is through organizations like unions.”

One of the common justifications for right-to-work laws presented by analysts and organizations is that these laws increase workers’ freedom of association. However, the people directly involved in this debate—workers and legislators—don’t often use these arguments. “I never heard a worker say that,” said Childs, “nor did I hear the other side say that. In Wisconsin, there was no preface except to get rid of the unions. [Governor Scott] Walker doesn’t go out making speeches saying he wants freedom for workers.”

It is difficult to see right-to-work laws as anything other than a tool for the Republican Party to hobble the power of the Democratic voting base. From January 2015 to August 2016, labor unions donated a total of $108 million to political campaigns, and almost 85 percent of it went to Democrats. “The right-to-work law and, along with it the dismantling of public-sector union rights, is understood to have political implications,” said Sachs, “to defund the Democratic Party, to undermine [its] organizational capacity.”

What could be at stake is thus not only the future of unions themselves but the Democratic Party as a whole. “Republicans make a calculation that the short-term pain is worth it because of the long-term shift in power it entails,” said Madland. The massive backlash in Wisconsin over a 2011 bill that stripped public unions of most of their bargaining rights—and the Republicans’ subsequent victory there in the 2016 election—seem to bear Madland’s point out.

Organized labor poses a challenge to Republican rule not only because of their association with the Democratic Party but also because of labor unions’ long history of standing in solidarity with other social movements. Suffragists argued for the vote in part based on a need for greater regulations in women-dominated workplaces. The 1912 Bread and Roses strike, which led to increased wages across New England, was composed of immigrant workers from over 40 countries. Civil rights leaders in the 1950s and ‘60s saw racial justice as inextricably bound up in economic justice, and when Martin Luther King, Jr. was jailed in Birmingham, it was a union leader who bailed him out.

The potential collapse of labor unions under right-to-work could easily dissolve the coalition of labor, women’s rights, and civil rights groups that has formed the political front of the American left since the Industrial Revolution. But the situation is far from hopeless. There remain legal grounds on which to challenge many individual states’ right-to-work laws, according to Sachs. “Many state right-to-work laws are overbroad,” he said. Under the Taft-Hartley act, Sachs says, “all that states should be able to prohibit is an agreement … that requires the employees to pay the equivalent of membership dues and fees. In fact, right-to-work laws go further than this, and many of them say you cannot be required to pay anything to a union at all.” In other words, illegalizing the agency-shop model, as right-to-work laws do, is in conflict with the federal statute, and may be grounds for overturning these laws.

Should a federal right-to-work law pass, however, federal and state laws would no longer be in conflict on the matter. Childs sees such a law leading to massive union unrest and demonstrations. “Even the most backwards union leader doesn’t want to see their organization dismantled,” he said. “Even among the workers who voted for Trump, there’s not one honest worker who voted for him and wants right-to-work.”

Madland sees not just workers but the American public as having a profound stake in this fight. The public, he argues, must act now against King’s proposal for a national right-to-work law. Madland suggests that the best way to prevent the law from passing is by having Americans call their representatives and ask them to vote against the bill. If the public starts now, he says, we can switch from having a “right to work” to what he calls actual “rights for workers.”

“There needs to be a broad recognition amongst the public of what’s at stake,” he said. “This is not just an attack on unions but an attack on democracy itself.”

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Equality Michigan Copyright BY-SA 3.0