In an interview with the Harvard Crimson last year, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger mentioned something unique about the Kennedy administration: it was the first to heavily utilize college professors. Kissinger said, “it was only in the Kennedy administration in the sixties that an organic relationship was established between the White House and Harvard… [that] has continued not so much between Harvard and the White House, but between the academic world and the White House.”

This mindset of professors, not only as educators but also as policymakers, has pervaded our government since the 1960s. And why shouldn’t it? While some argue that so-called “technocrats” are incapable of directing nations through troubled waters, few oppose the idea of having informed and scholarly advisers guiding our leaders.

There is a readily fluid relationship between “governing” and “campaigning.” During the 2008 presidential election, John McCain’s advisors included professors from Stanford, Columbia Business School, Vanderbilt, and Harvard among many other institutions. Barack Obama’s advisors notably included Lawrence Summers and Jeffrey Liebman, two big-name Harvard professors who left the “Kremlin on the Charles” to advise the then-Senator. Now, Alan Krueger, a professor at Princeton, is the administration’s top economic advisor

However, what might once have been considered mere policy and campaign advice has become something new, as professors have turned into political surrogates.

A Real Problem

Harvard historian Niall Ferguson is well known for his conservative political opinions, especially concerning economics. His rows with staunch liberal Paul Krugman are as entertaining as they are informative, and his lectures are spectacular. In his class “International Financial History,” he switches rapidly between discussions of gold bullion and credit default swaps to the origins of monopolies on printing money and ancient banking in Sumeria.

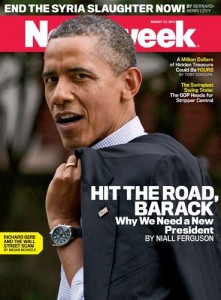

The August 27, 2012, Newsweek issue featured an opinion piece by Professor Niall Ferguson entitled, “Obama’s Gotta Go”

While beloved in the classroom, Ferguson recently created a firestorm of controversy with his Newsweek cover story, “Obama’s Gotta Go,” an economic analysis of President Obama’s campaign promises and rhetorical points. But, soon after its publication, Ferguson faced a slew of responses that challenged his facts and accused him of manipulating the truth. A close examination is telling: for instance, Ferguson uses employment numbers from January 2008 as reference points, even though Obama was inaugurated a whole year afterwards. Likewise, he writes that the expenses associated with Obamacare incur a “net cost” of $1.2 trillion but fails to mentions a CBO report stating that the accompanying cost saving will render it debt-neutral. For a few short hours on the blogosphere, a legion of fact-checkers produced a complete set of analyses encompassing many more factual errors than what was just mentioned.

However, Ferguson is not the only Harvard professor to become entangled in dubious factual assertions. This election has seen a slew of professors jumping to aid candidates from both parties. Harvard’s experts on history, economics, and political science are now slinging mud as easily as they once slammed each other in peer-reviewed quarterly journals.

Gregory Mankiw, professor of Harvard’s largest course, “Introduction to Economics,” has long been involved in Republican policymaking, and formerly served as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers for George W. Bush. Mankiw, now an economic advisor for Romney and a regular columnist for the New York Times, is one of the strongest voices for center-right economics in America today.

In August, Mankiw co-authored a policy briefing with others on Romney’s economic advising team. We should not be surprised by its conservative slant, as Mankiw’s job is to present a coherent academic argument for Romney’s economic goals. What should concern us though are the briefing’s misrepresentations and omissions of economic research. As the Washington Post noted, the briefing left out favorable economic studies on the Cash for Clunkers program. Beyond that, the briefing ignored most studies that credit the stimulus with halting the economic downturn. Overall, the three professors that authored the paper, Mankiw chiefly among them, seemed to have traded their academic laurels in for partisan pompoms.

In August, Mankiw co-authored a policy briefing with others on Romney’s economic advising team. We should not be surprised by its conservative slant, as Mankiw’s job is to present a coherent academic argument for Romney’s economic goals. What should concern us though are the briefing’s misrepresentations and omissions of economic research. As the Washington Post noted, the briefing left out favorable economic studies on the Cash for Clunkers program. Beyond that, the briefing ignored most studies that credit the stimulus with halting the economic downturn. Overall, the three professors that authored the paper, Mankiw chiefly among them, seemed to have traded their academic laurels in for partisan pompoms.

The politics of professorship extend beyond the role of “advisor” though. Many political juggernauts from the past few decades first began by leading classrooms. Presidents Obama and Clinton taught law, as did Massachusetts Senate candidate Elizabeth Warren. Newt Gingrich was a history professor before entering Congress, and Robert Reich, Labor Secretary under Clinton and former candidate for the Massachusetts governorship, teaches economics at U.C. Berkeley.

I am certain that these professors believed that their personal ideologies had no place in any college curriculum. But, should we be concerned when partisan candidates and their partisan advisors use rhetoric that misrepresents the truth? This is debatable, because politics primarily concerns candidate narratives and messaging. What is instead worrisome about professors, Republican and Democrat alike, is not that they inform politicians and the general public from their perches in the ivory towers of academia, aloof and distant from the “real world.” Rather, it appears that the exact opposite is taking place: our professors have abandoned their sacred role as the unbiased arbiters of fact and fiction in favor of much more partisan roles.

A Brief History

I recently spoke with John Thelin, a professor of the history of academia and public policy and the University of Kentucky, and author of an article on Mitt Romney’s time at Harvard.

According to Thelin, our view of professors today originates in the German universities of the 19th century. A new focus on research, humanities, and the interconnectedness of disparate fields had the auxiliary effect of promoting professors as the unique holders of knowledge. “If you read into German universities in the 19th century, where the tradition of the grand lecturer came about, [you’ll see that] there’s always been some temptation… where professors begin to use the bully pulpit.” Fast forwarding to today, we observe that professors use their positions not only to educate their students, but also as “pulpits” to advance personal beliefs.

However, this inherently might not be problematic. Students know when they are being lied to and when they are only hearing one side of the story. One could even argue that students are self-policing; for instance, some biology students have insisted on hearing about both creationism and the theory of evolution.

A problem arises though when confronting the other role that our professors play as educators for the public. One of the biggest differences brought on by the Internet, Thelin said, was the transformation in the target audience for academics. “If a professor who’s an expert is talking to or writing for a national audience, it’s a very different responsibility than leading a seminar or leading a lecture.” What happens when a discussion moves from the small academic environment of university campuses to the open, public arena of political dialogue? Cordial debate, subtle details, and intensely considered arguments may fall by the wayside in favor of harsh rhetoric, used as blunt weapons to degrade the opposing side.

This may explain Mankiw and Ferguson’s recent transgressions. Indeed, some professors choose to flex their academic expertise to play hardball on the national stage, forgetting or even ignoring the reality that subtle points of economics or history are most likely lost when taken in short sound bytes, second-hand conversations, and bold headlines that read, “Obama’s Gotta Go.”

Moving Forward

Louis Menand, an English professor at Harvard, was once asked, “Who is your audience?” He replied simply, “I have to write… in a way that appreciates that… [the reader] is probably a very well-educated, smart person that at the same time doesn’t know anything, effectively, about what I’m writing.” Simply put, intellectual curiosity is far more important than formal training in any given topic.

The market for information has risen with the democratization of journalism on the web. This new audience has an intense thirst for knowledge, reflected by the success of platforms like BigThink, TED Talks, iTunesU, Academic Earth, and MIT OpenCourseware. People are beginning to realize the true value of having the entire academic world at their fingertips.

Meanwhile, our professors must recognize this new academic climate. Millions of people are supremely thirsty for knowledge, but may not have substantive backgrounds in any given field, whether economics, history, politics, or something else. Professors have the sacred responsibility of bringing these new readers into the debate, not assuming that they will forever be susceptible to partisan pandering, lax fact checking, and half-truths.

This does not mean that professors should stoop to the lowest common denominator of writing just to reach the largest audience. Nor does it mean they should retreat back into academia, having failed to raise our national discourse into something more productive. But, they must take the time to explain one’s field and sow the seeds for a new cadre of informed readers, both inside and out of the classroom. Professors, give us time, guidance, and most importantly, all of the information. We’re curious.

What used to be cloistered academic discussions amongst peers with PhDs is now broadcast and splashed on front pages across the world. If fundamentally transformative educators rise to the occasion, they will recognize that their arguments, discussions, and debates can truly be tools for bettering our world and for getting more people involved in solving the challenges that face us. But, professors must realize that they cannot sink to our current level of discourse; they must lift us up to theirs.