The live-action “Mulan” movie is no stranger to criticism. #BoycottMulan began trending in August 2019, more than a year before the live-action “Mulan” release. Protestors lobbied against the movie because Chinese star Liu Yifei, the actress who played Mulan, reposted a pro-Hong Kong police comment during the democracy demonstrations last year. This year, much of the controversy surrounding the live-action “Mulan” centers around how Disney filmed parts of the live-action “Mulan” in collaboration with the Chinese Communist Party of Xinjiang that is directly responsible for committing cultural genocide against Uighur Muslims.

In light of these issues, the cultural and patriarchal missteps of the movie’s plot may seem secondary. However, even if Disney had filmed the movie without affirming cultural genocide, the live-action “Mulan” would still be incredibly problematic for women and Chinese culture.

Aesthetically, the live-action “Mulan” resembles a Wuxia (武俠) story, a Chinese martial arts heroes movie, and it more closely adheres to that archetype of film than the standard “Disney Brand.” At face value, it appears as if the live-action “Mulan” is trying to be more authentically Chinese, using an Asian art form. However, looking closer, the live-action “Mulan” exposes itself as an over-orientalized Western perspective on Chinese culture, not a genuinely Chinese story.

The live-action “Mulan” is so devoted to filial piety and Mulan learning her place in society that the movie misses the core of Chinese stories, including the Wuxia movies it aesthetically resembles: hard work. In contrast, although Disney’s animated “Mulan” was also quite a Western story, it manages to capture the essence of the original “Ballad of Mulan” by centering Mulan’s character around the core Chinese values of effort and perseverance.

Disney may have made the changes from the animated to the live-action movie to more closely adhere to the original Chinese poem, but a cursory look at the new adaptation shows this cannot be the case. In the “Ballad of Mulan,” Mulan begins at a loom as a typical woman of her time, unlike the live-action prodigy Mulan. The poem’s Mulan works hard to fight alongside her male counterparts and wins accolades and promotions through her efforts, like in the animated “Mulan.”

The animated Mulan’s greatest strength is that she solves her problems, even overcoming the men in her story, through her intelligence and work ethic. Everyone remembers the scene where Mulan becomes the first person among her training group of men to successfully climb to the top of the pole using the weights instead of being dragged down by them. This character development builds to her defeat of the main villain of the movie, Shan Yu. Mulan applies her cultivated skills and intelligence to take control of Shan Yu’s sword using her fan, pin him in place, and knock him off a roof with a firework, saving all of China.

The animated Mulan’s story is fundamentally about gender roles as well. Mulan struggles to see herself as a potential bride at the beginning of the movie during the song “Honor to Us All.” Mulan also misunderstands how to present masculinity when she first walks into camp, staggering around and hitting men to greet them.

Still, by the end of the movie, Mulan and her fellow soldiers learn to embrace femininity as a weapon, infiltrating the palace by dressing as women instead of ramming their way through the main door. Mulan can fight as well as a man, and she does, but she ultimately defeats Shan Yu by using her fan and her intelligence, not her masculine strengths. The resolution of her story is so compelling because it resonates with everyone who has struggled to fit into their own cultural conventions. In contrast, the live-action Mulan never challenges the status quo or re-evaluates how she lives her life.

Instead, the live-action Mulan is a prodigy, gifted with superhuman abilities because she has “strong chi.” Chi (气) is a traditional Chinese concept, the life energy that “fuels” all beings, like breath or blood. Chinese acupuncture is based on the flow of chi, and chi often appears in Chinese stories as a major element. However, the new Mulan fundamentally mischaracterizes chi to the point where most Chinese people are simply confused by this “cultural” reference. Chi is not selective like the force from Star Wars; everyone has chi. In other Wuxia movies, characters can cultivate chi through hard work, and it would have been so easy for the filmmakers to focus on this version of chi, to value hard work over natural ability. But instead, because of her superpowers, the live-action Mulan can just kick aside her problems with her superhuman strength.

Additionally, the live-action Mulan does not come in conflict with her society’s gender roles; her actions are dictated by “knowing her place.” She never faces any backlash for revealing herself as a woman either, because she has these superhuman abilities. The men in her story accept her because she is strong in a masculine way, yet she still subscribes to her societally determined role. She chooses to fight as a woman because she never has to struggle against the constraints of her gender, and she never needs to use her resourcefulness to overcome challenges in her story.

There are two other new characters in the story whose arcs reinforce the patriarchy within the live-action movie: Mulan’s sister and the Witch. Mulan’s sister is an ordinary girl for her time, not gifted with superpowers like her sister. In a version of the movie actually focused on empowering women, Mulan’s sister might have been inspired by Mulan to dictate her own life choices. However, when Mulan returns home, her sister runs up to her, excitedly proclaiming that she “is matched” for marriage. Mulan’s sister is not special, and this subplot, which is unrelated to the main story, just serves to illustrate that normal women, unlike prodigy Mulan, must stay confined to their prescribed societal roles.

The other character that reinforces the patriarchy does so in the opposite way, demonstrating how a woman overstepping “her place” must be punished. The Witch is meant to be a dramatic foil to Mulan, another woman gifted with supernatural abilities who dares to present herself as a warrior. The character of the Witch has more power than any other character in the movie, single-handedly taking down fortifications and infiltrating the imperial palace. However, she works with autonomy and is only barely willing to stay subservient to the Rouran warlords she works with. Under this movie’s premise, the Witch has to face retribution by dying for using her abilities outside of the status quo. It is difficult to imagine a reason for either of these subplots beyond enforcing a hyper-orientalist perception of Chinese attitudes towards society and gender roles.

Chinese people often are portrayed in Western media as confined by the status quo, subscribing to “Confucian values” and patriarchal structures. Chinese women especially are shown as subservient and unwilling to challenge their stations. The live-action Mulan is given a place in society, a place that she never needs to challenge, unlike the other Mulans before her. She and the women around her either fall directly into this Chinese stereotype or are punished by the movie for deviating from it. Chinese people have nuance, as all people do, and it is painfully evident that there were no Chinese writers behind the scenes because the live-action movie lacks this nuance in its portrayal of gender roles and Chinese society.

The animated Mulan is a feminist hero because she carves out her place, negotiating her gender on her own terms. Disney’s live-action “Mulan” could have been an amazing opportunity to bring Mulan’s story of empowerment to a new generation of young women and represent genuine Chinese culture, but instead, we got this movie.

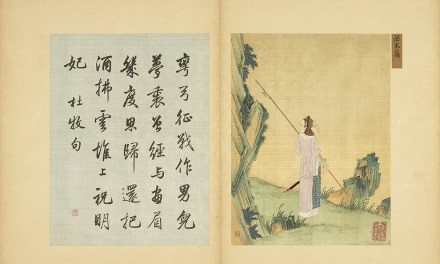

Image Credit: He Dazi (赫達資) was identified as the painter. Liang Shizheng (梁詩正) wrote the accompanying text in 1738. The text is from lines of older poetry, directly or indirectly related to events depicted in the paintings. The original authors of the poetry are not given., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons