I went to see Moonlight alone, one weekend during reading period. The roads were iced and my hair was undone but I made a spontaneous decision to catch the 2:15 showing—I arrived at 2:30, sweating, opening credits rolling: every n*gga is a staaaaar…

It was December and To Pimp a Butterfly had recently transformed me. I had started listening to rap only a few months before; I was a first-generation American who refuses to say the n-word; I was a shy girl from a safe, pretty suburb of New York who had read multiple reviews about Moonlight which hailed the film as a monumental portrayal of LGBTQ+ intersectionality. There is nothing in Moonlight that is supposed to remind me of my own life, save for the fact that, like the protagonist Chiron, I am black and queer and grew up trying to escape labels.

These were not things I thought about while watching the film. I was too busy crying in the darkness, wiping my face with my sleeve, trying very hard to sniffle silently—overwhelmed by Chiron’s pain, his trauma and silence. By the third part of the film, my red, swollen eyes were aching so badly I had to close them. And then when Chiron, grown up and drug dealing, appeared on the screen, I heard an elderly woman behind me exclaim, irritably, “I don’t want to see this part!”

But the beauty is that Moonlight shows you an entire life, without saying anything about the fact that it is a traumatic life, and a very, very culturally coded one. Drug dealing is a legitimized occupation, imprisonment is commonplace, and aggressive masculinity is an established survival skill. Even when I found out that Juan, Chiron’s father figure, is the man selling crack to Chiron’s mother, I loved him because I knew him as a father figure. And even when Chiron grows up, I loved him because I knew Chiron, from the silently suffering six-year old to the drug dealer performing black “manhood,” all versions of him struggling to survive in an unjust world.

The beauty of Moonlight is that it is more than an LGBTQ+ film. It is a film whose pain and beauty rely on elements beyond queerness and intersectionality, and shapes a culture and history into the backdrop of its narrative; Moonlight is Chiron against the crack epidemic, the rise of hustling, the homophobia of black culture and the expectation of failure. It pulls you into a world that encapsulates, entirely, a black experience.

For me, drying my eyes with my fingers on the sidelines, Moonlight was a triumph in the representation of black diversity in America. The combination of blackness and queerness onscreen was something I had never seen before, but I had also never seen an experience so dictated by race-based disadvantage. The others in the theater that day, most of them nonblack, probably had never seen a film like this either, and perhaps they didn’t make that connection. But as we filed out into the blinding brightness of the hallway, I realized that anyone looking at me—dark-skinned, puffy-eyed, ironic rainbow bracelets—would have assumed that when I was watching Moonlight, I cried because I was seeing myself on the screen. But in fact Chiron did not remind me of myself at all. We inhabited two completely separate worlds, and for two hours I stepped into his, and for hours after that I could barely speak, because silence was what we had in common; apart from that, nothing else.

I returned to campus as soon as the film had ended, dazed, thinking deeply about the differences between that experience and my own, reflecting on my privilege. I could have thought about anything else—how I learned to smother my emotions in childhood, how I sobbed when kids called me a dyke in school, how I started to find pain in speaking—but the thing is that before anything else, Moonlight, for me, is a black film. The fact that most of its reviewers choose to highlight its queerness above other important elements demonstrates an ignorance of intersectional struggle that causes problems between movements. I will always be black before I am female. I will always be black before I am queer. My race is the mould for all of these aspects of my identity, and to misunderstand this is to commit an erasure of personhood. I cried because I have watched many queer films, many coming of age films, and many black films, but never have I seen a film so rooted in contemporary and cultural blackness. There is, in Moonlight, both the perpetuation and annihilation of stereotypes—for example, Chiron’s arrest, and the reasons behind his arrest. The whole concept felt very much like navigating America in a black body, all these signs woven into my skin, so many expectations of disgrace and failure.

It also felt a lot like To Pimp A Butterfly come to life, a gritty, raw depiction taken from the spectrum of black America that most people find themselves unable to handle. Like the woman in the theater, people of this century protest against these kinds of realities, cover their eyes, cry only over movies that emphasize a separation between America’s past and America today. When Moonlight won Best Picture at the Academy Awards last week, it felt like for once the nation was moving its hands away from its eyes and finally coming closer to us, looking, and maybe listening.

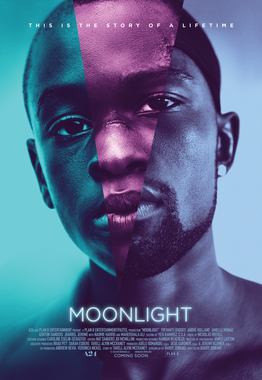

Image Credit: A24