For the past four years, the Harvard College Israel Trek, sponsored by Harvard Hillel, has taken 50 Harvard students to Israel and the occupied Palestinian territories over spring break to travel throughout the region and learn about its complex history. This year, we packed our bags and joined the trek for what proved to be nine days of challenging discourse and remarkable adventure.

Upon returning to Harvard, we were eager to share what we saw, to provide fresh insight into the deeply politicized narrative of this age-old conflict through the medium we knew best: our writing. Words failed us, however, as we realized that we had even more questions than we had before departing: Is true democracy possible in a nation bound by its religious identity? Is our definition of democracy––as shaped, unavoidably, by our experience as citizens of the United States––really the standard of comparison? Is my definition of democracy outdated? After so many years of negotiation, is a lasting resolution even possible? Is peace possible?

If anything, we learned that the conflict, in all its complexity, is not a dichotomy of two “sides” from which we could choose. The Israel-Palestine conflict is distinctly personal, and deeply intertwined with the identities of Israelis and Palestinians today. The pain and tragedy that color the experience of the region’s residents is difficult to comprehend from the United States, so detached from the conflict. The question so often posed—“Are you pro-Israel or pro-Palestine?”—fails to acknowledge the deep nuances that complicate a conflict involving real people, each with their own experiences, politics, and pain. It may be easy to pick a side and to label the other “terrorist” or “apartheid” from a thousand miles away, but standing on the ancient soil of a land so vibrant yet so ruinously tormented, looking into the eyes of an individual who has lost someone—father, sister, husband, friend—to the carnage, this sort of Manichaean clarity dissipates.

Toward the end of our trip, in a small moshav called Nahalal some ten miles outside of Nazareth, we sat down with Meir Shalev, a prominent Israeli author and columnist. He told us several stories of his early years in Israel, a break from the political discussions with members of the Knesset, former Supreme Court justices, and activists during preceding days. One story in particular sits with us still. He told us of a young woman whom he had written of some 40 years ago, an American lover whom he had lost touch with over decades and borders. She reconnected with him recently, only to contest his telling of their story; she claimed that the events he portrayed misrepresented the facts entirely. He turned to us, a mischievous smile expanding across his face, and explained that there are many ways to tell a single story. Every eye notices different detail, and every ear picks up a different sound. What unites these many narratives is not the way the story is told, nor the significance they have to any individual—it is the facts, the undisputable quantifications, that serve as the basis from which stories can be told.

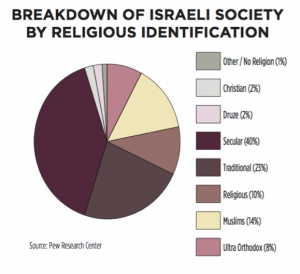

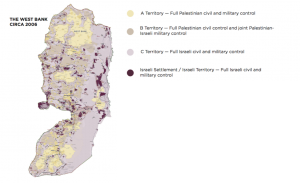

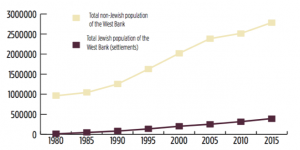

In the following images, we present to you a breakdown of the region’s diplomatic, military, and geographic histories. These are some of the few events that can be agreed upon by all parties of the conflict. We seek not to tell you our story, nor that of any individual; our goal is to give you the framework necessary to ask questions of your own, and perhaps, to craft your own story. The Israel-Palestine conflict is merely one of many possible narratives, each as honest as the next. If we are to one day find peace in the region, we must begin by acknowledging the many stories that form its identity.

Image Credit: Russell Reed/Harvard Political Review