Before he became the longest-tenured heavyweight champion of the world and, according to many, the first African American to achieve the status of national hero, Joe Louis was an average 15-year-old teenager growing up on the east side of Detroit. In the midst of the Great Depression, Louis found himself—like many of his peers—seeking solace in gang membership, a common theme in his neighborhood. Louis’s mother sought to guide him away from his more violent urges by paying him a daily stipend of 50 cents—intended to fund Louis’s career as a violinist. Louis gladly accepted the offer, although he did not take up the violin. Instead, he used the money to fund his trips to the gym to study the “sweet science” of boxing. Twenty years later, Louis found himself in a cohort with boxing’s most formidable champions.

While Louis overcame his childhood struggles through his devotion to boxing, the reality for most teenagers in East Detroit is much starker. Over the past four decades, many children within the impoverished neighborhoods of urban Detroit have faced the same troubling conditions Louis once battled. But without the same guidance that Louis’s mother offered, many of these youths struggle to escape the vicious cycle of poverty and violence which has plagued the streets of Detroit for decades. In Louis’s time, the Great Depression hammered Detroit’s auto industry, forcing thousands of factory-working families into socioeconomic turmoil. Today, thanks in part to an auto industry less than a decade removed from bankruptcy, Detroit’s youth face a city with the nation’s highest violent crime rate and one of the most dysfunctional public school systems in the country. For over a century, the question of how to rebuild the city of Detroit has persisted without resolve. But today, a spirit of hope endures within those who will determine the city’s future: its youth.

The Monument to Joe Louis, better known as “The Fist,” in downtown Detroit.

Instead of turning towards gangs and crime for their escape as so many have in the past, many of Detroit’s teenagers are now exploring the path Louis once championed. In many ways, these children’s’ turnaround embodies a much greater movement emerging in Detroit. Local leaders from various backgrounds are transforming the city through education, innovation, and revitalization. Still, a unique aura of excitement surrounds the city’s youngest generations as local leaders prepare them to construct a prosperous future for Detroit.

Education’s Emergence

Sarah Sorenson coordinates the academic side of the Downtown Boxing Gym Youth Program of Detroit, an organization which has given Detroit’s adolescents the chance to develop a sense of commitment through the sport of boxing. There’s only one caveat: the books come first. “Our goal is for students, at the time they graduate from high school, to be ready and to be adequately prepared to choose whatever type of college path or career path that they want to,” Sorenson told the HPR. By offering everything from personal tutoring to college advising, the DBG is empowering teenagers with the education they will need to succeed in the 21st century economy. For these kids, the DBG is far more than just a tutoring program and a boxing gym. “It feels like family when they come to the gym,” Sorenson said, “and they know that’s a place where there are people who care about them and will help them do whatever it is they are trying to do.”

Sorenson, a graduate of the University of Michigan, is part of a growing number of in-state graduates who are joining the movement to revitalize the city of Detroit. Gabe Karp, another University of Michigan alum, has played a large role in the city’s economic restoration. As a partner at Detroit Venture Partners, Karp has helped coordinate the remarkable influx of talent into Detroit in recent years. Instead of finding work in coastal cities as they have over the past few decades, Karp says, Michigan’s college graduates are now choosing to work in Detroit because they want to be part of the city’s revitalization.

According to Karp, Detroit is already prepared to contend with some of the nation’s most established economic powerhouses—and is far less dependent on the shaky foundations of the auto industry. When Karp first joined a tech startup in Detroit in 2004, the city’s tech scene was desolate. But today, Detroit is a thriving tech city capable of going toe-to-toe with the strongest tech hubs in the country. Karp, who has experience with the tech scenes in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, told the HPR that Detroit’s tech talent “is as good as tech talent anywhere in the world.”

What Karp has found most remarkable about Detroit is not the city’s impressive economic diversity, but Detroiters’ desire to lend a hand in the city’s effort to rebuild. “Thirty years from now, I’ll be able to talk to my children and my grandchildren and say I was part of that,” Karp said. “I was part of that movement.”

This sense of community has ignited a flame of excitement even within well-tenured Detroiters, who are more than familiar with the crushing disappointments of the city’s past attempts to rebuild. Ron Fournier, a native Detroiter and editor and publisher* of Crain’s Detroit Business, recently made the decision to come home to Detroit to cover the city’s revitalization. Fournier spoke to the HPR on a football Sunday outside of a Detroit bar. “After just two weeks of living here it’s clear that for the first time in my lifetime the political and business communities are working together to try to help Detroit be reborn and make it be reinvented for the next hundred years.”

Overcoming Racial Inequality

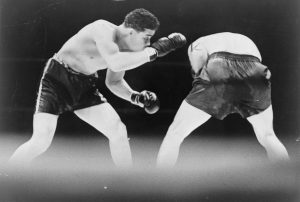

In the past, Detroit’s most iconic figures have often been defined by their struggles against racial inequality. Before Louis claimed his historic victory in 1938 over the Nazi regime’s Max Schmeling, he had to go toe-to-toe with fierce racism in his own country. In fact, had his family not been driven out of their home in southern Alabama by the Ku Klux Klan, Louis may have never found a home in a local recreation center on the east side of Detroit.

Louis (left) searches for an opening in his 1936 bout against the Nazi regime’s Schmeling (right).

It’s been nearly 100 years since Louis’s triumph, but the issue of racial inequality is still highly visible in Detroit. Leslie Andrews, the Director of Community Relations and Corporate Philanthropy for the Detroit company Rock Ventures, told the HPR that “there’s always the natural things that continue to exist.” As a lifelong resident who describes herself as “hopelessly in love” with Detroit, Andrews believes the process of defeating the racial boundaries in Detroit will be a long one.

Looking forward, Andrews believes inclusion is the key to achieving racial equality in Detroit. In Detroit, Andrews added, “everyone is not equally connected to everything that’s going on.” Andrews has devoted herself to convincing Detroiters to do what’s “within the grasp of their capabilities and responsibilities as a lifelong resident,” rather than focus on the recent wave of external involvement within the city. Andrews argues that Detroit’s revitalization rests on Detroiters “not only doing what they can, but having what they can do, be valued … and be part of a larger legacy.”

If Detroit is to truly move forward, it will take more than individuals like Andrews to sacrifice themselves for the future of the larger community. Edward Dean, a lifelong Detroit resident, understands the magnitude of the social movement needed to rebuild Detroit. Seven years ago, in the midst of the city’s economic collapse, Dean founded “The Avengers,” a youth mentoring organization that has become deeply embedded within the Detroit community. “[Avengers] actually started with a kid coming to me saying ‘Mr. Dean, you should do a program for us because there’s nothing to do for us in our neighborhood,’” Dean told the HPR. He sees his role in Detroit’s comeback as teaching children the importance of their role in Detroit’s future. Dean understands that while he cannot rebuild the city on his own, he can empower the next generation of Detroit. By giving children the skills and knowledge to one day become entrepreneurs and politicians, Dean aims “to teach them how to make a difference without violence. Grab the books and read—find out how to get in office and make a change. Come back into the community and make a difference in your community instead of finally getting a good job and leaving your city.” As Dean asks his mentees, “Who’s going to take care of the other local kids that are still here?”

Just like his fellow lifelong residents, Dean understands that the revitalization of Detroit won’t come swiftly. Fournier, for one, knows all too well to remain cautious about the prospects of a citywide comeback: “There’s no guarantee that it’s going to work; it’s not going to be a clear and even path to success.” When asked how the city could regain its former glory, Fournier responded: “[Detroit] was never as glorious as a lot of people remember it … it was glorious for a percentage of society but, for example, for African Americans or people of color it was not a glorious city.”

As the gears of social change in Detroit turn slowly, it is often hard to see true progress being made—but those who’ve been in Detroit longest have already seen the subtle signs of great change. For Dean, it’s a former member of the Avengers program returning to coach a youth basketball team. For others like Sorenson, it’s former members of the Downtown Boxing Gym returning to the gym to work with kids after being years removed from the program. And on a Sunday afternoon outside of a Detroit bar filled with “young and old, black and white and brown coming together to root for the same team,” Fournier couldn’t help but express his excitement for the city’s diverse future.

It is with a spirit of innovation, community, and hope that Detroit sculpted itself into one of America’s strongest cities—and it is at the loss of these ingredients that Detroit fell into the depths of America’s weakest. Yet, as Detroit kneels in the ring of America’s greatest cities—with bruised ego, bloodied face, and callused hands—there prevails a flicker of hope waiting to re-ignite the Motor City. It’s been over two hundred years since the city’s motto was cemented in its legacy—but its truth is more apparent today than ever before: Speramus meliora; resurget cineribus: “We hope for better things; it will arise from the ashes.”

Image Credits: Wikimedia Commons / Zirotti (Spirit of Detroit), Flickr / Alexander Day (Monument to Joe Louis), Library of Congress / New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection (Louis v. Schmeling, 1936)

*Correction: April 5th, 2017, 6:40PM—A previous version of this article incorrectly reported Mr. Fournier’s position with Crain’s Detroit. Mr. Fournier is currently an editor and publisher of the publication.