As part of its rebuilding efforts, the Russian military recently made use of a new sort of psychological weaponry. Frontline Syrian rebels received demoralizing text messages, broadcasted by Russian military personnel, detailing the income, offshore back accounts, and holiday trips of their commanders. On the Crimean front, these text messages addressed Ukrainian soldiers by name, with personal references to their wives and children in Kiev.

On the surface, the latest addition to Russia’s arsenal represents just one part of its rebirth as a military power. With an extensive reformation of its conventional and cyber capabilities, Russia has reasserted itself as a challenger to U.S. control in Eastern Europe and the Middle East.

But Russia is just one of many challengers to U.S. hegemony sprouting across the world. With an emerging economy and military, China continues to challenge longstanding notions of dominant U.S. influence in both Southeast Asia and Africa. Even in America’s backyard, Brazil has emerged as a regional hegemon capable of resisting U.S. economic influence. The rise of these powers, and the subsequently complex world order to come, has stoked worries of “chaos” on the world stage.

Fears of instability also stem from the advent of the internet, which has expanded the cast of powers on the world stage. While the United States may retain control of the flow of goods through international waters, the free flow of information through the internet, beyond American purview, has diffused information and power to many non-state actors. Apple, for example, boasts a net worth of $710 billion, which would rank 19th on the world’s GDP rankings. The New York City area claims a Gross Metropolitan Product of $1.66 trillion, which would rank tenth on that list—ahead of Canada, South Korea, and Russia. Technology’s ability to empower these non-state actors, from terrorist organizations like Al-Qaeda, to international corporations like Apple, and international trading centers like New York City, has sparked fears of a chaotic world order in which a vast number of players with differing interests will inevitably lead to friction and conflict.

However, these fears of multipolarity—a disorderly world in which power rests in the hands of many actors—fail to recognize the United States’ unique place as the world’s premier power. Not only does America boast the world’s largest economy and military, but also the world’s most extensive network of economic and military partnerships. While the rise of regional powers and non-state actors will undermine the United States’ ability to unabashedly impose its foreign policy will, the United States’ role as a truly global leader appears secure for the foreseeable future.

Unraveling Unipolarity

In response to the deceleration of U.S. growth, the rise of China, Russia’s military resurrection, and the development of young powers like India and Brazil, many have pronounced the end of American unipolarity—the concentration of world power into the hands of the United States—dead after a short reign.

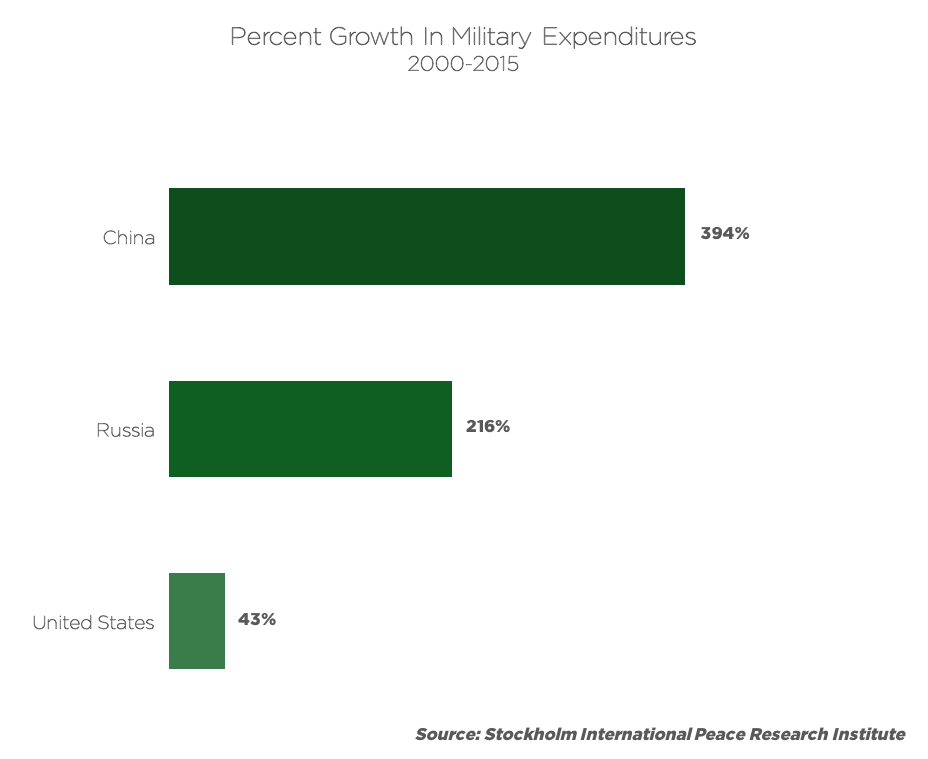

The rapid growth of multiple military powers in the eastern hemisphere lends credence to theories of unipolarity’s demise. For example, between 2000 and 2015, Russian military spending grew more than five times as quickly as American military spending. In that same period, the growth of Chinese military spending outpaced U.S. growth by more than nine-fold. Advocates of the multipolarity theory cite America’s failure to maintain stability in the Middle East as further evidence of its military decline.

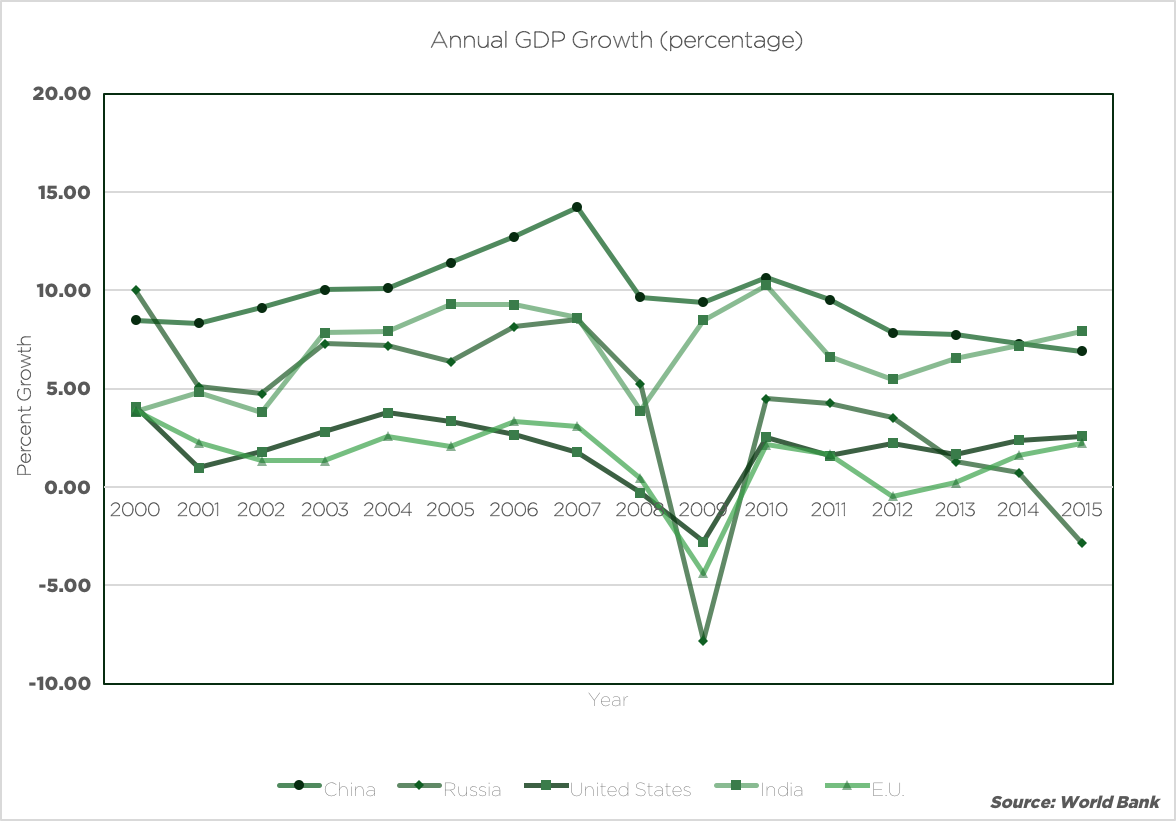

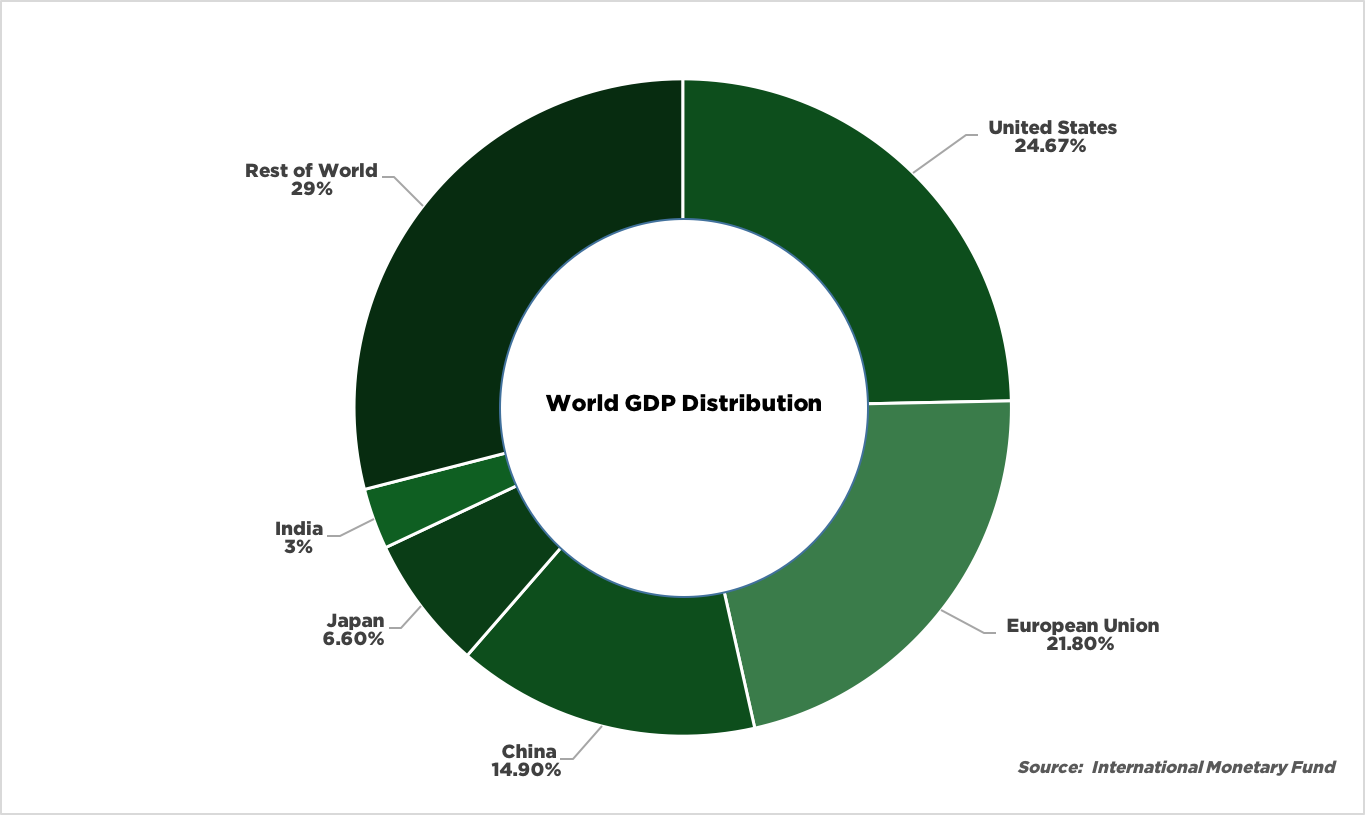

Economically, the same argument can be made. China now boasts a rapidly expanding 14.9 percent share of the world’s economy. While U.S. GDP growth has stagnated at three percent of real GDP per year, China and India claim respective annual growth rates of seven and eight percent.

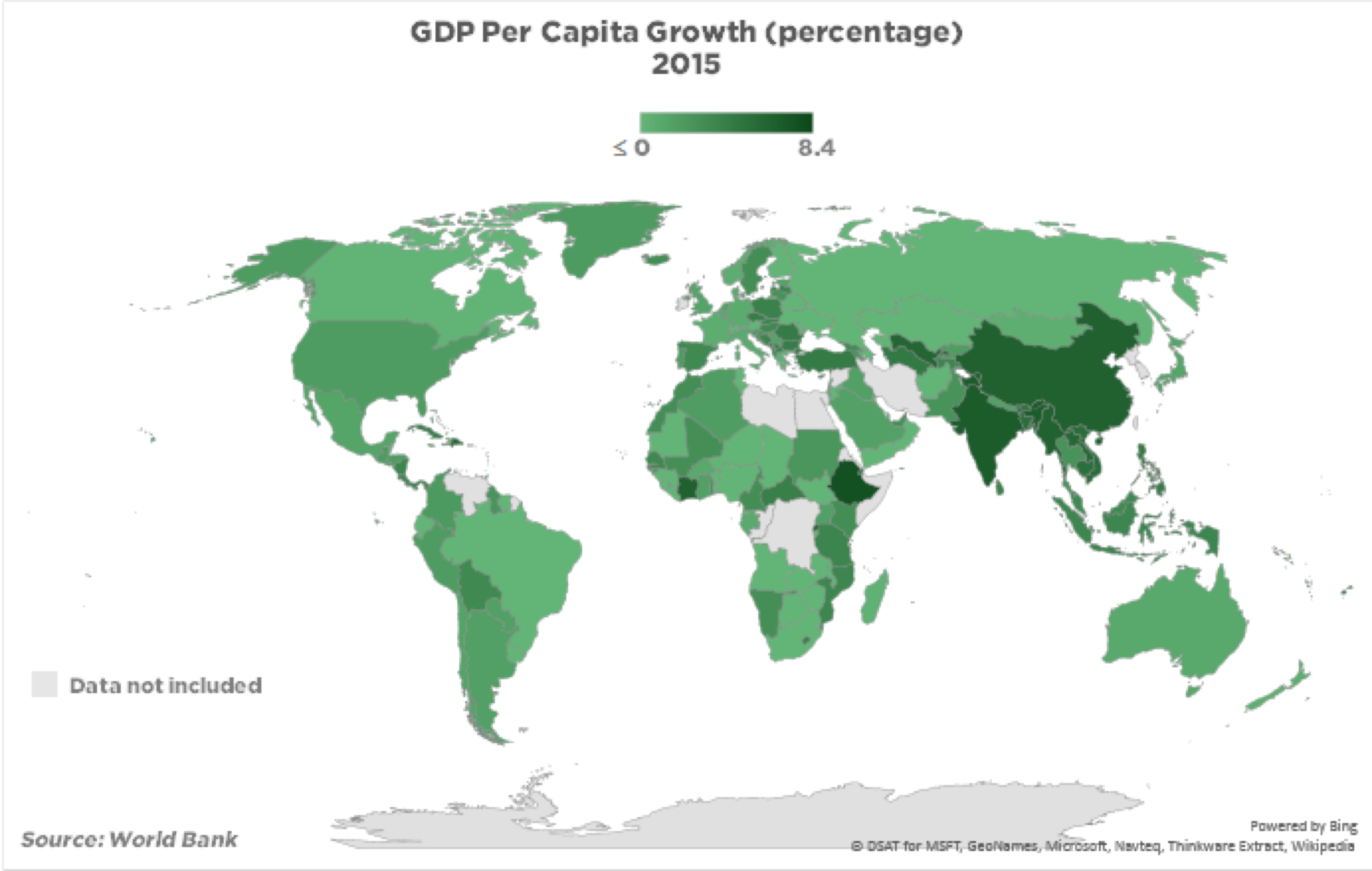

Perhaps the most telling indicator of the United States’ economic deceleration is its annual growth in GDP per capita—which measures how quickly a country’s economy is growing. As shown in the figure below, the United States remains on the lower end of economic growth (less than one percent), while actors in South America, Eastern Africa, and Southeast Asia continue to grow at rapid rates of up to 8.4 percent.

The increasing ability of regional leaders to resist America’s foreign policy impositions affirms these apparent power expansions. The United States has required the assistance of European nations in sanctioning states like Iran and Zimbabwe, who have demonstrated resilience in the face of U.S. demands for reform. Until recent Chinese sanctions, North Korea also proved capable of resisting U.S. pressure with the help of Chinese banks. In perhaps the most explicit challenge to U.S. economic leadership yet, China’s “One Belt, One Road” initiative aims to establish China’s economic footprint as far north as Scandinavia, as far west as Spain, and all the way down to Eastern Africa, a space including roughly 65 percent of the world’s population and a third of the world’s GDP.

The Myth of Multipolarity

But while emerging powers can challenge American hegemony on a regional, and even continental scale, to assess world power on a purely regional basis would ignore the globalist reality of the 21st century. After all, regional powers like India and China would never be able to grow so rapidly without excessive demand from well-established powers in Western Europe and North America. In an interview with the HPR, Tad Oelstrom, the former director of the National Security Program at the Harvard Kennedy School of Government*, explained: “this world is no longer one that we can put in an envelope someplace and say, ‘this is the piece we worry about, and the rest of it [is] inconsequential.’”

From a global perspective of power distributions, America remains perched safely upon its pedestal as the world’s premier economic and military power. Although the emergence of regional powers prevents the United States from throwing its weight around as it did in decades past, the United States remains the bedrock for global commerce. It accounts for nearly 25 percent of the world’s GDP, and two of its closest economic partners, Japan and the European Union, account for an additional 28 percent. Of the next nine strongest economies in terms of GDP, the United States ranks among the top four export recipients for each. While economic powers like India and China continue to rise, maintaining a healthy U.S. economy remains crucial for their growth.

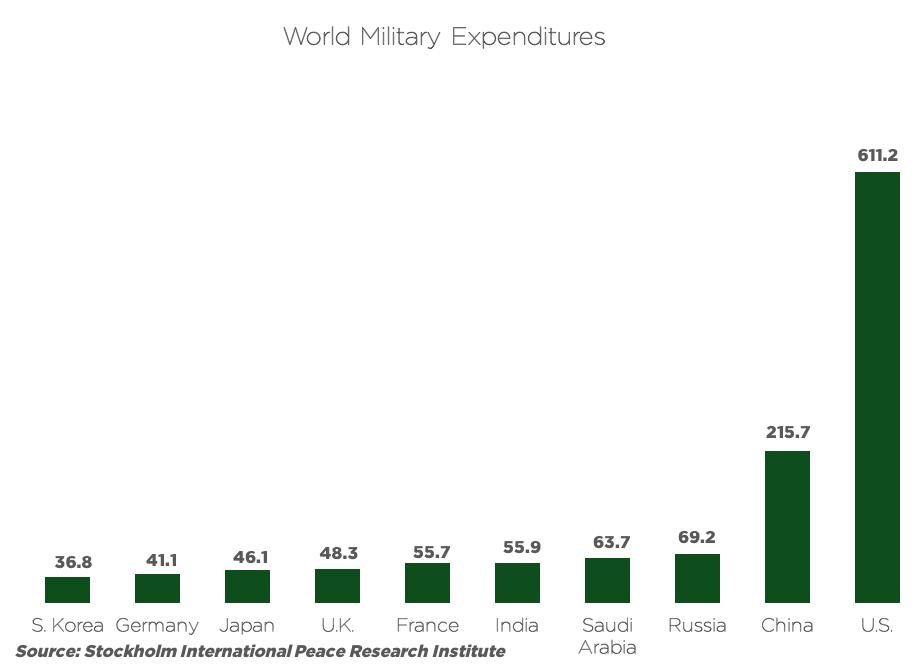

In terms of military expenditures, the United States spends nearly $20 billion more than the world’s next eight highest spenders combined. Of the next nine highest spenders, six are close allies of the United States.

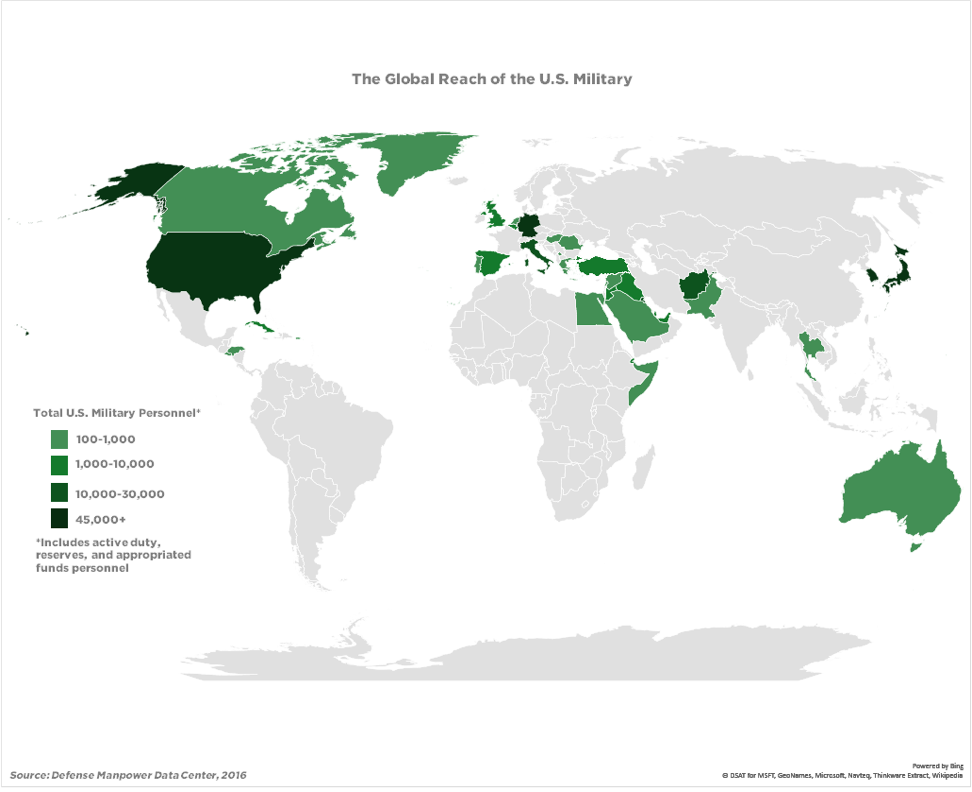

But what distinguishes the United States from the next highest spenders is its ability to project force around the globe. Through its vast naval superiority and international network of military installations, the United States projects its power to secure what Oelstrom called “global commons.” Ranging from the high seas to the open sky, these commons serve as avenues through which nearly all goods transfer between states and non-states. By securing these commons, states allow for the safe passage of shipping and travel throughout the world.

America’s navy remains its most versatile tool of force projection, and consequently, what distinguishes it most from the other world superpowers. While China and Russia claim impressive land capabilities, the fact remains that 90 percent of the world’s goods travel by water. No matter how many regional powers continue to challenge U.S. hegemony in different corners of the globe, none can match the global reach of the U.S. Navy.

The gap between America’s navy and the rest of the world’s is exemplified best by its marquee vessel—the aircraft carrier. The United States leads the world with 19 aircraft carriers in its arsenal. France comes in second with only four. Russia and China own a combined three, each with a tonnage of roughly 43,000, compared to America’s newest carrier, the USS Gerald R. Ford, which boasts a displacement of 100,000 tons. American carriers also account for roughly 70 percent of the combined tonnage of the world’s aircraft carriers.

Combine its numerous carriers with its extensive forward operating base network, and the U.S. military can threaten rapid land, air, and sea deployments anywhere on the globe. The United States maintains roughly 800 military bases in 70 countries abroad, and stations more than 275,000 overseas personnel in more than 160 countries. Meanwhile, China claims only one foreign military base in Djibouti, and Russia touts only nine, all concentrated in Eastern Europe and the Middle East. Until another country gains this ability to project power anywhere on the globe, America will continue to lead the way in securing the global commons, and thus the international flow of goods.

Theorists favoring multipolarity correctly identify the diminished ability of the United States to impose its will upon other countries. But the United States remains the only nation capable of securing the peaceful globalist structure of trade and commerce so many developed and developing countries rely on. Therefore, the ambitions of rising powers are checked by the disincentive of destabilizing U.S. power.

For example, the solidified role of the U.S. dollar as a centerpiece to the international economy was recently described in a piece by Kimberly Amadeo in The Balance: “the United States is the world’s best customer … the very countries that could cause a dollar collapse are those who need Americans to keep buying their products.” In his article titled “The Age of Nonpolarity,” Foreign Affairs scholar Richard Haas wrote: “many of the other major powers are dependent on the international system for their economic welfare and political stability. They do not, accordingly, want to disrupt an order that serves their national interests.”

The Rise of Non-State Actors

Consequently, most scholars don’t fear a dangerous collapse of American power in the foreseeable future. Instead, what alarms most analysts is the instability originating from the one global commons the United States remains unable to dominate—the internet. By freely diffusing information to many non-state actors, the internet has granted them significant influence on the world stage. These actors, though bound by their lack of conventional warfare capabilities, can leverage their significant clout in the digital realm to go toe-to-toe with even the world’s superpowers. Add these non-state powers to an already shifting world stage, and friction appears inevitable.

Nowhere has this potentially dangerous diffusion become more apparent than in the cyber successes of terrorist groups like ISIS and Al-Qaeda. While the United States has decimated each group’s conventional military capabilities, terrorists continue to wage successful worldwide recruiting efforts through the internet. One expert on terrorism told Harvard Distinguished Service Professor Joseph Nye that the most effective place for recruiting terrorists is “neither Pakistan nor Yemen nor Afghanistan …but in a solitary experience of a virtual community: the ummah on the Web.”

The diffusion of information catalyzed by the internet has empowered more than just terrorists. Non-state ‘hacktivist’ groups like WikiLeaks, along with state-sponsored cyber groups like the Russian “Fancy Bear,” have wielded significant political sway in Europe and the United States. Global corporations like Amazon, media outlets like BBC, and even social media sites like Facebook have also gained significant international influence due to the internet.

However, assertions that a world with non-state actors will be “difficult and dangerous,” as Haas wrote, confuse friction for conflict. While the many state and non-state actors often have opposing interests, most of these actors, with the exception of increasingly-weakened terrorist groups, have an interest in maintaining the stability of the current world order.

The withdrawal of Google’s Chinese search service in 2010 demonstrates both the modern power of non-state actors and their desire to maintain the current order of global power. As Nye noted, Google “inflicted a noticeable cost upon Chinese power” when it announced its decision to withdraw its search engine in China. Though China offered a significant market for Google, Chinese security attacks on Gmail threatened to compromise the brand’s invaluable security reputation, forcing the company to cease its search service there. According to Nye, “Google needed to preserve the soft power of its reputation for supporting freedom of expression to recruit and nurture creative personnel, and the security reputation of its Gmail brand.”

The tension between Google and China even rose to the interstate level. Before Google announced its withdrawal, Nye observes, it informed the Obama White House, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton incorporated the news into “a speech on internet freedom,” aimed at China.

Despite the ensuing political name-calling between the United States and China, the general outcome for each player was positive. As Nye notes, while China reasserted its authority on internet access, the United States further solidified its stance on internet freedom, and Google reaffirmed its security promises to its customers. Despite their disagreements, each actor reserved any outright hostility because each understood that future economic opportunity rests on a stable relationship between all three.

Like Google, nearly all of the non-state players who have emerged as a result of the internet’s diffusion of information have an incentive to maintain the global political stability that preserves it. Alibaba CEO Jack Ma said at a July event in Detroit, “If you missed the chance to sell to the USA, you missed your chance to grow. If you’re missing the chance to sell into China, you’re missing the future.” For their companies to compete on a global stage, countries must maintain their access to both well-established markets like the United States and rising economies like China and India. That means maintaining the U.S.-led institutions that secure this access.

Trump’s reluctance to support international institutions like NATO, along with declarations of China’s push for “Everything Under the Heavens” have led many to pronounce the United States’ demise as top dog on the world stage. An article from Valdaiclub.com even reads: “November 8, 2016: The Day American Hegemony Died.” But the reality is captured by the title of a Wall Street Journal op-ed written by Trump’s national security advisor H.R. McMaster and chief economic advisor Gary Cohn: “America First Doesn’t Mean America Alone.” What multipolar theorists and even Trump himself can’t deny is that the United States benefits from its role as a uniquely powerful, global leader.

Although the rise of regional powers and of non-state actors has diminished U.S. capacity to project power abroad, the system of global governance it has maintained since World War II is simply too beneficial for any rising actor to seriously consider challenging it. Until that system ceases to benefit the United States, or even less likely, another country emerges as a potential substitute to American leadership on a global scale, the U.S. will continue to lead the world. For now, the power rests in America’s hands.

Image source: Wikimedia/U.S. Pacific Fleet

*Correction, October 10: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated Tad Oelstrom’s affiliation with the Harvard Kennedy School. Mr. Oelstrom has retired from his position as the director of the HKS’s national security program.