Recent shifts in the upper echelons of Chinese leadership have attracted international attention. Chinese President Xi Jinping became the first leader since Chairman Mao Zedong to be addressed with the honorary “lingxiu,” or revered leader. He was also named “the core” of the Chinese Communist Party and his political philosophy was entered into the Chinese Constitution–just like Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. The media response has been less than favorable, with alarm bells ringing over concerns of figurehead idolatry and goals of political censure.

However, it is important to draw a line between the individual intentions of the President, his rhetorical power, and the impact of his political outlook. His consolidation of power is mediated by broader historical and political factors, and his rhetoric stands to combat Chinese vulnerabilities on a cultural, economic, and political level, bolstering China’s national identity and global position. Nevertheless, it is fundamentally uncertain whether these ideas of national advancement will functionally come to fruition in the near future.

The Not Unprecedented Title

Xi Jinping’s assumption of the “core” and “lingxiu” titles has inspired its fair share of concern, but is ultimately not a significant deviation from the established progression of governmental rule in China.

On the one hand, according to the “core” title, Xi Jinping is now able to override other members of the Politburo Standing Committee and is the ultimate authority in the Chinese Communist Party. This is a step back from “collective authority” shared under the previous dispersion of authority under the Standing Committee, and has been interpreted as an overreach of power. Nevertheless, the “core” title has been shared by multiple Chinese leaders. Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping, and Jiang Zemin all received the title of “core,” and Hu Jintao was reportedly offered the title, but declined.

Additionally, although Xi Jinping is undoubtedly still the first to be called “lingxiu” since Mao Zedong, experts argue that this term no longer carries the same force as it did in the Mao Era. Chris Buckley of the New York Times and Fraser University’s Jeremy Brown assert that a Xi Jinping cult will neither elevate the President to a godlike status nor mirror the intrusiveness of Mao’s policy, given increased Chinese participation in international institutions, the growth of the internet, and societal opening. At best, it will only bolster Xi and the Party’s image.

Additionally, Xi’s thoughts themselves are not a distinct jump from past precedents, prioritizing Chinese prosperity and the role of the Party. Harvard T.M. Chang Professor for China Studies, William Kirby, posits in an interview with the HPR, “Xi Jinping Thought looks to be a culmination of different agendas, and the dream of a strong China has been a dream of Chinese leaders from the Empress Dowager to the present. The central political message that Xi conveys is that in all areas, the leadership of the Party is paramount.”

The Chinese Communist Party remains crucial, and the ideology of progress is core. If not a significant expansion of power or radically different from past foundations, what difference does Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power stand to make?

Reviving China’s Identity

Although not a significant deviation from the past, Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power responds to cultural vulnerabilities, and his rhetoric adds focus to the cultivation of China’s future identity. Xi’s political reaffirmations come in step with the erosion of a longstanding way of life and the recent rise of consumerism on the mainland. Notably, consumerism has dealt a significant blow to the preservation of the broader societal landscape, manifesting in the large scale decimation of traditional architecture and dismissal of Confucian values of modesty and moderation under commercial holidays like “Single’s Day.”

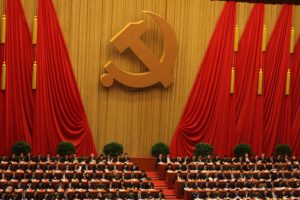

18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, 2012.

Despite its clear political role in strengthening the Communist Party, Xi’s “ascendancy” stands to enable a revitalized push for that which is distinctly Chinese, particularly in the Chinese application of socialism and an emphasis on long held values. According to Michael Peters in the Educating Philosophy and Theory Journal, Xi Jinping’s “thoughts” add impetus to the Chinese dream of sustainable prosperity and a strong national identity, broadcasting a historically relevant but modern socialist narrative through nationwide initiatives.

Furthermore, by utilizing the “lingxiu” title and drawing a parallel between himself and Mao, Xi emphasizes values, evoking the resourcefulness, drive, and humility associated with his own personal climb through the Party. This does serve a purpose of propaganda for both Xi and the Party, but it also leaves Xi’s image as a potential stepping stone for balancing Chinese ideals of morality and perseverance with a more open economic agenda. In this way, Xi’s outlook stands to promote Chinese ideological and cohesion and push the country forward.

Testing Waters

Politically, Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power correlates with the international image China hopes to project in the face of new political vulnerabilities. With intensified Sino-Japanese tensions in the East China Sea, a stalemate in the South China Sea, and new military developments in South Korea, China is testing the waters in East Asia. This, coupled with a relative American withdrawal from the region, has pushed China to define its global role for the coming years.

Xi Jinping’s consolidation of power gives increased voice to this foreign policy vision. In fact, Xi is at the center of China’s international dynamic, and China’s future direction depends largely on his leadership. Zhang Baohui, Professor of Political Science at Lingnan University in Hong Kong posits in an interview with the HPR, “Chinese foreign policy is increasingly becoming concentrated in the hands of one person, and that is Xi. He will be the most important factor in shaping China’s future impact, either in a positive or negative direction.”

Rhetorically at least, Xi’s vision looks to benefit China. During the 19th Party Congress, Xi emphasized national rejuvenation, using the phrase a total of 27 times, focusing on China’s rising position in relation to the West. His rhetoric is geared at generating greater political influence for China on a broader level, while simultaneously reaffirming the strength and necessity of international institutions. This is a step forward from past inward-focused policy, and promises to push China forward in the global arena.

Xi has also pushed forward the One Belt One Road initiative, an infrastructure project that retraces the past connections of the Silk Road. Spanning 68 countries and over 150 billion dollars of annual Chinese investment, the initiative is a clear example of China attempting to take an influential global lead. In this way, Xi’s centralization of power mirrors China’s efforts to broaden its influence, and it is this image of strength and direction that is poised to assuage concerns about China’s international significance and advance the country as a whole.

A New Economic Opening

The Chinese economy is facing a variety of challenges. Kirby sheds light on potential obstacles, “One of the major issues is the question of whether or not state owned enterprises will be reformed. Meanwhile in the private sector, large and medium business have been forced to open Party cells and this will likely have some effects on investment decisions and strategic directions.” Politicization and state ownership are not the only issues on China’s mind; environmental problems drain 3.5% of the annual GDP and the last few decades have left behind striking economic inequality.

Skyline of Shanghai, China.

Xi Jinping’s rhetoric attempts to provide an answer to some of these obstacles. The elevated recognition of his leadership is anticipated to make it easier to push forward a plan of ecological protection and to bridge societal gaps generated by the last decades of economic growth. Open development, increased quality of life, and and a general clean up of Chinese industry form the core of his outlook, providing a response to environmental and social challenges. On this end, he has delivered in the past. Zhang indicates, “Xi Jinping was very popular in his early years because he allowed the Chinese people to be felt. He cracked down on corruption, and implemented many new social policies that increased income.”

Furthermore, through the inclusion of his thoughts into the Constitution, Xi Jinping pledged a commitment to balanced and sustainable economic growth, with an emphasis on competitive globalization and greater market access with protection of foreign investors’ interests and rights. According to analysts, Xi’s agenda will likely result in lowering the economic growth target to a stable 6-6.5% in the coming years and stands to generate more opportunities for foreign companies. However, despite the rhetorical positives, the integration of Party cells has become a deterrent to some businesses and the state has sought to expand its regulatory influence, not curtail it.

A Practical Impact?

Rhetoric aside, the historical record of effectively applying broader ideological policy in China has not always been successful. As Kirby points out, “In Xi Jinping’s first year in office, there was significant rhetoric about major economic reform with the market taking the lead, and so far little of that has happened. State enterprises have become stronger and not weaker.” Despite governmental affirmations, China has still not reached the level of openness of a conventional market economy, and implements policy that clashes with its ideological aims, with increased government and party involvement in the economy.

Similar reservations apply to Chinese political consolidation. On an international front, China’s initiatives, like One Belt One Road, are often viewed as impractical expansionism and difficult-to-realize idealism. Zhang indicates, “China is on a quest for influence, but it may have prematurely committed itself to a global posture of preeminence that will ultimately exhaust China’s domestic resources.” Despite the potential gain it can bring China, Xi Jinping’s push for progress does not alleviate domestic difficulties, and comes against a background of uncertainty.

Nor is Xi Jinping the sole contributor in advancing national ideals. Professor Kirby indicates, “President Xi has talked about his admiration for cultural continuity and the study of classics, but the study of the classics is getting stronger less because of government initiative than because of popular interest.” A greater emphasis on Chinese values and ideals is a holistic societal effort, and Xi’s particular emphasis on the Chinese application of socialism and cultural uniqueness may not necessarily be compatible with international dynamics, as Zhang notes, “Xi emphasises China’s uniqueness, that the Chinese way is the right way and the better way. This is an ideological model that may generate friction with the West.”

While Xi’s current direction complements the national goals of bolstering the national economy, strengthening China’s geopolitical position and creating a platform for expressing China’s needs on a global stage, it is unclear whether Xi will effectively translate his rhetoric to practical consequences, particularly when it comes to balancing the Party’s internal interests and broader ideological aims. Xi has posited a framework that stands to assuage Chinese vulnerabilities, but it remains to be seen whether his stance will cause impactful change, or merely function as a new set of assuring platitudes. As Zhang says, “Xi definitely has the power to implement his policy, but whether he will use this historical opportunity to transform China, that is an open question.”

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Kremlin.ru // Wikimedia Commons/voachinese.com // Flickr/Riku Lu