Ten years ago, the nation’s future fiscal health seemed assured: an economic boom and the lack of significant external threats created budget surpluses. In 2001 the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) even projected that over the next decade the nation would enjoy a $5.6 trillion surplus. Politicians gleefully debated how to best utilize the windfall, ultimately spending the expected surplus on the Bush tax cuts, combat missions abroad, and programs like prescription drug coverage for the elderly.

But economists are not soothsayers, and the CBO now projects that debt will equal 185 percent of GDP by 2035 unless momentous policy changes are enacted. Like a company that finds itself mired in the red, the nation is reviewing its revenue sources and expenditures. Last year, President Obama appointed a bipartisan commission—called the Bowles-Simpson commission for its co-chairs—to perform precisely that analysis. Though its proposals never received official consideration by legislators, economists believe the thorough redesign of the tax system recommended by the commission is necessary. Policy makers must consider three core factors: simplicity to taxpayers, equity, and promotion of economic efficiency. Yet oddly enough, of all places debt-plagued Europe may provide an additional revenue mechanism for combating the American debt crisis.

Income Tax: Simplification for Taxpayers

When President Bush’s signature tax cut legislation became law, legislators and administration officials alike envisioned that tax receipts from the nation’s increased output would counter any reduced revenues in the form of tax cuts. What happened then? Congressional Democrats and the administration are eyeing eliminating these tax cuts for the wealthiest Americans to close an ever-widening budget deficit. President Obama has proposed ending them for individuals making more than $200,000 and couples making more than $250,000 annually. The liberal Center for American Progress has estimated that keeping the tax cuts for the wealthiest two percent would directly increase the debt by $690 billion over the next decade, with an additional debt service cost of $140 billion. The Progressive Caucus in the House went even further, proposing ending all Bush tax cuts and increasing taxes on the wealthiest Americans to raise $3.9 trillion over the next decade.

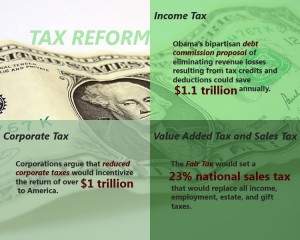

But Obama’s bipartisan debt commission proposed a markedly different strategy, calling for the elimination of all tax expenditures, which are revenue losses resulting from tax credits and deductions. The commission estimates that approximately $1.1 trillion is lost annually through these measures, and the loopholes merely add to the increasingly byzantine tax code. These deductions led the Tax Policy Center, operated by the Urban Institute and Brookings Institution, to estimate that 48.5% of households paid zero income taxes in 2008.

The commission’s proposal has received bipartisan support as a revenue-neutral reform of the tax system. Senior tax policy analyst for the conservative Heritage Foundation, Curtis Dubay, agrees that we must “reduce economically unjustified deductions and credits that litter the code.” Notably, the commission recommends that only $80 billion be reserved for reducing the deficit, while the rest would be utilized for lowering tax rates across the board. The debt commission recommends simplifying the tax code further, decreasing the number of income brackets from six to three, and decreasing the highest marginal tax rate from 35 to 24 percent.

Not only would this greatly simplify the tax code, but it would also mitigate the reduced savings that income taxes naturally cause. “Increasing marginal tax rates is a bad idea, since this would affect incentives to work and save adversely,” says Harvard economics Professor Dale Jorgenson. “A much more promising approach is to reduce average tax rates by eliminating tax credits and deductions.”

Strengthening Jorgenson’s call for simplicity, the Tax Policy Institute notes that tax expenditures “are most valuable for high-income households,” and House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan (R-WI) stated that eliminating tax expenditures, “would stop diverting economic resources to less productive uses, while making possible the lower tax rates that provide greater incentives for economic growth.”

Another weakness of the current tax system is the alternative minimum tax (AMT), which was initially designed to ensure that the wealthy paid their fair share. After numerous calculations, taxpayers would be presented with both the standard and the alternate tax, and pay the higher of the two. For over four decades, the AMT operated parallel to the standard income tax system. Despite the AMT’s laudable goals of closing loopholes, an unintended consequence arose: because the AMT is not indexed to inflation, it has slammed an increasing number of middle class citizens whose salaries have largely kept pace with inflation. According to the CBO, the AMT has gone from affecting less than one percent of taxpayers before 2000 to affecting 16 percent of taxpayers in 2010. Both Bowles-Simpson and another bipartisan tax reform proposal from Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) and former Senator Judd Gregg (R-NH) propose eliminating the AMT.

There is general consensus from both parties that too many tax expenditures exist. But excessively partisan proposals from both ends have made little headway towards the lofty goals of increased economic productivity and deficit reduction. Some conservative Republicans have opposed closing expenditures, deeming that akin to raising taxes, while other progressive Democrats believe that increased taxation on the wealthy is an essential pillar to debt stabilization.

Corporate Tax: Making America Competitive Again

With significant obstacles to income tax reform, policy makers have turned towards another revenue source: American businesses. Every year, multinational corporations keep profits stored in overseas accounts to avoid paying relatively high marginal corporate tax rates. Any company with taxable income exceeding $18.3 million, which includes all major corporations, is subject to the 35 percent marginal tax rate, minus taxes already paid overseas. For example, if Google made $2 billion in profits in Ireland and then transferred those profits back to the United States, it would first pay 12.5% of that profit to Ireland, before paying 22.5% to the U.S. government. This makes repatriating profits an unattractive option, and leads companies to keep resources offshore.

According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, once Japan completes its planned reduction of the corporate tax rate, the U.S. would be left with the highest corporate rate among industrialized, democratic nations. The Win America campaign, a coalition of several dozen corporations, including Apple and Google, has proposed a temporary reprieve that would dramatically lower the corporate rate from 35 to 5.25 percent. These multinationals argue that this would incentivize the return of over $1 trillion, which companies would then utilize to invest and hire new employees.

A corporate tax reprieve has been tried before, but with questionable success. The 2004 Homeland Investment Act did not contribute to domestic economic growth, concluded economists Dhammika Dharmapala, C. Fritz Foley, and Kristin Forbes in a 2009 National Bureau of Economic Research paper. Their research shows that most of the repatriated money actually went towards paying dividends rather than reinvestment and hiring new employees. Opponents further argue that offering a windfall on repatriation would unfairly punish companies that did transfer money overseas back into the United States.

But, the Win America campaign raises a pertinent concern: the corporate rate is excessively high. Martin Feldstein, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisors for President Reagan, wrote in the Wall Street Journal on February 15, 2011, that “The high corporate tax rate causes a misuse of our capital stock. More specifically, the high rate drives capital within the U.S. economy away from the corporate sector and into housing and other uses that do not increase productivity or raise real wages.” High business taxes raise the cost of capital and encourage companies to invest abroad. The Bowles-Simpson commission proposes reducing the rate from 35% to 27% in conjunction with closing corporate tax loopholes, which would make American companies more competitive with foreign ones while being deficit neutral.

Progressives have been infuriated by stories of companies like General Electric, which actually claimed $3.2 billion in tax benefits even though it made $14.2 billion in profit in 2010. The outrage translated to demands for higher corporate tax rates. But reduced marginal tax rates and sharply limiting deductions would most greatly improve economic efficiency. Not only would companies greatly curtail time spent on bureaucratic paperwork dealing with taxes, but the provisions recommended would also incentivize corporations to return overseas profits for investments or dividend payments which could then be taxed. The current business tax structure must be overhauled to help American business compete in emerging markets abroad.

Value Added Tax (VAT) and Sales Taxes: Reducing Savings Distortion

Beyond the traditional income and corporate taxes, other economically developed nations have targeted consumption. The VAT, unlike income or payroll taxes, targets the American pastime of consumption and minimally impacts savings and investment, which economists believe Americans do too little of. President Obama was criticized last year for broaching the politically taboo subject of the VAT as an opportunity to raise additional revenue. Conservatives immediately countered by stating that the debt arose primarily because of spending, not revenue, and that Bowles-Simpson did not recommend the VAT.

But economists have been more receptive to the concept as part of an overall reformation of the tax system. European nations in particular rely heavily on the VAT, and the European Union requires its members to have a VAT of at least 15 percent.

The value added tax in theory collects the same amount of revenue as a sales tax, but instead levies the tax at various levels of production. Foreign governments have also imposed various credits to avoid double taxation. Consider the following example with a five percent VAT: a pencil maker purchasing $1000 in wood would pay $50 for his purchase. However, if the pencil maker had spent $400, with an additional $20 VAT, for machinery, then the final VAT paid by the pencil maker would be $30. Since corporations would merely collect the taxes for the government, and consumers would not file tax returns, this is an attractive alternative to the income tax. “As a form of fundamental tax reform a VAT is more viable,” says Dubay. “In theory it is a more economically efficient tax than our current system.”

Although a formal VAT proposal has not been floated, conservative legislators have proposed the Fair Tax, a 23 percent national sales tax that would replace all income, employment, estate, and gift taxes. The Fair Tax would offer an annual rebate for all taxpayers to mitigate the effect that the national sales tax would have on the poor. This falls more in line with Harvard public policy expert John Donahue, who argues, “a tax levied on consumption that spares the first chunk of household spending, falls lightly on consumption up to middle-class levels, and more heavily on luxury purchases and/or very high levels of aggregate household consumption seems like a great idea.”

Already, U.S. taxes on consumption average 4.7 percent of GDP, through state and local sales taxes that apply to particular commodities. The gasoline tax, currently 18.4 cents per gallon, accounted for 35.4 percent of all excise taxes in FY 2009 alone. Economists generally agree that taxes that counter negative externalities, like pollution, enhance overall economic welfare. To that end, Bowles-Simpson also proposed increasing the gasoline tax by 15 cents, raising the total federal tax to 33.4 cents per gallon. Currently, including both federal and state taxes, gasoline is taxed around 40 cents per gallon, much lower than the Eurozone, which taxes around $4 per gallon.

But, the gasoline consumption tax offers a glimpse into the potentially fatal flaw of a national VAT and sales tax: the poor and middle class spend a greater portion of their income on gasoline than the wealthy. The political will for imposing the VAT does not exist because consumption occupies a greater proportion of income for the poor than the rich. Without determining the various deductions necessary to reduce that inequity and simultaneously stopping special interests from carving out exemptions for certain products, taxing consumption on the national level is infeasible.

Political Machinations

Unfortunately, America’s fiscal health will remain in dire straits for the foreseeable future. But the recent budget negotiations over the debt ceiling entailed some core tenets of what economists have sought for years: the elimination of loopholes, reduction of across the board rates, and simplification of the tax code.

Once economic stabilization is achieved, policy makers should consider expanding the tax base via the VAT. With its inherent advantage of a potential $8.8 trillion tax base and minimal distortions of savings and investment, a VAT could be utilized to improve economic efficiency and reduce the income and corporate tax burden.

Design by Melissa Wong