Natoma Canfield is a 50-year-old cancer patient in Cleveland, Ohio. In 2009 she paid some $10,000 in deductibles after her insurance premiums increased 25 percent. Unable to sustain an additional 40 percent rate hike in 2010, she dropped her coverage, and has since been diagnosed with leukemia.

On his final health care push in Ohio, President Obama told the audience, “I’m here because of Natoma.” Ms. Canfield’s story is hardly unique: one study conducted by Harvard Medical School and Cambridge Health Alliance estimates that nearly 45,000 annual deaths are associated with a lack of health insurance. While the recent health care reform, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, will provide nearly universal coverage, its ability to put health care costs on a path to fiscal sustainability is less certain, dependent on congressional discipline and a hodge-podge of untested medical pilot programs.

Spiraling Spending

The United States spends significantly more on health care than any other industrialized country, yet covers a smaller proportion of its population. Rising costs are thanks in part to consumer demand over the past decades, which has fueled development of procedures. Treatment of chronic disease now consumes 75 percent of national health care costs as a result of our aging population, and administrative overhead accounts for 7 percent of expenditures.

Thanks to these and other factors, health care spending has grown from 7 percent of GDP in 1970 to more than 17 percent in 2009. Premiums have more than doubled since 1999, far outpacing worker earnings. As of 2007, some 15 percent of individuals were completely uninsured, and at least another 10 percent were underinsured, unable to fully pay their insurance deductibles and co-pays.

This is despite tremendous federal subsidies, a continuation of which would ultimately devour the federal budget. The Office of Management and Budget estimated that if current spending patterns continue, Medicare and Medicaid alone would cost 20 percent of GDP—the current level of all federal spending combined—by 2050.

Obama’s Reform

President Obama and the Democratic Congress sought to solve these problems with the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or PPACA, which the President signed on March 23, 2010. The complex law expands coverage with insurance market mandates: beginning in 2014, it bars insurance companies from denying coverage based on preexisting medical conditions and previous insurance claims. It also requires citizens to purchase federally approved insurance or pay a fine, with the goal of maintaining a financially sustainable risk pool for insurance firms.

PPACA increases affordability through $938 billion in subsidies over 10 years, much of which will fund state-level health insurance exchanges. By 2014, each state will have created an exchange in which families and employers can purchase private insurance plans that comply with federal guidelines. The federal government will provide refundable, means tested tax credits to families below 400 percent of the national poverty line. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that the exchanges will extend coverage to 24 million Americans.

The other avenue for affordability is the expansion of existing programs. By 2014, individuals not eligible for Medicare with incomes below 133 percent of the poverty level will be eligible for Medicaid, which will cover another 16 million citizens. The CBO estimates that the new exchanges and the Medicaid expansion will provide insurance to 94 percent of Americans and cost some $900 billion over 10 years.

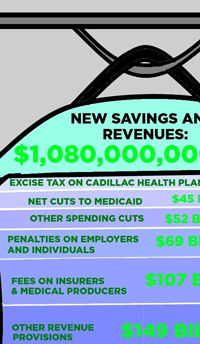

The law covers half of this cost with new taxes. It imposes an excise tax on high-cost “Cadillac” health plans, which begins in 2018 and raises a projected $32 billion through 2019. An annual fee on health care providers will raise $60 billion, and surcharges on individuals earning over $200,000 annually will raise $210 billion. These and other taxes will generate $410 billion through 2019.

The rest of the cost is covered by reductions in Medicare reimbursements to care providers, reducing spending by $491 billion through 2019. Perhaps most importantly, the law funds a series of pilot programs, like investments in medical information technology and penalties for hospitals with high readmissions, that test ways of slowing spending growth. The CBO expects the law to reduce the deficit by $143 billion in the next 10 years and by as much as $1.3 trillion over the following decade.

Bending the Curve?

While the law goes a long way toward universal coverage, there is continuing debate about its fiscal implications. Democrats have criticized the CBO for underestimating the bill’s savings provisions, while conservatives have criticized Democrats for attempting to game the CBO by phasing in reforms late in the 10-year estimate window to lower apparent costs. Even if the estimate is accurate, it only reflects the law exactly as written. If Congress lacks the political will to implement the new taxes and Medicare reductions come 2018, hundreds of billions of dollars in projected savings may never materialize.

And even if the law works exactly as written, it should be judged not only by whether it pays for itself in the short run, but also, as Professor Michael Chernew of Harvard Medical School explained to the HPR, by whether it puts us “on a path to fiscal sustainability.” Unless it bends the curve on medical expenditures, meaning it significantly slows growth, short-term deficit reduction will be futile. The law might improve affordability for individuals, but health care costs will consume ever-larger portions of national income, which must ultimately be financed through taxation.

The greatest hope for controlling long-run spending lies in the bill’s smaller subtitles, which offer uncertain but innovative pilots that could blossom into effective cost controls. The CBO is conservative in scoring these unpredictable policies: community wellness programs, comparative treatment effectiveness research, pay-for-performance systems, and other experimental initiatives are predicted to have zero savings.

Even those that register in the projections are minor. The new Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation, designed to explore new pay-for-quality systems, is slated to save some $4 billion through 2019. The biggest saver is a bonus created for hospitals with low readmissions, projected to save $14 billion.

Harvard economics professor David Cutler wrote in the Wall Street Journal that the law incorporates virtually every broad idea that has been offered for “bending the health-care cost curve.” Professor Katherine Baicker of the Harvard School of Public Health explained that although the pilots may be the key to fiscally transforming the health care system, they can only succeed if the workable ones are “implemented in full force.” Whether that happens is a question of politics.

PPACA has definite potential to rein in costs over the long term, but passing this one bill is not enough. Policymakers must recognize which parts of the bill are effective cost cutters, and Congress must have the political will to enact these provisions in full force while eliminating the unworkable ones.