The recent debt-ceiling crisis was more contentious than a Texas football game, as Democrats and Republicans rejected each others’ budget cut proposals. But this rivalry characterizes the current partisan political season. In April, the US prepared for a potential government shutdown while Democrats and Republicans struggled up until the last moment to agree on a budget for the upcoming fiscal year. And while the federal government narrowly avoided a shutdown, the Minnesota government shut down from July 1 to July 20 after a budget bill failed to pass.

For over a decade, we’ve avoided shutdown on the federal level, but the current partisan climate is reminiscent of the shutdowns of 1995 and 1996, where President Clinton and House Speaker Newt Gingrich battled over government spending. What would happen if the federal government did shut down? Let’s examine the circumstances in which the government would shut down. Which government agencies would take a hit, which would continue to function, and which would suffer collateral damage?

Why does the government shut down?

A federal government shutdown generally occurs when the legislature and president cannot pass a budget for the upcoming year. The legal basis for a government shutdown stems from the Antideficiency Act of 1870, which states, “[I]t shall not be lawful for any department of the government to expend in any one fiscal year any sum in excess of appropriations made by Congress for that fiscal year.”

In 1980, reinterpretation of the Antideficiency Act led to the modern conception of a government shutdown. Charles Tien, Department Chair of Political Science at Hunter College, explains to ARUSA, “In 1980, President Jimmy Carter’s administration, in reevaluating a law passed in 1870, decided that the Anti-deficiency Act ruled that agencies without appropriations had to close operations.” As a result, the government has shut down a total of 11 times since 1980, and ending each shutdown has required either a continuing resolution or a regular appropriations bill.

Who is furloughed?

According to the US Office of Personnel Management, a shutdown furlough is when an employee is placed in a “temporary nonduty, nonpay status because of lack of work or funds, or other nondisciplinary reasons.” It is estimated that a government shutdown would cause 800,000 employees to be furloughed. Moreover, compensation for furloughed workers in these agencies is not guaranteed. As Richard Keevey, faculty member at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton, notes, “It is questionable if people will be paid retroactively, even those still working. The government does not have to pay these workers.”

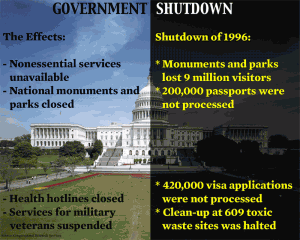

Several agencies deemed ”nonessential” would be closed either partially or completely in the event of a shutdown. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) would be closed, leaving hotlines unattended. The National Institute of Health (NIH) would delay new clinical trials. Normal passport services would cease, hindering travel plans. In the 1995-1996 shutdown, certain functions of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)—specifically the Superfund, which addresses hazardous waste sites—were suspended, leaving several hundred toxic waste dumps unattended. Other federal regulatory functions would also be suspended, including regular mine safety inspections, most functions of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission, and stockbroker inspections.

Additionally, the National Park Service would close. During the 1995-1996 shutdown, national parks and monuments lost 7 million visitors. Similarly, the Smithsonian estimated that hundreds of thousands would be turned away from museums and the National Zoo during a shutdown.

Who still comes to work?

Many government agencies and employees, however, would be less affected. Notably, members of Congress would continue receiving paychecks. While the Defense Department’s civilian employees would be furloughed, military personnel abroad would continue to work. Likewise, most Department of Homeland Security employees would continue to work, including airport security personnel, the US Coast Guard, and border patrol. The Postal Service would continue sending mail because customers already pay for services, and Social Security beneficiaries would continue receiving their checks. Other entitlement programs such as Medicare and Medicaid would also be unaffected.

Would we be prepared?

The White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) requires each government agency to have a contingency plan to ensure a systemic shutdown. Plans require the heads of agencies to “reallocate funds to avoid interruption of services for as long as possible.” In short, government agencies have emergency funds and pre-determined strategies to ensure that chaos does not ensue during a government shutdown.

Even though the government can avoid complete mayhem through successful planning of a government shutdown, it is, of course, a heavy burden on the hundreds of thousands of federal employees forced into unpaid “vacation” and the many Americans affected by a loss of service. Moreover, taxpayers could possibly be forced to pay hundreds of millions to cover shutdown costs for no benefit in services. According to the OMB, the 1995-1996 shutdowns cost approximately $1.25 billion. That’s a steep pricetag, particularly because the shutdown would ironically be caused by heated spending cut negotiations.

Design by Andrew Seo