Hidden beneath the public face of the government—the President, Congress, and the Courts—extends the vast iceberg of federal government. Regulatory agencies, bureaucracies and other organizations like the FBI provide millions of jobs and spend billions of dollars, impacting everything from agriculture to commerce to recreation.

Republican presidential candidate Michele Bachmann has described the current state of America as “overweening, huge, bureaucratic, large, big government.” Bachmann, affiliated with the Tea Party movement that swept much of the country, is not alone in her criticism. Joining the conservative push against “big government,” the Libertarian party, advocating governmental minimalism, has become the third largest political party in the United States.

That sentiment has caught on across the political scene. At this year’s State of the Union address, much of President Obama’s speech focused on the need to “merge, consolidate and reorganize the federal government.” While bureaucracy is necessary to implement and organize vital functions of government, policymakers—including the President—say that it can become excessively complex. One of the best-received moments of Obama’s speech cited a particularly convoluted aspect of the federal government:

“There are twelve different agencies that deal with exports. There are at least five different entities that deal with housing policy,” Obama explained. “Then there’s my favorite example: the Interior Department is in charge of salmon while they’re in fresh water, but the Commerce Department handles them when they’re in saltwater.”

While it is easy to mock such failures and make the DMV the punch line of your jokes, convoluted bureaucracy has become an inevitable reality in modern governance. Experts on both sides of the political spectrum say that there is no “right” amount of money that the government should be spending annually. Bureaucracy, despite inevitable flaws, is necessary and useful for a functioning country, although specifics of jurisdiction and funding can be subject to significant debate.

There is no one “federal bureaucracy,” says American University Professor Robert Durant. Instead, he says, it is better to think of the federal government as a combination of “‘holding companies’ comprised of a variety of agencies and programs, each with their own constellation of interests.” These agencies and programs include the largest and best-known agencies. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) are each further subdivided into semi-independent subgroups and programs (five divisions and 11 regional offices, and forty nine offices, divisions, and centers respectively). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), tasked with protecting the environment and human health, is a combination of over 14 different offices and 10 regional subdivisions.

“Public bureaucracies are not designed for efficiency,” Durant says. “They are designed through negotiations and compromise among competing interests to ensure that they will have power, access, and influence over later policy decisions made by agencies.” Durant says attempts to change the system from the top will be slow, since members of Congress are politically attached to the agencies that their respective committees oversee. “When you try to reorganize agencies, you have to simultaneously reorganize the congressional committee structures which oversee those agencies. And members of those committees are going to resist,” he says. Several commissions, for example, have now called for a single congressional committee to oversee the Department of Homeland Security, replacing over sixty separate committees that now oversee different departmental programs. Despite official reports touting the benefits of such a move, the President’s approval, and widespread public support, Congress has not approved the consolidation. The Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act of 2012, passed by the House on June 2, 2011, would delay funds for consolidation purposes for at least two years.

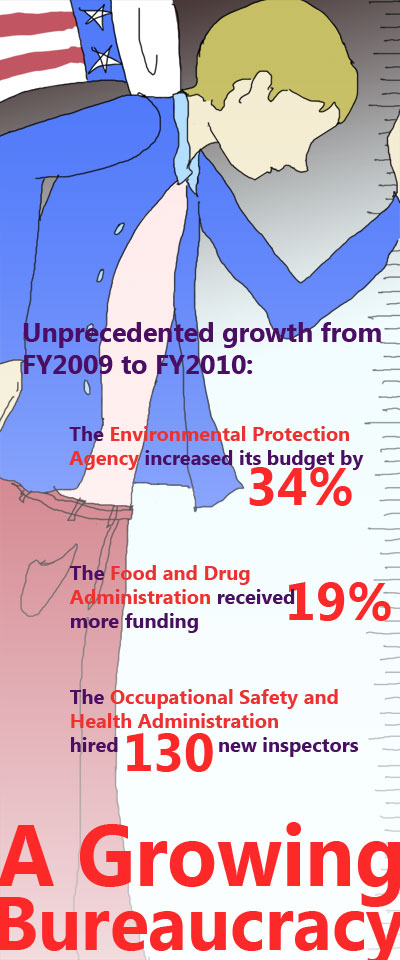

So what is President Obama’s record on bureaucracy? Funding for agencies increased over fiscal years 2009-2010, with predicted increases for 2011 as well. The Presidential Budget for the EPA requested increases of 34% in 2010 over 2009’s federal budget, the first time in eight years that the EPA has increased its funding. The FDA requested an unprecedented funding increase of 19%, the largest increase to date. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, charged with the enforcement of safety and health legislation, hired 130 new inspectors to ensure compliance with federal regulation with increased funding, $1095 million in 2010 compared to the previous year’s $906 million.

The Small Business Administration (SBA) released a study earlier this year estimating that regulation costs America $1.75 trillion. The paper, which adheres to an extremely loose interpretation of regulation, looks at all federal regulations, major and minor, including economic, environmental, tax compliance, occupational safety and health, and homeland security. Small-government conservatives point to studies like this to argue that reducing bureaucratic regulation would save the American government billions of dollars.

But the SBA study also begins its evaluation with the recognition that “regulations are needed to provide the rules and structure for societies to properly function.” Durant explains that regulations provide independent evaluation and insurance that markets are operating fairly, a process that is necessary for the economic confidence that is crucial to the American economy.

The debate between free market solutions and government bureaucracy is thus misplaced, Durant says. “The fundamental problem facing the U.S. is how best to harness for public purposes—and I stress public purposes—the dynamism and creativity of markets, the passion and commitment of nonprofit organizations and volunteers, and a public interest-oriented career civil service in public agencies,” he says.

Design by Melissa Wong