The Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA) is perhaps the defining bipartisan moment of the Clinton Administration. President Clinton promised it would “end welfare as we know it,” and he touted its success ten years later, declaring that it created “a new beginning for millions of Americans.” Not since FDR’s New Deal or Johnson’s Great Society has the federal government so fundamentally changed the way it administers welfare.

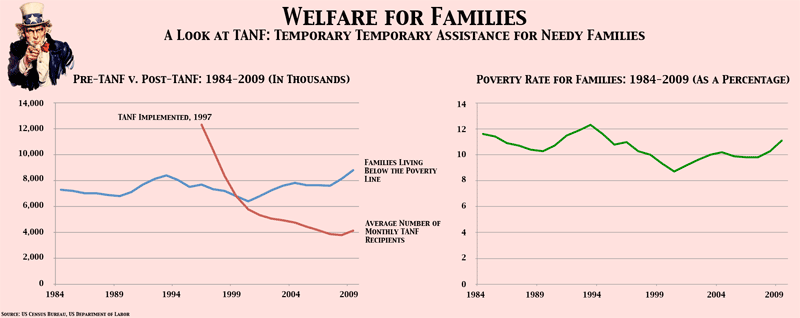

Welfare reform’s many programs, most notably Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF), operated under the framework of “work for welfare,” or “workfare.” Deemed a success due to declining poverty rates in the late 1990s, its effectiveness during the recession is now being called into question as states face tightening budgets and the federal government works to reduce long-term deficits. Discretionary spending like TANF is often the first area on the chopping block. But this threat occurs just as impoverished Americans are experiencing difficulty finding employment, a prerequisite for receiving assistance. Declining TANF caseloads coupled with increased poverty rates may be an indication that America needs a new paradigm in delivering welfare assistance.

An Illusory Success?

In a 2006 research paper, the Heritage Foundation’s Robert Rector, one of the primary architects of welfare reform, found that the reform helped decrease poverty rates. Citing a three percent decrease in the child poverty rate from 1995 to 2004, Rector discovered that “the declines in poverty among black children and children from single-mother families were unprecedented. Neither poverty level had changed much between 1971 and 1995.” Supporters of welfare reform also cite declining single mother childbirth rates and unemployment rates as further evidence of its effectiveness; according to Clinton, “sixty percent of mothers who left welfare found work.”

PRWORA critics point to the booming economy as a prime reason for the program’s success; employment was an easier requirement to fulfill in the late 1990s than after the recessions of 2001 and 2008. Indeed, while the average number of monthly TANF recipients declined from 12 million in 1996 to just over 4 million in 2010—a statistic often used to demonstrate PRWORA’s effectiveness—14.3 percent of Americans now live below the poverty line compared to the 15 percent before welfare reform.

A Center on Budget and Policy Priorities report reveals that “in 2005, state TANF programs provided cash assistance to just 40 percent of families who are poor enough to qualify for TANF cash assistance and who meet the other eligibility requirements for these programs,” in comparison to 80 percent under the previous program. LaDonna Pavetti, Family Income Support Policy expert at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, explained to ARUSA that “the rhetoric that still touts welfare reform as a success is based on what happened in the early years. If you look at the last fifteen years rather than just the early years, you get a different story…the share of poor families being served by TANF is extremely low in comparison to what it was at the beginning.”

The Emergency and Contingency Funds

Aware that states would face a heavier welfare load during the recession, the federal government established a $5 billion Emergency Fund as part of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. States could use the money in one of three ways: provide families with a monthly welfare check, make one-time payments to keep families off welfare, or subsidize private-sector jobs. To the surprise of many, including Brookings Institution expert Ron Haskins, states ended up creating over 250,000 jobs using the third option. In Haskins’ opinion, this option embodied the best of both worlds: “It addresses the problem of getting money to people when they can’t get a regular job, and secondly, it also does it in a way that is completely consistent with the welfare reform bill.”

The Emergency Fund was not extended in 2010, but with a pricetag of $5 billion, some believe the reason was more philosophic than economic. Pavetti believes that “Money wasn’t the main issue. That was very much a political issue…It was part of the stimulus and there was no willingness on the part of Republicans to extend anything that was a part of the stimulus.”

Because states must balance their budgets, unlike the federal government, the exhaustion of the Emergency and Contingency Funds constituted significant losses for welfare programs. Around thirty states saw an increase in welfare caseloads between 10 and 30 percent in 2010, but with no pool of extra funding from which to draw, states coped by cutting benefits, shortening time limits, and cutting external benefits like childcare. Haskins views this latter cut as particularly problematic, as childcare is vital for any welfare parent searching for a job, a prerequisite for receiving welfare benefits.

Time for a New Beginning?

Tougher economic times call for a new paradigm, and the rules developed in 1996 now appear to be falling short, especially after undergoing several amendments in the past decade that weakened the original law. Every state except Wyoming will receive less TANF funding in FY 2011 than in 2010, with a handful of states losing 20% or more of their block grant amount. But employment rates among impoverished families continue to fall. When asked by ARUSA, Pavetti explained that “lots of people said we won’t know if welfare reform is a success until we’ve gone through a recession, and now that we’ve been through a recession we can see TANF’s flaws better than we could have before.”

By all accounts, PRWORA was a historically bipartisan piece of legislation highly effective during a boom economy. But Washington must decide how best to balance work requirements with coverage, while adapting the rules developed 15 years ago to today’s economic realities. While Congress cut the Emergency Fund with debt reduction in mind, these discretionary programs are a drop in the bucket compared to Medicare and defense spending in their contribution to long-term deficits. Congress should set aside its political differences to pass reform legislation and spending cuts tailored to the current recession.

Design by Andrew Seo