Alex Burns is a senior political reporter for Politico. He published this article about changes to the leadership of U.S. intelligence agencies after 9/11 in the Fall 2004 issue of the Harvard Political Review, when he was a contributing writer. Burns graduated from Harvard in 2008.

On July 22, the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States released the final report on its investigations, to almost instant acclaim. In the New York Times, columnist David Brooks compared the commission’s report to George Kennan’s famous “Long Telegram,” an “all-encompassing epoch defining essay.” Detailing the precise ways in which the U.S. government failed to prevent the terrorist attacks, this report proposes a complete restructuring of the U.S. intelligence agencies so as to increase efficiency and decrease the risk of another terrorist attack.

Though some have objected to these changes, many familiar with the intelligence community believe that restructuring the top of the American intelligence apparatus is an important move towards meaningful and long-lasting intelligence reform. One major component of the suggested restructuring is the creation of a national intelligence director, who would replace the current director of central intelligence as the head of the American intelligence community. The NID would not necessarily have direct budgetary power over all intelligence agencies, but could still be granted hiring and firing power at the top levels of intelligence management, a power the current DCI lacks.

Parsing the Report

Former Nebraska Democratic Sen. Bob Kerrey, a member of the 9/11 Commission, told the HPR in a recent interview that the commission’s recommendations are “modifications of a recommendation that have been made in the past. There are about 15 agencies in the U.S. intelligence community, and the current DCI has control only over the CIA. We want to create a new position above the CIA and other agencies that will have the authority to direct the people in those agencies.” With greater oversight power than the current DCI, the NID would be able to much more effectively control the agencies he supervises.

As described in the 9/11 commission report, the National Intelligence Director would be a cabinet-level position that directly manages the budget and personnel of the US intelligence community. The NID would report to the president and would be assisted by several deputy national intelligence directors, each of whom would manage a specific kind of national intelligence: foreign, defense, or homeland. Kerrey is optimistic that with such restructuring “you’re going to get significantly improved reporting and use of available intelligence.”

The Pentagon Responds

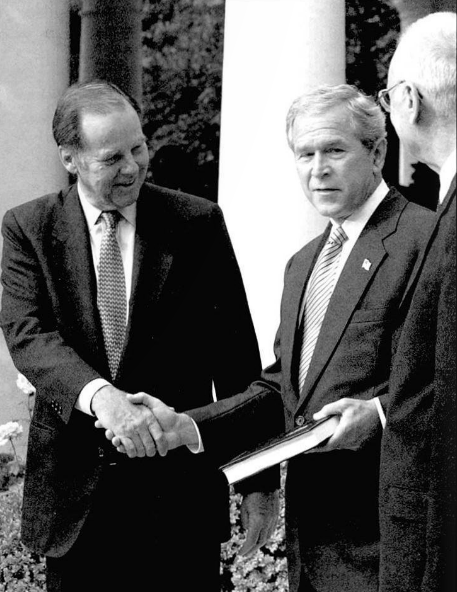

However, the process of creating such a position and effecting massive restructuring is not merely as easy as simply devising a plan. Indeed, the responses from the Defense Department to the 9/11 Commission’s suggestions were lukewarm, at best. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld told the Senate Armed Services Committee that enacting the proposed reforms could at best bring about only “some modest but indefinable improvement.”

Rumsfeld also voiced concern about how the proposed reforms would affect combat operations. “We would not want to place new barriers or filters between military combatant commanders and [the Pentagon’s intelligence] agencies when they perform as combat support agencies,” he said. In his view, a new intelligence director would effectively place obstacles in the way of efficient force protection, with consequences, especially in battle that could be grave.

Secretary Rumsfeld’s unease is legitimate, but could be easily remedied, according to Vicki Divoll, former assistant general counsel for the CIA and general counsel to the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, in an interview with the HPR. According to Divoll, the Defense Department is “legitimately concerned on an operational level… that if they are unable to collect intelligence to protect their troops in the field, that could be very dangerous. Most people agree, though, that the Department of Defense should retain power over force protection intelligence.”

Kerrey confirmed this opinion. “National intelligence is different from military intelligence,” he said. “In some cases, the Defense Department has said, ‘We’re going to have to give up control over military intelligence.’ This simply isn’t true.”

Managing the Managers

The Pentagon’s concerns, however, are not the only worries that have emerged about appointing an NID. Divoll cited former Director of Central Intelligence George Tenent’s concerns that an NID would essentially only manage other managers, and would constantly be concerned about having too little political support. As Divoll put it, “the only drawback I have ever heard articulated is, if you do not have your own constituency, then you don’t have the power. The National Intelligence Director is going to have to show up at the White House, if he’s invited, with no base of his own.” The potential isolation of such a position could pose significant operational challenges and limitations.

Still, despite this apprehension, Divoll endorses the restructuring described in the commission’s report. “It’s a good idea,” she said, explaining that the appointment of an NID would result in other meaningful reforms. “You make these changes in the hope that the first NID comes in with the will, the power, and the money to do top-to-bottom reform.” In other words, one of the NID’s most important functions would be to set the intelligence community on a course of even greater change.

Moving forward

At first, it appeared that many members of Congress, both Democrats and Republicans, agreed with Divoll’s positive assessment of the 9/11 Commission’s recommendations. Maine Republican Sen. Susan Collins and Connecticut Democratic Sen. Joseph Lieberman sponsored and helped secure passage of the bipartisan National Intelligence Reform Act of 2004, which called for the creation of a powerful NID. “The Collins-Lieberman bill is excellent,” Kerrey said, nothing that “it not only incorporates most of what the 9/11 Commission recommended, but improves upon it.”

However, Republicans in the House passed a restructuring bill that accedes to many Pentagon complaints and would make the NID much less powerful. Indeed, Kerrey’s evaluation of the House bill was much less positive, and as of this writing, the House-Senate conference committee had been unable to work out a compromise on the bill, which threatens to derail timely creation of an NID.

According to Kerrey, the House bill is “unacceptable.” As it was drafted “with no Democratic involvement and practically no attention to the Commission’s recommendations.” Though many members of Congress support the commission’s recommendations at least in the abstract, there are clearly significant differences of opinion with respect to how and even if they should be carried out.

With the continued threat of terrorism and the emphasis on homeland security in the presidential campaign, it is possible the American public will not tolerate such a congressional stalemate. Demand for intelligence reform is real, not just in Congress, and speedy establishment of a true director of intelligence, whatever the position ends up looking like, will surely remain a top priority.