Truth is, if you have read a Dan Brown novel, you have read them all. To a lot of readers, Dan Brown’s newest installment in the adventures of the fabled Harvard professor of symbology Robert Langdon will feel and read like a deja vu. The adventure, the mystery and the pretty girl is a formula that worked well for his past bestsellers, and that is what the reader can expect to find in Inferno as well. Though it did not have the same amount of decoding and deciphering that made The Da Vinci Code and Angels and Demons contemporary hits, its reliance on the fascinating symbology found in Dante’s The Divine Comedy and the lively descriptions of Florence made up for the ‘barely there’ mystery and decoding. On the overall, Inferno will pique most readers’ interest and can rightfully be dubbed a page-turner.

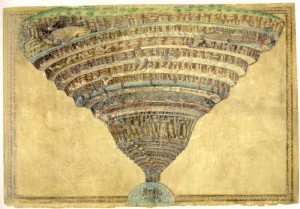

When it comes to plot, no one can accuse Dan Brown of not being innovative. The novel starts off with Robert Langdon waking up in a hospital chamber, suffering from amnesia and unable to recall the events of the past forty-eight hours of his life. There he meets the Sienna Brooks, a pretty young doctor who turns out to be a genius in disguise. It is not long before Robert Langdon discovers he is being hunted: by both a dangerous hired assassin, his government and mysterious dreams a mountain of human bodies rotting in Dante’s iconic hell. Symbolically, Langdon has the duty of being someone’s Virgil on a journey that could lead to the discovery of a dangerous virus that threatens life on Earth, or its activation.

Langdon is in possession of a mysterious code that he does not take long to decipher. Together with Sienna Brooks he runs through the streets of Florence using famous works of art and Dante’s poetic lines as a guide. As is often the case with Dan Brown, there are many details that make the plot and one can only be too cautious of spoiling the fun for the readers of this journey. The virus they are looking for was planted by a Swiss biologist, an expert in his field, who believes that an increase in population at the current rate will lead to a health pandemonium and the explosion of the worst survival instincts amongst humans. His solution is draconian: a virus that could possibly kill millions.

Beyond the general plot, Dan Brown can be dangerously repetitive. Perhaps in trying to make up for either lack of plot, or because there is so much he wants to show the reader, Inferno suffers from overzealous descriptions of streets, names and places. There is an excess of details pertaining to Dante’s Divine Comedy, or even the existence and description of the Humanity+ movement, who believe that the future of humanity is the genetically modified individual. But the rest of the book can be overbearing, and it reads more like a screenplay, rather than a novel. Though the book is generally fast-paced, it can also be stagnant at times and the reader might feel trapped in a circle of step-by-step actions that are unnecessary.

It is obvious that Inferno tries to be controversial, as Dan Brown has proven single-handedly that if you want to make it big in contemporary literature, a compelling story is sometimes not enough. The reader can rely on Dan Brown to create a fast-paced adventure that will leave the reader breathless to know what happens next. But global health specialists and even amateur statisticians will be perplexed and even outraged at the fact that Dan Brown apparently only read about world population growth theory up to to 2010. A considerable amount of his book, beyond the references and the usage of The Divine Comedy and Renaissance art, relies on the idea that the population growth at the current rate can be dangerous for the future and well-being of Earth and its population. Dan Brown is certainly right about certain aspect of world-population. In most of Sub-Saharan Africa, the attempts of the World Health Organization to stop population growth have been thwarted by religion and culture. The same is true for India, and some of South Asia. Nevertheless, on the whole, now that the world has reached 7 billion people, the rate of growth has steadily declined. The world faces a rapidly aging population and most countries, including China, are well below the recommended fertility rate for a healthy population.

The dangers of an aging population and the gap between developed and developing countries are both health-related and economic. But they are not the ones the ones that Brown describes, and nor do they require the actions that he tries to justify. It is very unlikely that in the near future the world will see piles of human bodies rotting in the middle of Florence, or elsewhere, for the lack of food and because of terrifying disease. What we might experience is economic decline due to the collapse of the current pension and social security system in various nations, but even that is dubious. Nevertheless, Dan Brown can be forgiven-provided the reader remembers that he deals strictly with fiction, not fact.

Whoever reads Dan Brown might be surprised to find him or herself stopping to think over real-world issues that confront us at every turn, but which we prefer to ignore. Nevertheless, the average reader chooses Dan Brown over another for purely hedonistic reasons: because she or he relishes the mental escape and knows that it will be done quickly, leaving the reader to return to an equally fast-paced, though not as dangerous, life. We can safely presume that Dan Brown is not the Goethe, Balzac, or the Hemingway of our era. He is for long-flights, sleepless nights and binge-reading. But there are certainly moments when he can make you think. The issues he grapples with might be either too cliche, or entirely too big for him to handle. Still, Dan Brown creates a compelling story and plot, and though he might not be everyone’s cup of tea, to dismiss him and his works as redundant and cheap, would be to give up on a kind of literature that is for pleasure, just as much as it is about cultural enrichment.

Photo credit: commons.wikimedia.org