With estimates ranging from one to three million total deaths, the Vietnam War spawned some of the most ferocious domestic resistance to government policy to ever exist in the United States. This sentiment was strongly reflected in protest music, which gained significant popularity in the ’60s and ’70s. While the public often views Vietnam as the apex of American protest music, the use of songs to convey political discontent is a long-practiced tradition in the United States. Although early technological and governmental restrictions prevented the voice of the average civilian from being heard, almost every American conflict has inspired musical dissent in one form or another. These songs have evolved over the years as new voices have found the right to share their thoughts.

Censored Beginnings

During the Revolutionary period, music was spread primarily through the print media; therefore, it was tightly controlled by the social elites of the time. Songs were written by well-educated individuals whereas common folk, the ones most affected by war and thus the ones most likely to argue for peace, didn’t have a public voice. Thus, the vast majority of protest songs from this era followed a propaganda-like style.

This perspective is epitomized by tunes like “To Britain,” a song originally published in The Craftsman’s Journal and then redistributed by a number of other American newspapers. It opens with the line “Blush Britain! Blush at thy inglorious war!” Its purpose is twofold. First, the song explains the mires of armed conflict, and second, it blames the fighting on the British. A similar tune, “The Rebels,” was written by Captain Smyth of the British Army; it has a very similar message but shifts blame for the destruction of war towards the colonists. Although both songs could be considered propaganda since they were written by army elites, they also reflected the anti-war sentiment relatable to much of the populace.

The American Civil War saw a slight weakening in the monopoly of speech. While protests against the conflict were common in border states like Ohio, few, if any protest songs were disseminated. This means that either they weren’t written in the first place, or they were censored by the wartime press. The Ohio History Connection, a nonprofit dedicated to preserving the heritage of the Buckeye State, explains on its website that Ohio was home to many “Peace Democrats.” These politically-minded Northerners “strenuously objected to the American Civil War,” usually because they had ties to the Confederacy but also due to pacifist ideologies or opposition to the draft. According to the OHC, many of these Peace Democrats were silenced under General Order No. 38, which stated, “The habit of declaring sympathy for the enemy will not be allowed in this department.” Violations of the order could be punishable by death. This hostile climate made expressing dissent difficult.

For this reason, most music stuck to one of two themes: patriotism or homesickness. Patriotic songs, like the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “Dixie” were written by professional composers, many of whom never saw battle. Despite their popularity, these tunes offered little comfort to those rocked by the horrors of war around them. The average soldier instead tended to embrace ballads about going home. While these songs didn’t protest the war outright, they did covertly express an anti-war sentiment. The song “Lorena” may have been primarily about a Union soldier’s longing to be with his lover, but also reflected a desire for the fighting to end. Even optimistic songs followed a similar theme. “When Johnny Comes Marching Home” and “Better Times are Coming” both focused on the life that soldiers expected to have once the war had ended. These tunes were rarely directly critical of the conflict; Professor Benjamin Tausig of Stony Brook University told the HPR that when it comes to protest songs, “you’re as impolite as you’re allowed to be.” Considering the structured lifestyle that Civil War soldiers lived, such songs were the closest things to protest that they had available.

Fighting Back

Anti-war songs as they are known today developed in the United States during the buildup to World War I. Throughout this time, isolationism was the driving force behind American foreign policy and pacifism became a viable political ideology. The advent of photography towards the end of the Civil War forced the nation to come to terms with the reality of the devastation the war caused, leaving a bad taste in the mouths of many Americans. This contributed to an anti-war sentiment that extended from commoners to composers to congressmen. Social elites still held most of the sway in the production of popular music, but for the first time, many began to write songs that directly challenged the concept of war. Isolationist ideals leant commercial success to “I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier,” which, as Mariana Whitmer stated in the Organization of American Historians’ Magazine of History, was “one of the first songs to protest war.”

Following the Dust Bowl in the 1930s, America saw its first folk revolution. The widespread distribution of record players and radios allowed significantly more musicians to make their voices heard. During this time, artists like Woody Guthrie and Lead Belly wrote a number of politically charged tunes. Carol Oja, chair of the Harvard University Music Department, informed the HPR that the Composer’s Collective, a group of famous composers active in the 1930s, wrote “politically charged and politically informed compositions.” According to Oja, “Times changed, issues changed, and these singers and composers just rose to meet whatever the challenge was.” While their primary focus was not on war, “one [movement] built on another.” Many subsequent artists would look back at this era as the beginning of protest music’s popularization.

After the attacks on Pearl Harbor, World War II avoided widespread criticism. In Music of the World War II Era by William and Nancy Young, the conflict is described as “’the Good War,’ one that few Americans challenged in any way.” Most agreed that a military response was necessary; therefore, few questioned proposals to heavily regulate the music industry. According to the Youngs, 1942 saw the creation of the Office of War Information, which was founded “in an effort to maintain public morale and control the flow of information about the war.” This propaganda agency spawned a spinoff department called the National Wartime Music Committee. The NWMC was tasked with “[evaluating] the suitability of certain songs over others.” As a result of “the heavy hand of government [in] the music business,” most songs went back to the Civil War approach of expressing a longing for home. Melodies such as “I’ll Be Home for Christmas,” “When the Lights Go On Again,” and “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree” spread rapidly among lonely servicemen.

Rebels with a Cause

By the 1950s, the anti-war movement—and thus anti-war music—regained popularity. With the advent of television, the horrors of war could be brought straight into the American living room. As people back home came to grips with the violence and destruction they saw, they began to question the nation’s motivations.

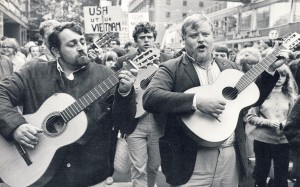

Tausig attributes the reemergence of protest movements to the rise of the baby boomers. There was a “far larger pool [of protestors] than at any other [point] in history,” Tausig explained. Simultaneously, there was a general feeling that young people wanted “to change the world, [and] the Vietnam War became a rallying point for [that] energy.” The mobilization of the nation’s youth, combined with staggering death tolls and unexpected mission creep helped to turn Americans against the war. When the second folk revolution began in the early ’60s, the powder keg was lit.

As young people gained the right to vote under the 26th Amendment, they began to be courted by singers travelling the college circuit. Humorous songs like “The Draft Dodger’s Rag” helped to make the protest movement more mainstream. Moderate entertainers like Simon and Garfunkel and Johnny Cash covered anti-war songs. Perhaps most important of all, the Civil and Women’s Rights Movements brought previously unheard voices into the national discussion. Black artists like Edwin Starr, Jimi Hendrix, and many more took to the stage alongside their white counterparts, united in their desire to end the war in Vietnam. The borrowing and revision of several Civil Rights ballads helped the movement to attract a number of already organized progressives. This coalescence of youthful exuberance and free speech helped to define the 1960s as the decade of disobedience.

The legacy of Vietnam carried over well into America’s future. During the ’80s metal and hard rock bands like Megadeath, Iron Maiden, Metallica, and Black Sabbath exploded in popularity, bringing along a number of anti-war songs. Pop music, on the other hand, was shaped in a different way. According to Tausig, mainstream protest music “became commercialized” at this time, allowing for musicians to raise significant amounts of money for specific causes. “A lot of the mass music for change concerts that took place in the ’80s were modeled after protest music,” Tausig explained. While some genres continued with the anti-war traditions established during Vietnam, mainstream protest music “began to focus on other causes, like curing AIDs and fighting hunger.” In 1986, the golden age of rap began, popularizing protest songs among an even wider demographic. Punk, too, gained popularity, although neither genre became well known for anti-war songs until the turn of the century.

War once again became a primary issue addressed by protest music during George W. Bush’s presidency. The level of protest music being produced was nothing compared to Vietnam, as anti-war tunes were considered a sort of niche, but the U.S. invasion of Iraq still met harsh criticism. In fact, callousness is perhaps the most defining aspect of this era’s music. Green Day, Bright Eyes, and a returning Neil Young all wrote biting tunes directed at the president himself. The U.S. government met new levels of hostility; it is unclear whether this was caused by increasing partisanship or simply by a greater level of openness on the political stage. Either way, Iraq and Afghanistan helped to prove that the 21st century could be one in which Americans are free to express discontent.

Although the scope and style of protest music has changed since the United States’ inception, the very conflicts that have inspired these songs have become more and more rare. Steven Pinker, professor of psychology at Harvard, explained in an interview with the BBC that humanity is currently enjoying its most peaceful era in all of recorded history. As protest songs have declined in popularity, music advocating for social change has risen to the top of the charts. Fifty years ago, Macklemore’s “Same Love” might have been scrapped for a song about nuclear non-proliferation and Meghan Trainor’s body-loving “All About that Bass,” probably wouldn’t have received international attention in a society worried about immediate obliteration. Although music has not always reflected the ideas of the majority, it has quickly become an engrained part of American political culture. So long as every member of society continues to be allowed to contribute to the Great American Songbook, protest music will keep reflecting the trials and tribulations of the times.

Image source: Google Images