“Dear Non-American Black, when you make the choice to come to America, you become black. Stop arguing. Stop saying I’m Jamaican or I’m Ghanaian. America doesn’t care.” – Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, Americanah.

***

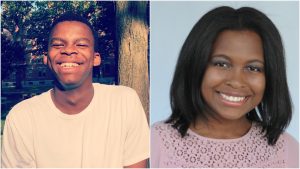

Accepting Adichie’s words has become more than a choice. It has become a frank requirement to understand the black social fabric of the United States. My name is Mfundo Radebe.

“You DON’T belong here.” These words turned what was a very tranquil sunny day in Cambridge completely upside down as everybody tried to understand what was going on. I was confused. I turned to locate where the words had come from and the harsh voice punctuated the air once again: “Go back to your country!” As a black student from South Africa, this clearly had to be me. But I realized that things were now different. I was in America.

My heart was beating faster than ever until the white woman ahead clarified her statement. The white lady somehow felt justified that the Muslim woman in a niqab she screamed these words to did not belong in her America. Immediately, the danger of a single story that Adichie articulated seemed so blatantly obvious. I feared that just as much as this woman could be reduced to a single identity that fit the society she was in, so too could I.

That was September 2016. Harvard has a collection of orientation programs meant to familiarize us freshmen with life in college. This was fundamentally important to me because of the society that I come from, and because coming to America was an indescribably significant cultural adjustment.

I have always had to try and understand how race affects my interactions with society. I grew up in a country trying to rebuild its social fabric after the apartheid period of legislated segregation. In South Africa, identity politics are inseparable from the way society functions. Political parties use them to divide or to unite. Racial context matters. And that is why that raging white voice in Harvard Square confused me. I was ready to own the prejudiced statement as though I was born to take it. It was at that moment that I recognized the need to join an organization that would understand the nuances that come with being black in the United States.

It’s October 2016. Black Mens’ Forum is inviting male-identifying members of the black community to be initiated into this community that can be correctly described as a ‘brotherhood’. I marvel at the mystique this organization has. Its logo, boldly displaying the red, black and green pan-African colors, tantalizes my inherent need to belong with the African polity.

A couple of weeks before, the organization had invited male-identifying members of the black community to be initiated into this community that can be correctly described as a ‘brotherhood’. I marveled at the mystique of the organization. Its logo, boldly displaying the red, black and green pan-African colors, tantalized my inherent need to belong with the African polity.

When I arrived at the appointed meeting place, I suddenly found myself at a standstill. Other new ‘initiates’ were standing in an organized line, quiet and waiting for the next instruction. We were told to be silent, and to march to one of the houses where the event would be held. Our strides along the road were met by onlookers observing and curious as to what we were doing. We passed a few black men. They nodded a simple approval of the gentlemen that were in front of them. Perhaps, it was retribution for decades of the perpetuated notion that black men in this country cannot be orderly. But, to me, this activity could not align with any sense of retribution or liberation. In South Africa, telling black men to march in a line re-awakens the memories of a bitter aid that was used by an oppressive minority white government that sought to control a black majority. They did so with guns and a trigger-happy police force. Our march was, to me, inappropriate.

My identity was no longer framed in the dichotomous white versus black of South Africa. Within the black community of the United States, my own identity was in itself vulnerable. I began asking myself whether was I black enough. And for many of us who identify as black Africans, or even those who are first-generation African Americans, we feel excluded.

This draws me to a conversation I had with Hakeem Angulu, an intern at the Harvard Foundation for Intercultural and Race Relations. According to Hakeem, “the black experience [in the United States] is geared to the African American singular experience”. Hakeem believes that “that is not necessarily a bad thing as it can be historically attributed to the way in which the African-American experience in the country has had to draw itself together as the ‘singular black experience.’” As he gestured with air quotations to pause and ponder this sensitive topic, Hakeem remarked that there is a need “to recognize that there are people such as Marcus Garvey who are not necessarily ‘African American’” and have “also contributed to the black experience in this country.”

Hakeem is Jamaican. “It’s a different experience for everyone, and not just separating African-Americans, from Afro-Caribbeans, from Africans.” I could see the same internal conflict I had gone through surfacing within Hakeem as well.

***

You’re not the only one, Mfundo. My name is Kemi Akenzua, and I would like to share my experience as well.

When I was six years old, I began a new school, in a new Sherman Oaks. At that age, I could not internalize much, but I did notice that in a grade with just under 40 kids, I was the only black student. It was a jarring realization but it didn’t affect my experience and I just thought that no one really noticed.

During the third week of school, I learned that this was not the case. While lining up for our Physical Education class, the classmate behind me scoffed and muttered, “Why do I have to stand next to the black girl?” I froze where I stood and let the words pass through me like a blade. As a 6 year old black girl in this foreign environment, I did not know what to do, so I cried.

Evidently, my experience being black in American schools has been rocky from the start. Comments like the one made to my six-year-old self did not happen again, but microaggressions and ill-thought comments came from my peers and teachers for years thereafter. I, like many black students and people, have had the sly hand reach up and touch my hair, or the stares when the topic of slavery came up, or teachers that asked me to explain to the class what the difference between black and African-American is when I was just 9 years old. These actions did not anger me, but I was always confused by and unprepared for my role as the “designated black person.”

This took a turn, for better or worse, when more students of color came to my school. My status as the only black person changed, but my feelings of isolation did not. As we entered high school, we explored new music, trends, and themes in popular culture. A definition for “being black” emerged for our generation and I did not fit the bill. Things that seemed trivial and inconsequential to me ended up defining my race in the eyes of my peers in high school. I constantly got comments like “wow I’m blacker than you” or “you’re so white.” More often than not, these comments were made because I did not know the lyrics to Drake’s new song, or because I do not know how to “dougie.” The people who decided to jokingly question my race and identity were from all backgrounds and ethnicities. I went from being a foreign entity with odd hair and an odd name, to a sell-out that didn’t embrace my culture. Perhaps the most egregious part of it all was that I did nothing to combat these ignorant comments. Instead I laughed and changed the subject, and I tried to conform by asking my friends for their playlists or dance lessons. Perhaps I did become a sell-out. Not because I didn’t know the music or the trends of black culture at my school, but because I was too scared to fight back.

Now I’m in college. The comments and the occasional feelings of inadequacy have not changed, but the stakes have. I discussed this with my friend Maya Em, a freshman at Columbia University from Los Angeles. She viewed her experience with blackness thus far as complicated, especially in college, as she struggled to surmount the fear of “being called out or told that [she’s] an Oreo.” This is an experience that too many black students have had on campuses and it often creates stark division in the black community when support and unity is needed most. As Maya elaborated, many black students are coming from high school into college “tackling multiple identities of being the token, as well as the exception, as well as the sell-out.” While these terms alone are not inherently bad, they are perpetuated by society and coalesce to create a divisive, and often competitive, nature within the black community.

The final, and perhaps most important topic we discussed was the need to sit back and listen when other black students describe an experience, or belief that you may not recognize or share. Maya recounted her first meeting with the African Students Association, as a liaison for the Black Students Organization, and realized that this was one of the first “black environments where [she] felt like [she] should sit back and listen” to the students who face many of the same challenges but have such different backgrounds and interpretations of “blackness.”

***

“So for example, people will say, ‘Oh, you’re so easy to get along with.’ And they’ll tell me some story of some African-American woman they knew who just wasn’t like me. Which I find quite absurd.” — Adichie in an interview with NPR

We think that historically, blackness in this country has been constantly on defense and has never had the space to breathe and to reflect on its own internal diversity. We turned to Hakeem once again, seeking that confirmation. “It’s this one thing that we all share … it is our blackness. I still don’t know what that means,” he reflected. It seems to us that a full recognition of the nuances of black identity, of what it is to us, will be a long process. It will be prolonged because, as Adichie alludes to, we have to withdraw back to the defensive but proudly affirmative ‘I am black’ in a society that seeks to see us divided.

Image Credit: Mfundo Radebe and Kemi Akenzua