North Korean agent Park Mu-young scans the downtown high-rises and bustling crowds of Seoul. His hair is long, his face worn from years of bitterness. In an eerily calm voice, he says into his phone, “Slow down, friend. The first one is on the roof of the Golden Tower. You have exactly thirty minutes.” The screen flashes to South Korean intelligence headquarters, its clean-shaven employees in black suits. South Korean agent Yu Jong-won stands, frozen. Park continues, “You know the fish named shiri? It’s a Korean aboriginal fish living in crystal streams. Though they’re separated with the country divided, someday they’ll reunite in the same streams.”

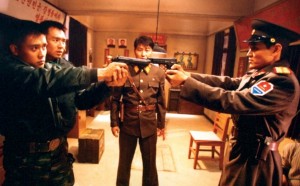

The above scene is from the South Korean blockbuster Shiri. Released in 1999, the suspenseful action film follows South Korean intelligence agents’ heroic efforts to stop North Korean terrorists, especially the elusive female sniper Lee Bang-hee. With over 6.5 million viewers, Shiri sank Titanic’s previous box office record for the most-seen film in the country. Shiri’s success arose from a confluence of factors, including the rise of financial support for cinema from chaebol—South Korean family-led business conglomerates—and the adoption of Hollywood action movie techniques.

Drawing on persistent nationalistic sentiment in South Korea, Shiri directly addresses contemporary political issues facing the two Koreas. These issues—reunification, North Korea’s ballistic missile testing, and the economic disparities between North and South Korea—remain critical to relations between the countries today, and cinema continues to foster public discussion of these divisive topics. Moreover, with the 2014 hacking attacks in response to Sony’s fictional satire The Interview, it is clearer than ever that North Korea’s representation in cinema is redirecting world politics in return.

Shiri Syndrome

Shiri was released just after South Korean cinema broke free from the chains of censorship. Korean cinema censorship dates back to Japanese colonial rule, which banned films that undermined the Japanese empire or its image beginning in 1922. Restrictions continued after the independence and division of Korea with the 1962 South Korean Motion Picture Law, which instituted compulsory government approval prior to the production or exportation of films. While the law was revised over the following decades with intentions to mitigate the effects of censorship, there was little practical effect. Only in 1996 did the South Korean Constitutional Court finally make its landmark ruling that the existing film pre-deliberation system was unconstitutional. A rating system was instituted through an amendment of the Film Promotion Law, with revisions expanding freedoms continuing until 2001.

With government quotas and censorship of South Korean cinema out of the way, the production of South Korean films burgeoned. Shiri rode the tide of the newfound freedom of expression, and its success led to its elevation to what many considered the pinnacle of South Korean filmmaking at the time. Scores of blockbusters were produced in the following years, including Joint Security Area (2001), Friend (2001), Silmido (2003), and Taegukgi (2004). Each broke the previous’ record for sales. This outpouring of films was a result of what has been termed “Shiri syndrome”: the incredibly rapid outflow of blockbusters inspired by Shiri. Shiri syndrome has since spiraled into what is known as Hallyu, or the Korean Wave: the rise of Korean influence in global popular culture, especially in cinema and music.

In addition to its Hollywood-inspired production techniques, Shiri’s manner of addressing political issues inspired and informed the plotlines of many of the South Korean action movies that followed. For example, Joint Security Area also focuses on military and intelligence conflicts between North and South Korea. But more importantly, Shiri transformed attitudes toward North Korea as the “other” in these works. In the era of South Korean cinema censorship, films typically demonized North Korea by portraying the country as a terrorist force plotting to destroy South Korea without reason.

Residues of this deeply entrenched perspective were clearly visible in Shiri, with North Korea entirely harboring the blame for the deaths that resulted from terrorist acts on South Korea. For instance, when South Korean intelligence officers in the film meet to respond to North Korean terrorist threats on well-known locations throughout Seoul, one officer pipes up with naïve incredulity, “But why would North Korea do that in a time of reconciliation?” South Koreans are portrayed as righteous survivors, unable to even comprehend why North Koreans would make terrorist threats against them. The blame, it seems, is directed wholly at North Korea.

Sunshine on the 38th Parallel

Shiri nevertheless initiated an unprecedented humanization of North Koreans as the “other” in South Korean cinema. In Shiri, the North Korean sniper Lee Bang-hee draws in the male protagonist, a South Korean agent, just as she draws in the audience. While she is a villain who is instrumental in a plot to kill thousands of innocent people, we can’t help but empathize with her all the same. These star-crossed lovers come to represent the countries of North and South Korea, symbolized by kissing gourami fish. “If one of them dies, the other dies, too … they dry up from loneliness.”

In Joint Security Area, the North Korean “other” finally receives a personality. Joint Security Area no longer portrays the deaths of North Korean terrorists as a triumph, and the North Korean soldiers have character traits besides pure ruthlessness. We learn that solider Oh Kyung-pil has a great sense of humor, a zest for South Korean snacks, and an unwavering loyalty to his friends, even sacrificing his life for a South Korean soldier. In Shiri, on the other hand, the closest glimpse we get of the personality of a North Korean is of Agent Hee, but even her love for her husband is overwhelmed by her sense of duty to North Korea. These South Korean films humanize the North Korean “other” in order to develop more convincing narratives, but are nevertheless forced by nationalistic incentives to continue antagonizing them as the enemy.

More than expressing a mere willingness to consider the issue of reunification, Shiri hints at a deeper yearning for the nations to reunite. Yet this push towards reconciliation is qualified by an implicit criticism of North Korea’s tactics in attempting to achieve such reconciliation. For instance, North Korean agent Park declares, “This will be the graveyard for the corrupt politicians.” Agent Yu, in turn, counters, “There were people who thought the same as you in 1950. Remember the pain the war caused in this country.” This latter declaration from the film’s hero suggests that, unless North Korea ceases its terrorist threats, there is no hope for the two countries to reconcile. They will instead remain like kissing gourami separated from the waters they once shared.

The attitude toward North Korea portrayed in the films closely aligns with the tenets of the Sunshine Policy instituted in 1998 by South Korean president Kim Dae-jung. It was also remarkably prescient of the issues that would eventually lead to the policy’s end. Under the Sunshine Policy, South Korea maintained a favorable diplomatic stance toward the North for nearly ten years, extending aid and embarking on initiatives such as joint industrial projects and reuniting Koreans separated during the Korean War. Similarly, the South Koreans in Shiri advocate for peace and are, in general, receptive toward the idea of reunification with North Korea. Unfortunately, with the resumption of North Korean nuclear weapons testing in 2006 and little reciprocation of the billions of dollars in aid given to the North, South Korea was compelled to end its Sunshine Policy. Seoul chose to adopt a tougher stance toward North Korea under president Lee Myung-bak, and its cinematic portrayal of North Korea followed suit.

North Korea Returns the Gaze

During Hallyu, South Korean cinema continued to reflect contemporary sociopolitical issues while coming to the forefront of the public gaze. The Korean Wave spurred the production of a flood of South Korean television dramas, or K-dramas, and the gaze on Korean pop culture shifted from national to global. One recent television drama in particular, IRIS, was written as a spinoff of Shiri and aired from 2009 to 2013. In IRIS, North Korea no longer shoulders the entirety of the blame. Instead, an independent organization operating within both Koreas, IRIS, is the terrorist organization that must be stopped by Korean National Security Service agents.

The presence of an outside organization inflicting terror on both Koreas in IRIS is an important departure from Shiri, but the theme of reunification remains central to the series. In the end, it is IRIS that nearly thwarts the continuation of reunification talks between North and South Korea. This reflects the increasingly global political landscape of the conflict between the two Koreas. For instance, the North Korean threat of nuclear attacks in the 2013 Korean crisis was not limited only to South Korea, but also included threats toward Japan and the United States. Tensions between the United States and North Korea have recently escalated, while North and South Korea edge toward higher-level talks. For the first time in December 2014, the United Nations Security Council moved to examine human rights in North Korea, opposed only by Russia and China. North Korea has become the “other” not just to a South Korean, but a global audience.

The North Korean government is particularly wary of the strong influence that anti-communist nations may exert on its people. North Koreans, especially the younger generation, are curious enough about the outside world to be willing to risk their lives and already-limited freedoms to learn more about it. Park Yeon-mi, a former North Korean prisoner who escaped in 2007, related to The Guardian that “if you were caught with a Bollywood or Russian movie you were sent to prison for three years, but if it was South Korean or American you were executed.” Despite these harsh consequences, a black market of smuggled movies and television shows exists in North Korea and has been developing rapidly. While the world scrutinizes North Korea, it gazes back. Their intense interest in the outside world reveals a generation of North Koreans who are not single-mindedly vengeful, like they are portrayed in Shiri, but exactly the opposite: curious and eager to explore humanity outside their borders.

An Unwelcome Interview

The Interview is among the illicit cinematic works being smuggled into North Korea by outside organizations. The film features a portrayal of North Korea’s supreme leader, Kim Jong-un, that exhibits the same conflicted tendencies shown in Shiri. While The Interview tends toward portraying North Korea as the enemy—its plot is centered on assassinating Kim Jong-un—it simultaneously fabricates an Americanized personality that overrides Kim’s cult of personality. Kim Jong-un in The Interview is an uncomfortably relatable caricature who parties lavishly, manipulates ruthlessly, and cries pitifully when he hears Katy Perry songs.

By exposing this side of Kim Jong-un, The Interview’s Dave Skylark (James Franco) dismantles the conception of Kim Jong-un as a deity. He becomes disillusioned with Kim Jong-un and with the North Korea carefully presented to him by the government. In doing so, he highlights North Korea’s flaws. For instance, Skylark goes off on a short rampage about the fake supermarket food he is presented with in Pyongyang, which mirrors the fact that 2.8 million North Koreans faces food shortages, according to a 2012 estimate by Human Rights Watch. The striking truths at the heart of the satire have proved to be dangerous, sparking political response on a global scale, including the hacking attacks on Sony and formal rebukes from North Korean government spokespeople and the government-sponsored media.

Films like The Interview diverge significantly from those that were at the forefront of the Korean Wave. Joint Security Area, for example, exhibited such a positive outlook toward North Korea that South Korean president Roh Moh-hyun presented a DVD copy of the movie to Kim Jong-il in 2007 as a gift. By contrast, cinema portrayals of North Korea today hold the power to forestall peace talks between the two Koreas. No longer simply a reflection of South Korean political attitudes toward North Koreans, the North Korean “other” in cinema today is a global entity.

In humanizing the North Korean “other,” cinema portrayals of North Korea now have the power to offend because of their ability to instantaneously reach a global audience. From its beginnings as a strictly demonized entity within South Korean cinema, the North Korean “other” on film is now being interpreted by North Korea as if it were North Korea itself. And, as North Korea becomes more aware of unceremonious portrayals of its people and leaders in cinema, it takes critiques on film to be attacks in reality. North Korea may think it “didn’t start the fire” because the satire targeted them first. But in reality, North Korea is fighting art with politics. While the newfound power behind cinema portrayals of North Korea carries consequences with it, it also brings a new dimension to the politics of the North Korean “other” in cinema.

This article has been updated from an earlier version (2/24/15).

Image source: Wikimedia Commons