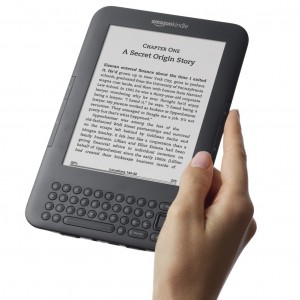

My father was quick to buy the first-generation Kindle. I picked it up off a bookshelf in my dad’s room and marveled. The thin, white, elegant device weighed about the same as each of the 200 books it could contain, their words now converted to ones and zeroes. I knew, even then, that the Kindle was going to change reading for the better.

I think people worry the Kindle will do to books what the iPod did to music. Would carrying around a hardback start to feel as ridiculous as carrying around a portable CD player? The death of my CD player did not cause as much grief as the iPod produced the same sound in a sleeker package. The Kindle, on the other hand, mechanizes reading. The experiences of balancing the spine of a book and flipping through pages are not replicable with a Kindle. Despite the sentimental attachment to physical books, e-book readers provide a powerful advantage of flexibility similar to the iPod. One Harvard student, Ian Anderson ’13 describes his conversion to using his iPad for textbooks and note taking, “The benefits just outweigh the downsides. Sometimes I wish I had the hard copy, since there’s something about the physical copy of a textbook that a screen can’t replace. But the portability is awesome and there are also a bunch of apps that enhance note taking.”

The textbook market recognizes that Anderson is not alone in preferring the convenience and have reduced the cost of textbooks on the iPad. Companies such as Kno, a web-based textbook retailer, have led the way towards offering e-textbooks. Other major players, such as Barnes & Noble, have also started trying to edge into the e-textbook market. The textbook highlights the battle between the cost and weight of hard copy against the drawbacks of reading off a screen.

In general, booksellers have chosen to invest in the technology that would have otherwise put them under. Independent bookstores have been hit hard as one in five bookstores have closed in the last two years. Booksellers have recognized consumers will continue to buy e-readers, and are combating Amazon by creating their own ways of selling e-books.

Barnes & Noble, the largest book retailer in the United States, is combating the threat of e-readers with its own e-reader, the Nook. Barnes & Noble’s Nook tablet and e-reader line controls 13 percent of the market.

For smaller, independent bookstores, the solution has been to sell e-books for all devices. Local indie bookstore, The Harvard Bookstore, will begin a big selling push of e-books soon. Marketing Manager Rachel Cass said, “After we’re done training staff, we’re going to make a big marketing effort to make our customers aware that we sell e-books. We hope that our customers recognize we provide them with a place to browse and buy hardcopy, and feel loyalty to buy e-books through us rather than through alternate sources.” Since publishers standardize the price of their e-books, the Harvard Bookstore just needs to make its customers aware of its offer.

Though e-readers damage and challenge retailers, they also offer immense possibilities for new writers. The e-reader market has spawned numerous new writers who cater to exclusively online markets. Since the bar to publishing a digital book is so low since costs associated with printing and paying publishers are largely removed, independent writers have been able to draw an audience. Harvard Freshman Ben Martin said that although he still values the printed book. But he also added, “I think my Kindle has allowed me to read a lot more and more conveniently than I would otherwise be able to. Also the ability to access public domain books for free has definitely exposed me to some classics that I probably would never have bought or rented in print.” For the adventurous and avid reader and the emerging writer, the e-reader is an empowering device.

And ultimately, the fact that e-readers grant greater access to readers, thereby encouraging greater literary consumption (without great environmental impact), may be the most rewarding feature. People buy e-readers because they want to read more. Whether an e-reader allows them to read on a plane or just buy more books, greater access to literature has never been a bad thing in my mind. That a survey conducted by the National Foundation for the Arts found half of people aged 18 to 24 read no books for pleasure confirms that e-reader trendiness isn’t a bad thing. I am going utilitarian: if more books are being read, it shouldn’t matter if it means fewer physical copies are being sold.