2011 is a year of many anniversaries, both somber and joyous. While Harvard will celebrate its 375th anniversary on October 14, earlier this year marked the 150th anniversary of the Civil War. The beginning of the Confederacy itself actually took place on December 20, 1860, with South Carolina’s Ordinance of Secession. But those first shots, fired at Fort Sumter, began on April 12, 1861. Over the past year, the New York Times has produced a series of blog posts, “Disunion,” which highlights oftentimes lesser-known episodes of the build-up to secession and the beginning of the war. As a history buff, I have greatly enjoyed these articles, and it inspired me to look at Harvard’s own history in the Civil War. Most Harvard students likely realize the somber importance of Memorial Hall, dedicated to the Harvard alumni and students who died to preserve the Union, but her complex history with all sides in the Civil War are more obscure.

Over the next few weeks, to coincide with Harvard’s 375th anniversary celebration, I will release posts on the history of abolitionism at Harvard and the exploits of the Harvard Regiment, but this post is focused on the Harvard men who fought for the South. While the schools that would make up the Ivy League may not have had the same proportional level of national prestige as they do now, Harvard, along with its peers, attracted many Southerners. As a Princeton alumni review of its own Confederate history notes, Princeton was nicknamed the “Southern Ivy.” Southerners by the 1800s made up close to a majority of students. John C. Breckinridge, who would go from Vice President to presidential candidate for the Southern Democrats before accepting a commission as a general of the Confederate Army, attended Princeton (it might seem strange that a former Vice President would later rise in arms against the United States, but even former president John Tyler himself won office as a representative in the Confederate Congress).

Yale, despite being further up north, was not immune to Southern sympathy. In Disunion, the Times highlighted an episode at Yale, when some students (it is unclear if they were simply pranksters or budding Confederates) hoisted the “secession flag” of South Carolina over a building. Another Bulldog, Judah P. Benjamin, would go from Senator of Louisiana to stints as Confederate Secretary of War and Secretary of State. In one historical irony of the Civil War, the Confederacy would appoint a Jewish cabinet member 40 years before Oscar Straus became Secretary of Commerce and Labor in 1906. And in regards to the University of Pennsylvania, even my great-great-grandfather, Zimri Smith Coffin, received medical training at Penn before serving as a quartermaster and militia officer for North Carolina.

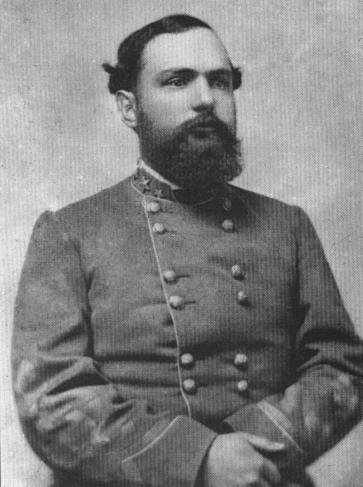

And what of Fair Harvard? As with Yale, the far northern location of Harvard, along with the abolitionist tendency of Boston, deterred Southerners from enrolling at a level such as at Princeton. Nevertheless, Harvard provided her share of troops and officers to the Confederacy. Helen Trimpi, in her work Crimson Confederates, built upon existing documentation of Confederate Harvardians to compile biographies of those who fought. In her research, she found that 357 students and alumni fought in the Confederate forces. Of these, 227 attended the Law School, 104 attended the College, 41 attended the Lawrence Scientific School (precursor to SEAS), and 3 attended the Medical School. In addition, 29 alumni served in other capacities in the Confederate government. The Crimson Grays came from all Southern states (Jose Angel Navarro, son of a Tejano revolutionary, was the sole Texan, although he was born when Texas was part of Mexico), a number of Northern states, and even from abroad. Sixty-four of them would die in service, and 15 would become major or brigadier generals. One of the oldest Confederate veterans was Elias Levy Yulee, of the Virgin Islands by birth and a settler of Florida. His brother, David Yulee, earned both the distinction of the first Jewish senator and the first senator from Florida, but he would also serve in the Confederate Congress. A number of other Rebel alumni were often relatives of more famous Confederate leaders. Thomas Semmes, of a distinguished Catholic family of Maryland, was the cousin of Admiral Raphael Semmes. Admiral Semmes gained distinction in the South and infamy in the North for his privateering against Union shipping on the CSS Alabama. Benjamin Huger, Jr., shared his name with his more well-known father, General Benjamin Huger.

Of course, no name is more famous in the South than that of Lee, and in the late 1850s, one of the residents of Massachusetts Hall was none other than William Henry Fitzhugh “Rooney” Lee, son of Robert E. Lee. Rooney Lee’s time at Harvard epitomizes the experience of the elite Southern planter’s son at Harvard, Yale, or Princeton. Mary Bandy Daughtry’s biography of W.H.F. Lee, Gray Cavalier, notes that Rooney’s highest rank at any point in his Harvard career was 56th out of 91 in his year. Despite having a less-than-stellar academic and discipline record, Rooney was quite popular in the social scene. He rowed for the crew team (while President Charles Eliot is generally credited with first wearing red to signify Harvard, Lee family lore insists that Rooney did this first). Rooney Lee also enjoyed membership in the Hasty Pudding and Porcellian Clubs, and his own writings suggest a fondness for good drink and socializing.

Henry Adams was a part of Rooney’s social circle and characterized him as the typical Southern aristocrat at a Northern institution, being “as little fitted for [Harvard] as Sioux Indians to a treadmill.” As Daughtry points out, Rooney in Adams’ eyes was a “simple, kindly, unaffected, modest gentleman.” Rooney ultimately decided that the ivied halls of Harvard was not for him, and thus he left Cambridge in 1857 for a commission in the Army. Of course, Virginia would secede just 3 years later, and Rooney Lee followed his father into service of Virginia and the Confederacy. He became a cavalry officer, ultimately serving under the dashing general J.E.B. Stuart. Rooney, himself rising to the rank of general, would cross the Potomac in the Gettysburg campaign and later serve in the defense of Petersburg and Richmond. During the Gettysburg campaign, Rooney, under “Jeb” Stuart’s command, met a Union force in an engagement, the Battle of Brandy Station, that epitomized the struggle of “brother against brother.” Facing him was the 2nd Massachusetts, “Harvard’s Heroes,” commanded by fellow Harvardian, rower, and Hasty Pudding mate Charles Mudge. Clark Hall recounts how in the fierce fighting, Rooney Lee was seriously wounded. Rooney would go on to survive the war, but Mudge would not.

“Brother against brother” is a common cliche of the Civil War, yet the record of Harvard Confederates confirms the truth of that phrase. Classmates, neighbors, and close friends would exchange the ivied halls and classrooms for the battlefield. For the sixty four Harvardians who died in gray, there has remained the question of whether it is appropriate to note their service. Last year, The Crimson explored the periodic attempts to memorialize Confederate dead. For now, Memorial Hall stands in memory of solely the Union casualties, and the last attempt at a Confederate memorial in the mid 1990s fizzled out. Nevertheless, the service of Harvardians in the Confederacy confirms the extent to which our country was divided by the questions of slavery and secession.