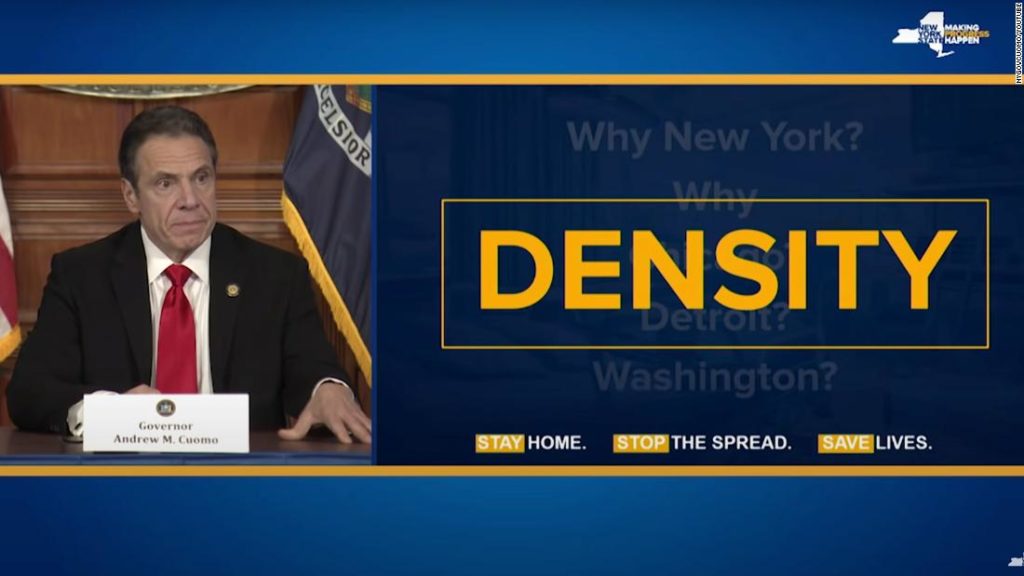

As the coronavirus pandemic has progressed, some have blamed a specific urban culprit for increasing the transmission of the virus: population density. The case of one badly-hit American city, New York, has fueled this layman’s theory of viral transmission. “It’s very simple,” said New York Governor Andrew Cuomo at a press conference. “It’s about density. It’s about the number of people in a small geographic location allowing that virus to spread. … Dense environments are its feeding grounds.” Following New York’s outbreak came a torrent of alarmist op-eds questioning the future of urban America. A Los Angeles Times opinion section headline read, “Angelenos like their single-family sprawl. The coronavirus proves them right.” Meanwhile, a New York Times news headline warned that this negative focus on population density could have real consequences on housing policy and specifically, hinder advocacy for denser housing.

On its face, this logic seems to make sense. When people live closer together, there might be more opportunities for infected people to come into contact with others. But the story is not so simple. The evidence lies even in New York itself — the boroughs of the Bronx and Staten Island each have well over twice the infection rate of Manhattan, the city’s urban center. Manhattan has by far the lowest infection, hospitalization, and death rates in New York City, despite its status as the country’s urban metropolis and a population density over twice that of the Bronx and about nine times that of Staten Island. Clearly, there is a whole lot more than density at play in the spread of coronavirus.

New York Governor Andrew Cuomo presents a slide placing blame for coronavirus spread on density. Source: New York State Office of the Governor.

The most immediate factor explaining these inter-borough differences in New York is the income level and wealth of the populations. Manhattan boasts 3.5 times the average income of the Bronx and over double that of Staten Island. To make matters worse, a Drexel University study in Philadelphia found that people in lower-income neighborhoods have been tested at one-sixth the rate of those in higher-income areas. Socioeconomic status intersects with people’s health and access to health care in countless ways, as is made clear by the fact that New York’s outer boroughs are home to the lower-income essential workers who have been on the front lines during the pandemic, exposed to many more potential carriers of the virus. Coronavirus is transmitted not through the walls of urban dwellers’ neighboring apartments but within the business establishments, hospitals, and other public places that all essential workers — urban, suburban, and rural — must frequent daily.

The racial disparities of coronavirus spread have been well-documented as well. In Michigan, while Black Americans make up only 14% of the population, they comprise 40% of the COVID-19 death toll. The Navajo Nation has reported more coronavirus cases per capita than any state. Essential workers are disproportionately people of color to an overwhelming degree, and this higher risk is compounded by the significantly lower quality of healthcare provided to people of color overall. In addition to a range of socioeconomic disparities, race is therefore playing a key role in influencing individual risk to COVID-19 — proving far more important to understanding the spread of the virus than the density of houses and apartments.

The mismatch between density and infection is not just apparent within New York City. A World Bank study of infection rates across China finds no relationship between population density and coronavirus infection rates. This data from China has the advantage of showing a fuller picture of the virus after a complete outbreak cycle, and it reveals that cities with higher population densities actually had lower infection rates. Infection rate differences between large metro areas, which each include both dense urban centers and sprawling suburbs, are much greater than the differences within them. International comparisons tell a similar story: South Korea, which had its first COVID-19 case on the same day as the United States, has now been surpassed in cases by Iowa alone, despite the dense megacity of Seoul and a population over 16 times Iowa’s with only two-thirds as much land area. This story is repeated in hyper-dense cities like Singapore, Hong Kong and Tokyo. It matters whether you happen to live in a badly-hit region of the country or the world, not whether you live downtown or outside the city.

While there are some features of denser living, namely public transit and proximity to international airports, that may lend themselves to virus transmission, cities are also home to a few advantages that have mitigated the spread of coronavirus. For example, urban areas generally have a much greater capacity to respond to a spike in hospitalizations, while rural America is facing a crisis of distant and inadequate healthcare infrastructure. Rural recreation areas in particular have become major hotspots of coronavirus. As the World Bank study notes, urban areas are also much more abundant in high-speed internet and door-to-door delivery services that allow people to stay connected, fed, and stocked with material goods without having to venture into public spaces.

Still, there are important steps urban areas can take to reduce crowding and improve urban resistance to diseases like COVID-19. Addressing their historic housing shortage would mitigate the overcrowding within housing units has been tied to coronavirus spread in Chicago. Wider sidewalks would create room for pedestrians to spread out and enjoy more of the space that has traditionally been relegated only to car use. In the midst of a pandemic, closing some streets to allow for greater pedestrian and bicycle use, as many cities have begun to do, makes them even more resilient to disease.

Suburban sprawl is not the solution to viral transmission. This increasingly popular idea ignores the reality that disease is predominantly transmitted in the kinds of public spaces common to all levels of population density, and it ignores the data on coronavirus spread. Coronavirus risk is an issue of socioeconomic status and its intersection with the varied response to the outbreak in different communities, making the popular focus on urban density a distraction from the real disparities that expose some people to the disease more than others. To protect themselves from COVID-19, people do not need longer driveways; they need to be able to stay home.

Image Credit: Pixabay / Alan Blatt