For Robert Campbell, the first warning sign was the bookstores leaving. For years, Harvard Square had been a haven for bookstores, but then they began to close one by one, beginning in 1992 with Cambridge Booksmith, and then Reading International, and then Barillari. For Elsa Dorfman, it was the camera stores. “There were at least five camera stores,” Dorfman recalled, “and now there’s one feeble camera store, so that’s a whole category of stores that are gone.” For Paul Macdonald, it was the closing of The Tasty and Wursthaus, two restaurants that had occupied the Read block, where Starbucks and CVS now stand, for decades.

For these and other longtime Harvard Square residents, the Harvard Square that they grew to know and love is gone. That Harvard Square was one where, according to Campbell, “you could go, and for 50 cents — the price of an English muffin and a cup of tea — sit there and argue about Marx all night.” It was one where, according to Macdonald, you could go to The Tasty and “those five stools could have Doc [a well-known resident of the Square], a Nobel Prize-winning professor, a runaway kid, and probably a facilities maintenance worker, and they’re all talking Red Sox.” In Dorfman’s summation, “it was just a town.”

The funny thing about golden eras, of course, is that they are often only golden in retrospect. As J.D. Pollack, the former co-owner of the Brattle Theater, once remarked, “What you love about the Square is how you saw it the first time. That is the way you think it should be, and you are resistant to any other view of it.” Indeed, even in the midst of the Square’s purported ‘golden age,’ there were those decrying its decline from the glory days of yore — a 1973 Crimson article lamented the fact that “retail chains have replaced some of the older smaller storefronts.” Kari Kuezler has noticed this tendency toward excessive sentimentality among Harvard Square residents in the 15 years she has run Grendel’s Den, a restaurant opened in 1971 by her parents. “One of the things that doesn’t change is just the incessant nostalgia that drives this [sentiment that] everything that used to be good is gone,” Kuezler told the HPR.

Nostalgia also lends itself to an exaggerated sense of change. According to Harvard Square Business Association executive director Denise Jillson in an interview with the HPR, roughly 70 percent of businesses in the Square remain locally owned. While many of the unique stores that lined Massachusetts Avenue and Brattle Street when Campbell and Dorfman attended Harvard in the ’50s are gone, many are still here today, including Dickson Bros. Hardware Store, Brattle Square Florist, and the Grolier Poetry Book Shop. Many locally owned businesses have opened in the Square in recent years as well, like Forty Winks and El Jefe’s Taqueria.

Yet rampant fears about the changes happening to the businesses of Harvard Square are not unfounded. Concerns about challenges facing small, locally owned businesses in the Square are valid, but underscoring the advent of national and international chains in the Square is a larger, perhaps more insidious, change: the proliferation of businesses catering to an increasing affluent clientele. “It’s not just what leaves, it’s what comes in and takes its place,” said Macdonald. Cambridge City Councilor Jan Devereux echoed this sentiment in an interview with the HPR: “People from other parts of Cambridge have also always come to Harvard Square because it was interesting, historic, had a wide range of stores, relatively welcoming to people from all walks of life, and so I think some of them are probably feeling less like there’s anything for them there.”

Recent retail additions to the Square bear out Devereux’s claim — this year alone, three new upscale eateries have opened up shop: Blue Bottle Coffee, Pokéworks, and Zambrero. And plans are underway for several more, including a high-end gelato chain, a D.C.-based make-your-own pizza place, and several fast-casual restaurants and bakeries in the renovated Smith Center. Changes to the Square’s business composition show no signs of slowing, begging the questions: Who are these changes for? And what is lost when the affordable shops and restaurants that have historically served the Square disappear?

“The rent is too damn high.”

Club 47 opened on Mt. Auburn Street in 1958, advertising itself as a “jazz coffeehouse.” Over the next decade, it became a Harvard Square institution, offering lively concerts by up-and-coming musicians to students and Square residents. It was, according to Campbell, a place where “someone named Joan Baez was overheard in the crowd one night to be singing louder than everybody else put together.” In 1968, however, citing rising rental costs, Club 47 closed its doors. Club 47’s demise would be a bellwether, albeit an early one, of changes to come.

A quick perusal of Crimson articles on store closings over the past two decades reveals a startling trend. The owners of One Potato, Two Potato, a restaurant that closed in 1996, complained of “skyrocketing rent costs.” Bill Humphreys, the manager of music and electronics store Briggs & Briggs which closed in 1999, told the Crimson, “I would rather continue on elsewhere than stay here and pay the rent and end up going out of business.” Robert Gordon, the president of Store24, a convenience store that closed in 2001, remarked, “The landlord just raised the rent so high that we couldn’t afford to stay.” More recently, the owners of a spate of stores that have closed since 2013 — Tamarind Bay, Bertucci’s, Tommy Doyle’s, Uno Pizzeria and Grill, Schoenhof’s Foreign Books, The Just Crust, and Hair Cuttery — all complained of rising rental costs.

The increase in rental costs in the Square appears to have accelerated in recent years. Between 2012 and 2017, the assessed value of property in the Square almost doubled, from $1.8 billion to $3.2 billion. “We’re in a really competitive market, especially in Harvard,” Adriane Musgrave, the executive director of Cambridge Local First, explained to the HPR. “Everyone really wants to be in Harvard; it’s an international destination.”

The extent to which rising rental costs have disadvantaged small, locally-owned businesses relative to national chains is contested. Musgrave and others argue that, since small businesses have less capital, it is more difficult for them to absorb rent hikes. “It’s a lot harder to compete with a big national chain that comes in with significant, significant financial backing, driven by investors which are not local in many cases,” Musgrave argued. National chains also, Devereux pointed out, don’t necessarily need to make a profit — they “are willing to pay a rent that they can’t really justify based on the sales, but it’s good advertising.” Macdonald worries that potential small business owners will be discouraged from opening up shop because of the high sticker price of a lease. “Maybe a married couple has a great idea, [but] can’t afford to put it into play just because of the rent,” Macdonald said. “Can’t take the chance, you know?”

Others, however, argue that rent is not as much of a problem compared to other, larger-scale changes. Christos Soillis, who has owned Felix Shoe Repair since 1969, points to a declining demand for the product he offers. “Rent doesn’t mean anything. If it was the old days, I can double my rent and I can pay it, because a long time ago, we [could sell] six boxes, bigger than this,” Soillis told the HPR, gesturing to a box of shoes in the store, “and we had Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, boxes of shoes, full.” Furthermore, Soillis’ landlord is Harvard, which is generous in setting a reasonable rent and allowing Soillis flexibility in months when he comes up short. Indeed, Harvard is the largest landowner in the Square, and leases to many of the Square’s most historic businesses, including Leavitt & Peirce Tobacco, which Macdonald owns. In an email statement to the HPR, Harvard spokesperson Brigid O’Rourke wrote, “Through its leasing practices, contributions to improving the public realm, and the support and buying power of its students, faculty and staff, Harvard plays a key role in ensuring that the Square remains both vibrant and dynamic.”

One could even argue that small businesses, even those with less generous landlords than Harvard, are in a better position than national chains to deal with rising rental costs, given broader changes in the economy. Lisa Hemmerle, the economic development director at the City of Cambridge’s Economic Development Division, said the city held a small business summit recently where many experts said that “small businesses are actually in a better position to pivot in this market.” She pointed to struggling large national chains that have had to close up shop in the Square recently, like American Apparel and Radioshack.

Regardless of the impact on small businesses, however, rising rents indisputably have an impact on the affordability of the Square, as businesses are forced to pass on increasing costs to customers. Many new stores and restaurants that have opened in the Square in recent years, whether locally owned or not, carry high-end merchandise or serve upscale food. Even the Square’s new fast food chains cater to a more affluent clientele — it’s not McDonald’s and Burger King that are opening in the Square, but Pokéworks and Sweetgreen.

“We’ve kind of lost our base.”

If the Square’s businesses look different than they did several decades ago, perhaps another reason is that the people patronizing them are different. Over the past several decades, the economic makeup of Cambridge residents has changed dramatically, particularly in Harvard Square. One driver of this change is the demise of rent control, which was abolished in 1994 via a statewide ballot referendum. In the ensuing decade, the value of the city’s housing stock skyrocketed by $1.8 billion, and it has only continued to rise since then.

The more housing costs rise, the more affluent residents have to be to live here. “The demographics of Cambridge have changed pretty radically since rent control ended in 1994,” Devereux said. “So that has taken away a lot of middle class and left us with sort of two ends of the barbell in terms of who our residents are.” Devereux’s claim is backed up by Census data which shows that, while the poverty rate in Cambridge has remained largely unchanged, median household income ballooned from $47,979 in 2000 to $83,122 in 2016, well outpacing inflation.

In Harvard Square, the shift has been even more extreme. According to the city’s Community Development Department, the median household income within a one-mile radius of the Square is a whopping $132,588. With the economic diversity that used to characterize the Square left many of the people who frequented the Square’s old businesses and made life in the Square interesting. “The poets, the writers, the Beatniks, the hippies from the ’60s could afford to live in the outskirts of the Square, and they got rid of rent control,” Macdonald said. “We’ve kind of lost our base of quirky and interesting characters.”

The demographic shift has also manifested itself in an increasing antagonism toward homeless people in Harvard Square. James Shearer has noticed this rising animosity in his capacity as a writer and co-founder of Spare Change News, a newspaper based in the Square that focuses on issues of social justice. “I’ve been in Boston 40 years, and I’ve seen the Square go through a lot of changes, but this is the first time I’ve seen it in a way that really just seems to discourage homeless people from being there,” Shearer said in an interview with the HPR. “The Square’s always seemed more open, and it just seems less so now.”

The changing composition of Cambridge residents is not the only demographic change that has affected the Square’s businesses. Until 1984, Harvard station was the northernmost terminal on the Red Line, which meant the Square was where people from many of Boston’s northern and western suburbs drove to in order to catch the train downtown, and where people transferred from bus to train, or vice versa. This brought a great deal of foot traffic to the Square, and, in turn, a large number of customers from all over Boston to the Square’s businesses. When the Red Line was extended to Alewife, the bus station was moved underground. After this happened, Devereux explained, “people started to realize that, ‘Oh wait, that’s not gonna be great for the stores, either, because people don’t physically have to pass them as they’re changing from train to bus or vice versa.’”

Foot traffic in the Square has by no means suffered, though. This is in large part due to another phenomenon that emerged around the same time that commuters were pushed underground and out to Alewife by the Red Line extension: increasing international tourism. “The number of visitors in the Square has exploded since the 1970s,” said Alex Krieger, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, in an interview with the HPR. Because many international tourists come to see the university itself, rather than the businesses in the Square, their increasing prominence may have an adverse impact on the Square’s small businesses. Tourists, Krieger explained, “may enjoy seeing a unique store or two but actually are also quite comfortable seeing a CVS because they need stuff and are familiar with the establishment.” On top of this, international tourists are, on average, more affluent than the commuters who used to come through the Square, and have more money to spend at the Square’s increasing cadre of high-end boutiques and upscale restaurants.

Follow the Money

The increasing international status of Harvard influences not only tourists but also real estate investors, whose footprint in the Square has grown in recent years. To these investors, the Square is a prestigious, reliable source of income. “Harvard Square has increased in value so rapidly in relation to the rest of the country that it’s a safe bet,” Campbell explained. “You put your money in, take some more out some other day, you make a profit.” Musgrave referred to this practice as “land banking.” “Just like you’ll put money in your savings account, you’ll buy land and you’ll put it in a savings account in a similar way,” Musgrave explained. “You’ll keep it, and wait for it to appreciate, and sell it at multitudes of what it was worth.”

The phenomenon of large real estate firms buying up property in the Square is a relatively new one. Up until recent decades, according to Cambridge Historical Commission executive director Charles Sullivan, most property in the Square was held by real estate trusts, through which families could maintain control of properties for multiple generations. Often, these families were more connected to the Square and invested in maintaining a vibrant, diverse business composition. The Dow family, for example, owned the Abbot building which houses the Curious George Store, as well as several other properties on Brattle Street. “They were maintaining tenants who didn’t necessarily pay the maximum rent but provided services that people liked and wanted, that brought people to the Square,” Sullivan said in an interview with the HPR.

Beginning in the ’90s, however, these trusts began to sell their properties to large real estate investors, who were less invested in the livability of the Square. In 1995, Sullivan said, the Read block was sold by a trust to the Cambridge Savings Bank, whose redevelopment of the property precipitated the closing of The Tasty and Wursthaus. More recently, the Abbot building was sold by the Dow-Stearns trust to Equity One, a Jacksonville-based real estate developer that aims to build a luxury pedestrian mall to replace Urban Outfitters, sparking fears that the Curious George Store would also be forced to close.

Large, non-local real estate investors can be challenging landlords for small businesses and businesses offering affordable products. “Once the goals of the investors change from just a steady, reliable income to wanting to cash big-time, then that’s when the change threatens the tenants,” Sullivan explained. Non-local landlords, according to Devereux, are more likely to pass on tax increases resulting from higher property value assessments to their tenants. Even for businesses with local landlords, the high price these real estate investors are willing to pay to purchase property in the Square has ripple effects. Although Kuezler does not have to worry about rent increases for Grendel’s Den because the store’s rent increases on a schedule, she noticed that Equity One’s purchase of the Abbot building had an effect on her taxes. “The property values kind of ballooned very suddenly because of the purchases a few years ago,” Kuezler said. “And that increased the taxes.”

Beyond forcing longtime tenants out, another concern is that large real estate investors are willing to keep storefronts vacant for long periods of time. They are able to do this, according to Harvard Square Neighborhood Association steering committee member Abra Berkowitz, because they can afford to. “If you can afford to leave your storefront posted at a very, very high rent, then in a way, you might as well, because it’s not like you’re taking a monthly hit by not getting the revenue,” Berkowitz told the HPR.

The impact of this practice is evident in the Square. Although, according to Jillson, the vacancy rate in the Square is only 6 percent, there are several vacant storefronts in highly visible parts of the Square. Devereux pointed out several: the spaces formerly occupied by Crimson Corner, Hidden Sweets, and the Harvard Square Theater. The latter is perhaps the highest-profile vacancy in the Square, and is owned by billionaire real estate investor Gerald Chan, after whose father the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health is named. Chan recently unveiled his plans for the site of the old theater, which include a new theater, as well as retail and office space. Yet it has remained vacant since 2012, and as of yet there is no timeline for the redevelopment project. The billboard on Church Street advertising retail space for lease serves as a painful reminder to some of all of the businesses the Square has lost in recent years. “It was a really big thing that added a lot of energy and activity, and so that’s something that is a shame that we’ve lost.”

The ‘Nouveau-riche Brattle Street’ Cohort

Given the emotional attachment that so many people form to the Square, it is no surprise that a multitude of organizations have arose to defend and preserve it. Yet, in an ironic twist, their efforts to preserve the Square may have only contributed to today’s affordability concerns.

The first major battlefront in the war between preservationists and developers was the original Kennedy Library proposal in 1968, which would have located the library, in addition to a museum and public park, on the site where the Kennedy School of Government stands today. The Neighborhood Ten Association mounted a court challenge against the proposal, arguing that it would bring too much tourism and traffic to the Square. They were successful, and the Kennedy Library was relocated to Dorchester, where it stands today. This battle, according to Campbell, was a major victory for the residents of “the nouveau-riche Brattle Street area,” who “began to have very strong, personal feelings about being against modernism and preserving the historic fabric of the city.”

A decade later, members of the Neighborhood Ten Association who had been active in the fight against the proposed Kennedy Library formed a group called the Harvard Square Defense Fund to negotiate the deal that would bring the Charles Hotel to the Square, successfully reducing the retail space that would go along with the development, increasing housing units, and eliminating the proposed theater. The HSDF “soon became the most powerful community group in the city,” as Sullivan and Susan Maycock wrote in their book Building Old Cambridge.

Yet some argue that the the creation of HSDF and similar organizations led to an overzealous protectionism in the Square that impeded new developments that could have helped in keeping rental costs down. “The constraint on development probably increases the pressure on the landowners to take advantage of higher rents,” Krieger explained, “and so you’re starting to switch to other kinds of retailers as opposed to the kind of mom-and-pop shops that, in theory, the Square was all about a generation ago.” Campbell agrees. “Cambridge … is the most protected city in the country, I’m sure,” he said. “So there’s not a whole lot of opportunity for further redevelopment within the boundaries of Cambridge.”

Yet Berkowitz argues that the protections and regulations on new development advocated for by groups like HSDF and her organization, the Harvard Square Neighborhood Association, which formed out of HSDF, are necessary to preserve the qualities of the Square that make it unique. She conceded that “if you made it less historic and like everywhere else, then maybe it would be less expensive,” but argues that it is the historical aspect of Harvard Square that makes it desirable, and that is worth protecting. Increasing rent costs, Berkowitz contended, is a nationwide phenomenon driven by forces outside of Cambridge. As an example, she pointed to Kendall Square, which despite not having as many development-impeding regulations as Harvard Square, is still seeing skyrocketing rents.

Squared Away

It can be difficult to parse between all of the broad forces, national and local, affecting the business composition of the Square. “There’s not one single villain in this, and it’s not necessarily that anyone is a villain,” Devereux said. “It’s just a whole bunch of different forces that have kind of converged at the same time.”

The vastness of the forces that businesses in the Square selling unique, affordable products are up against can lend itself to a certain resignation. Dorfman, in accounting for the recent changes that the Square has seen, put it simply: “It’s just inevitable.” Yet there are certainly things that can be done to preserve the remaining affordable stores and restaurants in the Square, and to encourage new ones.

When assessing all of the recent changes, Macdonald sees one culprit: money. “That’s what the world revolves around, money,” he explained. “And my goal, I don’t look at it as to make money, I look at it as to keep my customers happy, give them great service and a beautiful environment, and if you do that, you do well. But when money becomes the end, it’s sometimes a recipe for disaster.”

Soillis agrees that a relentless pursuit of money is the culprit. “If I die tomorrow morning, one-time death, I don’t feel anything, but if I get sick, and I’m going to the hospital, I would cry day and night, because I don’t want to leave the Square without support,” Soillis said. “Because the Square, it does need a shoemaker, a shoemaker to believe in what he does, not only to be a thief, to take the money from the customers, to work for the dollar.”

The cover art for this article was created by Brenna Leaver, a student at the Rhode Island School of Design, for the exclusive use of the HPR’s Red Line.

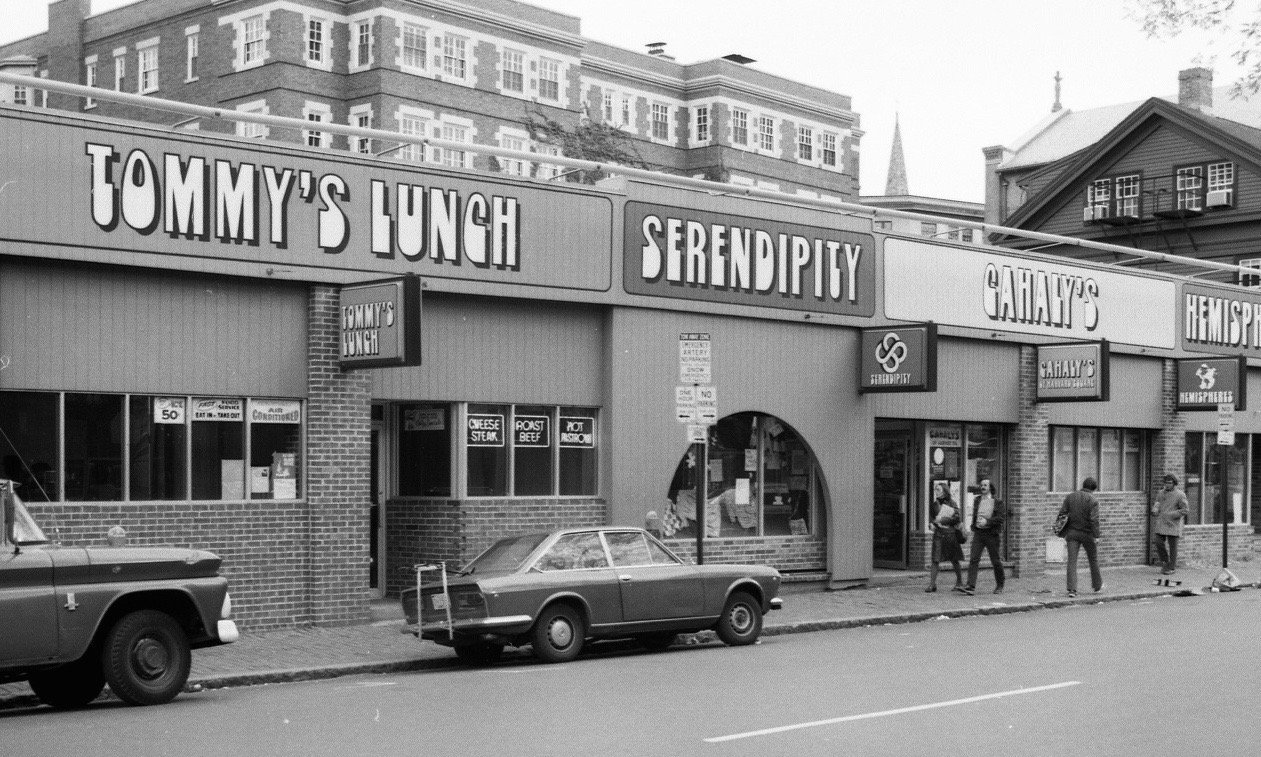

Vintage photographs, taken in the late 1960s, were provided courtesy of the Cambridge Historical Commission. New photographs were taken for comparison by Quinn Mulholland.