In 2010, the city of Port Au Prince, Haiti was racked by a category seven earthquake. The death toll reached 220,000, while 2.3 million individuals were displaced from their homes. With 17 percent of Haitian government officials killed in the earthquake, aid agencies were left to manage municipal responsibilities. Humanitarian aid money poured in, totaling $13.5 billion. Yet, of that amount, only 1 percent of the aid went towards rebuilding the government and 0.4 percent of it to Haitian local NGOs.

Delivering the aid in Port Au Prince presented a whole new challenge. Previous models of humanitarian aid followed the guidelines of the Sphere Standards, a book of instructions on delivering a minimum standard of aid, often in refugee camp settings. In Haiti, the Sphere standards’ rural focus was insufficient to address the influx of displaced individuals into urban slums. The standards also failed to explain how aid should operate in an urban environment, where, unlike in camps, infrastructure and city dynamics were not created or controlled by NGOs. In particular, Sphere specified plots of land and minimum surface areas for affected populations — in urban slums, achieving this standard was impossible due to Haiti’s existing poverty and high urban population density. Haiti was plagued by issues of land ownership, overcrowding, water sanitation issues, and a large unemployment rate. The insufficiencies of the standards were further exacerbated by a lack of coordination and clear priorities. Despite the talk of incorporating Haitian priorities in recovery efforts, Haitians were excluded and international NGOs pursued their own agendas.

Aid for a disaster became a disaster. Though the United Nation was coordinating the international response, there were gaps and redundancies in aid. NGO staffers were often new, inexperienced, and had high turnover. Dr. Michael VanRooyen, the Director of the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative, told the HPR that generally, “the more difficult it is to reach and the more complicated a humanitarian setting is, the fewer organizations will be able to go, and those that arrive are usually the professionals.” These professionals are able to communicate with each other. Haiti was an outlier — the ease of access to the airport and region meant that “anybody with any tie to aid and any interest” could work there. VanRooyen notes that for these inexperienced workers, there were no rules, and the normal coordination mechanisms were unable to deal with the volume of NGOs.

Adding to these issues was the fact that local Haitian NGOs were left out of meetings, creating a skewed set of priorities among many Western responders. Needs were addressed in the short term and only partially: when drainage systems were needed, NGOs merely shored up nearby river banks. When permanent infrastructure reconstruction was needed, CARE and Spanish Red Cross only provided Temporary Shelters that deteriorated. NGOs assisted the poor, but did not make huge strides towards pulling individuals out of poverty.

With NGOs only focusing on immediate needs or beneficiaries, they lost focus of longer-term recovery and the rebuilding of Haitian government capacity. Even a year after the earthquake, many individuals still lived in tents, or rubble remnants of their home wracked by violence. Five years after the earthquake, cholera — which emerged 10 months after the earthquake — remained rampant, killing around 9,000.

Since humanitarians had excluded the decimated government from relief efforts, NGOs faced difficulties in transferring authority back to the Haitian government, which only controlled 23 percent of longer-term aid. The earthquake relief efforts had generated a catch-22: as NGOs had taken over city services completely, the Haitian government fell back on this model instead of bolstering the resilience of its own services. Consequently, humanitarians could not bring themselves to leave. Their interventions had weakened the government so that it was ill-equipped to deal with both the high level of need from the earthquake and from pre-disaster poverty. Ultimately, Haiti never fully resumed responsibility over its affected populations — it devolved into a “NGO Republic,” owing to the lack of collaboration between state and private actors, the fact that humanitarian aid exceeds the country’s budget, and the failure of the international community to respond appropriately to the urban crisis.

As HHI’s VanRooyen noted, Haiti is “a unique and problematic disaster,” where the massive failures that occurred are not the norm for the NGO and humanitarian community. Despite this lack of representativeness, Haiti’s earthquake was a “cataclysmic event” that changed the way the aid world saw itself. Humanitarian actors noticed several aspects about the delivery of aid that needed re-evaluation, while the NGO’s struggles in building city resilience after a long tradition of providing free humanitarian services raised new questions about not just the standard of aid in urban areas, but the conduct of aid as well. The era of the NGO Republic had acquired an expiration date.

The Changing Field of Humanitarian Aid

While war, conflict, natural disasters, and displacement have been consistent fact of history, humanitarian aid agencies now face the daunting task of changing global demographics. Global displacement is the highest it has even been, with 65.6 million individuals displaced, twice the level of displacement in 1997. Of these, 40.3 million displaced people are Internally Displaced Persons, who have not crossed a border, and are therefore not protected by any specific-IDP treaty. The only legal protection IDPs are afforded are those given by domestic or human rights laws. The remaining 22.5 million globally displaced are refugees recognized by the U.N. High Commission on Refugees as “someone who has been forced to flee his or her country because of persecution, war, or violence,” and who has a “well-founded fear” of persecution. Refugees are afforded greater legal protections under the 1951 Convention Related to Status of Refugees, such as the right to work, housing, education, public relief, freedom of religion, issuance of documents, and non refoulement — return only when safe to do so.

But while the population of individuals needing aid has increased, their geographic distribution has changed as well. Reflecting broader growing rates of urbanization, refugees and IDPs are relocating to urban areas: of known refugees today, roughly 60-70 percent are in urban environments, while 30-40 percent are in camps. Historically, as cities like Moscow, Beirut, Phnom Penh, and Haiti have shown, many displaced individuals end up in slums.

Several factors have driven this urban influx, including economic opportunity, the desire for self-sufficiency, and worsening conditions in many refugee camps. Cities are spaces for opportunity, allowing displaced individuals to integrate themselves into local economies and education systems. Daniela Raiman, a senior policy officer at UNHCR, told the HPR that this demographic change can also be driven by an individual desire or based on whether government encampment policies allow resettlement into urban areas. According to Raiman, the number of humanitarian NGOs and international actors has also increased.

Importantly, this refugee urbanization places a strain on local institutions, resources, and service delivery. Humanitarians eventually realized that the traditional model of aid delivery needed to be updated to reflect the new challenges of urban aid, including conflict in urban settings, displaced individuals relocating to urbans settings, and natural disasters in urban areas.

Standards for Aid

With increasing number of individuals in need, ensuring that appropriate levels of assistance are delivered can be daunting. In 1997, an organization of NGOs and the International Committee of the Red Cross created the Sphere Project, a handbook that sought to improve the delivery of disaster-response aid. The book is organized around four minimum standards — WASH (water supply, sanitation and hygiene promotion), nutrition, shelter, and health action. Sphere’s Aninia Nadig, who is responsible for the production of the handbook, told the HPR that, “the standards are universal to how they are formed” and are applicable in any situation. Within the minimum standards are indicators, or more flexible individual measurements, of whether the standard has been achieved.

Importantly, these standards are voluntary, with no compliance mechanism in place. Pamela Sitko, who previously worked for World Vision and is assisting Sphere in their revision for urban contexts, told the HPR that for Sphere, “It’s not the expectation that people should follow it, it’s the hope.” The Sphere Standards envision accountability to the populations served and not creating further harm. Sitko emphasized that “this is a standard that you willingly follow or not. Because nobody owns it and because everybody inputs into it, there’s a really great community sense of we all own this together.”

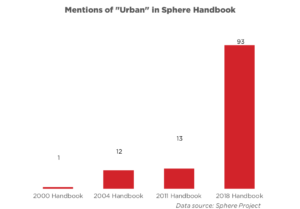

Likewise, these standards are not the only ones around. UNHCR, for example, has its own set of standards and indicators that predates Sphere, but Raiman explained that the two standards have seen more harmonization. Of such standards, Sphere is the most popular. In 2016, Sphere conducted a survey about the use of its handbook, and found that 80,000 humanitarian practitioners use the Sphere handbook, and of those surveyed, 75 percent had used the handbook within the last six months. Sphere has released three handbooks, one in 2000, 2004, and 2011. The fourth handbook is being released later this year.

In light of demographic changes, Sphere is tasked with updating its handbook to reflect new populations, NGOs, and issues of urban settings. UNHCR’s Raiman admitted that previous Sphere hand books have been “actually kind of biased” in their focus. From Raiman’s perspective, the handbook’s previous interventions and standards were catered to aid conducted in a camp environment, as opposed to urban settings. Dr. Ronak Patel from the Harvard Humanitarian Initiative agreed, calling Sphere’s institutional legacy “the old humanitarian approach of ‘let’s build a refugee camp in the middle of nowhere, and here’s a how-to manual’ … That was kind of that prototypical mindset of humanitarians in the ’90s.”

Patel argued that this mindset is no longer applicable, because “in a refugee camp that you’re building from scratch, you’re just doing everything yourself. ” In cities, however, humanitarians are “integrating into a preexisting urban planning process … a preexisting fabric that doesn’t meet anything like those Sphere Standards.” He determined that most of the Sphere standards were “not appropriate” for such urban settings.

Part of this incompatibility is due to the unique challenges that urban environments present. Patel told the HPR that an additional challenge is the slums, where even before a crisis individuals are living below Sphere minimum standards. In slums, which Patel dubs “the next humanitarian crisis,” it can take 10 minutes to find a bathroom serving 200 people with a usage fee. Indeed, many slums face poverty, new types of conflict, lack of access to basic services, and alarming levels of malnutrition — conditions that are the norm for its residents.

Posed with differences between desired standards of living for displaced individuals and the baseline level of the slums, humanitarians have difficulties coming up with an exit strategy, and must face the reality of having to do development work ad infinitum. This reality of simultaneous development and aid work in urban settings is driving a reckoning and revision of the Sphere Handbook.

Revising the Rules

According to UNHCR’s Raiman, Sphere’s revision is moving away from a camp-based narrative. In 2016, Sphere published a companion book on adapting its standards to urban settings to account for this gap. The forthcoming 2018 handbook will implement drastic changes in Sphere’s treatment of urban settings. For example, the word “urban” jumps from 13 appearances in the 2011 handbook to 93. Raiman asserted that Sphere has been intentional in this change, as “the camp-focused interventions are being consciously removed.”

Sphere’s Nadig attributed this increasing focus on urban settings to the earthquake in Haiti, calling it a “big trigger” for discussions on how to adapt Sphere. HHI’s Patel agreed that Haiti was a “big awakening” for many humanitarians. During Sphere’s revision, its writers had to examine the incompatibility of certain aspects of existing practices with urban environments — for which Haiti provided a case study. Nadig explained that around 2012, Sphere began discussing urban aid with HHI. Sphere quickly realized that camp-based practices such as “drilling water holes” were nonsensical in urban contexts.

Other NGOs followed Sphere’s urban shift. Sam Saliba, an Urban Technical Specialist at the International Rescue Committee, told the HPR that “There was a big recognition in 2015 … that we need[ed] to do some more thinking about this, to do intentional thinking about this.”

Sphere’s lengthy revision process reflects that intentionality: to execute this revision of the handbook, Nadig called upon experts to revise chapters of the handbook, which focus on core standards, and “thematic experts,” who specialize on topics such as urban aid delivery. Working together, these two teams “developed two drafts that were then sent out for consultations,” balancing input from a variety of NGOs and international organizations. The Sphere Revision’s Sitko explained to the HPR that individuals tasked with Sphere revisions review comments, look for evidence in every revision they make, and track their rationale.

As part of this process, Sphere consulted with experts to determine if urban-specific standards were needed. The debate centered around the confusion between standards and indicators — Nadig argued that “the problem Sphere often has is there’s a standard and there’s an indicator with a number in it, and people think ‘that’s what we need to do,’ and it’s not that straightforward.” From this assumption stems confusion, where individuals “mix up the standard level — which is the qualitative, high level expression of a right to something — and the indicators,” which are more specific guidelines. Saliba concurred, telling the HPR that in his opinion, a large challenge for humanitarians is an “over-reliance on standards of practice.”

Sphere ultimately decided against urban-specific standards, choosing instead to maintain their set of “universal” standards, but to advocate for contextualizing their indicators to urban contexts. In essence, the Sphere handbook is maintaining its core standards of WASH, nutrition, shelter, and health action, but is updating its measures of these standards for urban settings. These indicators will be flexible to each environment humanitarians work in, allowing them to customize their approaches while staying under the broad umbrella of core standards.

Location, Location, Location: the Localization Agenda

While standards look good on paper, following them in urban environments is a new puzzle. Though the standards aim to be universal, every urban environment is unique: as Sitko told the HPR, “I did some research in Bangkok, and one neighborhood that was 800 meters away from another neighborhood was so different in its social composition than the one next to it.” In order to customize their care, humanitarians must consult experts — local actors. Sitko elaborated that “creating standards that apply to all cities around the globe is extremely complicated. So, I think one of the best things we can say is ‘context analysis’ is really important, and so is nuance.” HHI’s Patel concurred, maintaining that coming up “with a new way that is appropriate for different cities and different contexts and climates and different cultures” is nigh impossible. He also stressed that contextualization is where humanitarian standards must head, especially in light of broad universal standards. What Sitko, Patel, and NGOs worldwide have discovered is that to avoid mishaps in aid, as in Haiti, humanitarians have to understand the urban environments they work in.

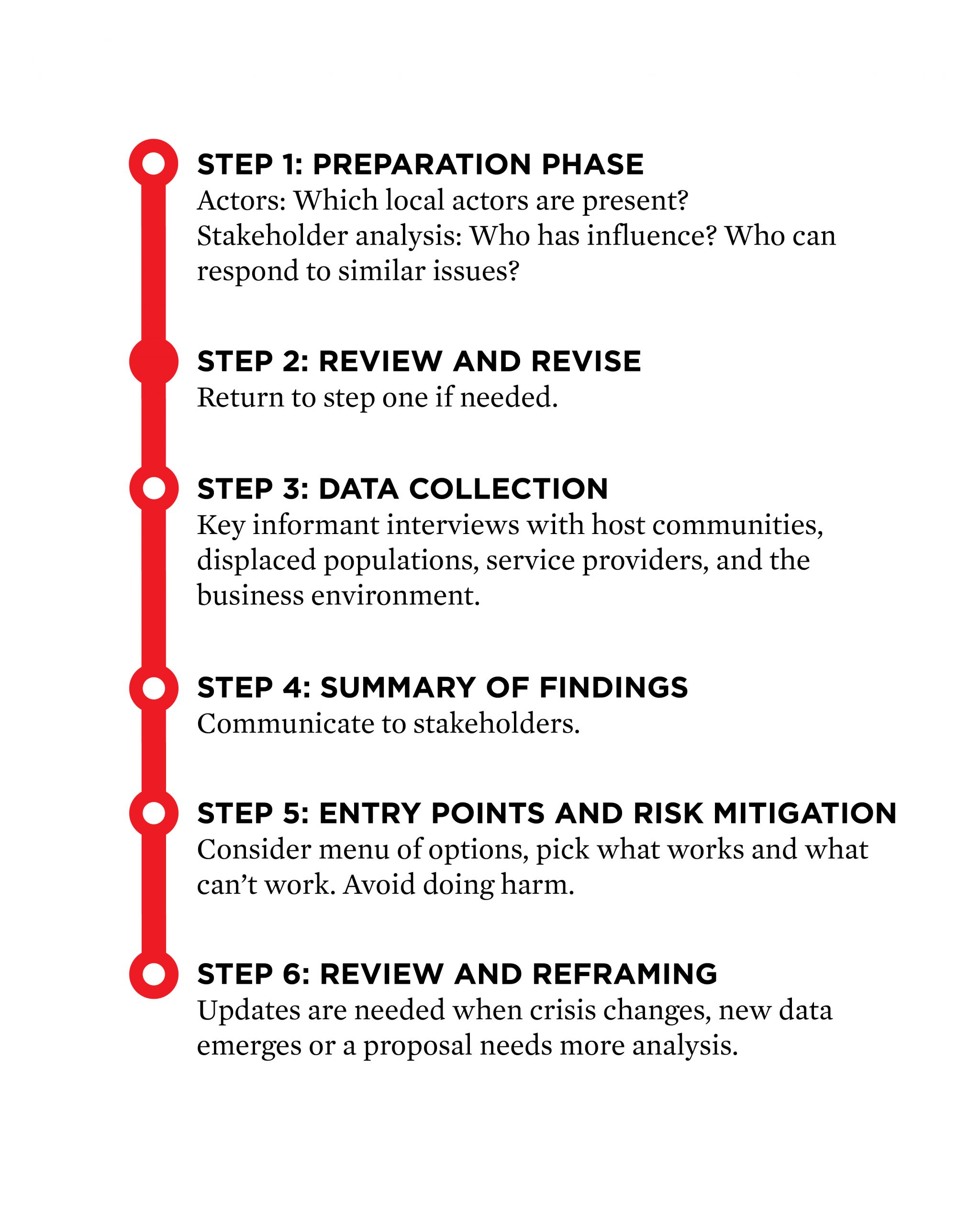

To determine how to customize aid to each urban environment, most humanitarians rely on context analysis — in-depth study of the actors and social, economic, and political conditions that impact crisis response. Context analysis allows aid workers on the ground to understand the situation at hand, assess the authorities and service providers that they would have to work with, and identify entry-points for response. IRC’s Saliba told the HPR that context-analysis allows aid workers to approach a disaster “like a decision-tree, where you pick up certain recommendations or standards that we’ve given, but drop others.” According to Sitko, this context analysis has to be regularly updated, because situations change quickly, possibly nullifying a previous response program.

Contextualizing aid comes down to inclusion, done through assessing the new stakeholders, who will work with NGOs to implement programs. Sitko explained that “when we talk about coordinating, we have a whole new set of stakeholders we have to coordinate with at the local level and higher … speaking locally, you might have to coordinate with the mafia, or the gangs. You might have to coordinate — definitely — with the private sector. You’re coordinating with local politicians, who are providing food and assistance and that sort of thing.”

Sitko elaborated that local stakeholders were central to humanitarian aid because “those people are the first responders. They know better than anybody else what the power dynamics are, maybe where some of the entry points for change can be, and they also know where the tensions are, where the connectors/where the dividers can be found.” Indeed, Haiti’s failure can be partially attributed to the fact that local NGOs, who truly knew where needs were most pressing and where redundancies could be avoided, were left out of consultations. Without the guidance of local actors, Humanitarians run the risk of operating a formulaic aid-delivery model that cannot adapt to local circumstances.

But not all aid workers come in with the same agendas and mindsets, and tensions can emerge between local and international actors. This challenges of localization stem from the fact that, according to Patel, humanitarian actors are “coming in as this largely Western, international humanitarian system and coming in with our ideas of what is right and wrong” based on previous crisis responses. However, these perspectives are often not compatible with the local context, meaning humanitarian actors must have the “humility” to adapt practices to local stakeholders. For World Vision’s Frederick, this presents issues when governments have particular policies of their own that are not compatible with humanitarians’ “contextual variations.” Frederick told the HPR that he navigates these issues through negotiation, which brings occasional success or resistance.

Aid actors today seem to be taking these challenges of localization head-on. Funding sources of NGOs — like USAID and the State Department — have begun to require that donors add aspects of contextualization to reports and interventions. Raiman asserted that UNHCR is active in the localization agenda, as it collaborates with “the appropriate services and ministries” responsible for the paperwork that determines refugee status. Other NGOs, such as the IRC, have focused on working with local governments in cities where displaced individuals have resettled, among them the Greater Amman Municipality and Kampala Capital City Authority. Through those partnerships, the IRC has, according to Saliba, shaped a strategy around “the inclusion of refugee and consideration around refugees in existing urban processes.” Frederick told the HPR that in Iraq, World Vision coordinates with the local health department on issues related to WASH. In Mosul, Jenny Lamb told the HPR that Oxfam works with the Iraqi Health Ministry as well, specifically looking at disease data and epidemiology, collaborating on how actors can “scrutinize and then respond quickly.” These examples of contextualization, and partnerships with local actors, demonstrate the efficacy of those humanitarian aid agencies that learn to adapt to new circumstances.

The Development Divide

While local mapping with stakeholders has to occur, international actors also have to coordinate amongst themselves to ensure that their missions, priorities, and organizational structures align. Many international NGOs have established working partnerships with agencies like UNHCR, but urban humanitarian aid exacerbates the need for coordination occurring under these models.

As the IRC’s Saliba said, “everybody’s tangentially related to urban.” This creates challenges in coordinating diverse parties — such as humanitarian and development actors, donors, and UN agencies — whose mandates may briefly touch upon urban settings. Sitko connected this amplified coordination challenge to power. As she told the HPR, “what’s really interesting for aid agencies in cities [is] that we have so much less power than we do in rural areas.” She further added that the number of stakeholders in cities are higher, requiring negotiations over a small area of influence.

Looking deeper into power tensions, one discovers that it is most jarring when it comes to interacting with development actors. Traditionally, humanitarian aid and development were seen as two different entities, with two different mandates. Development mandates, like that of the United Nations Development Program, strive to design policies for human development, specifically addressing poverty. Humanitarian aid timelines are more immediate, focusing on pressing needs. UNHCR’s Raiman explained that these differences even come down to funding models, telling the HPR that “on the humanitarian side you’re usually [functioning on] a short term budget.” In delivery of aid, the humanitarian side has historically created “parallel services,” where education, shelter, food, and clinics are provided to refugees from the international community. This model was well suited to camps. On the development side, an “integrated services” approach has been taken, where a host country provides services to refugees with financial and implementation support from outside actors. Integrated services — given the cooperation needed with local actors — are more compatible with the rise of the localization agenda.

The rise of urban refugees, along with a lengthened operational timeline due to protracted crises, have challenged humanitarian aid’s parallel services model. In urban areas, where municipal authorities already exist, providing purely parallel services is costly, perpetuates segregation, and prevents self-reliance. Parallel services can also weaken local service deliveries, as was seen in Haiti.

As crises became longer, humanitarian agencies began to realize that displacement is becoming a semi-permanent condition. However, due to the structural differences in humanitarian and development, the two actors still operate separately in the field. Saliba calls this phenomenon “parallel tracks,” where development actors and humanitarian actors work “without really coordinating, specifically when it comes to public service delivery.” Frederick reiterated this issue, stating that coordination and avoiding duplication is difficult. In essence, the mandates and focuses of humanitarian and development actors have begun to converge in the field, but the institutional structures remain separated. Faced with the possibility of providing parallel services for extended periods of time, humanitarian aid actors and Sphere have begun to realize that coordinating with development agencies is increasingly a necessity.

Bridging the Gap

Beyond large-scale institutional changes, NGOs have also taken to breaching this gap individually by focusing on recovery and resilience. In this context, recovery involves capacity building, a more immediate process of working with local governments to deliver services. IRC’s Saliba explained that the need for capacity building emerges from “thinking about how we are strengthening the existing systems for the long term, especially once humanitarians leave.” More preemptively, resilience looks forward to protect urban areas from future vulnerabilities, such as natural disasters, while also improving the quality of life of displaced populations through poverty alleviation and urban development. HHI’s VanRooyen told the HPR that capacity building is easier to do in natural-disaster plagued cities than in conflict-plagued cities, due to conflict interrupting ties with local governments.

Lamb explained how Oxfam has increased its focus on recovery and resilience bringing in more specialists to address this issue, such as anthropologists, financial and market specialists, the CDC, and the private sector. Cooperative for Assistance and Relief Everywhere (CARE) updated its urban aid delivery by partnering with development actors such as loan associations. Action in the field, however, needs to be combined with institutional changes in NGOs — Patel argued that if humanitarians “don’t have urban specialists or urban planners there, they need to get them.”

One unintended consequence is the cost of coordinating all of these new actors. Although coordination costs themselves compose less than one percent of humanitarian aid from the Cluster model, Patel relayed that “doing really great coordination with the local actors … and coming up with very great, locally contextualized tools and metrics and scales and assessment surveys, both of those take a lot of effort and a lot of time.” A 2016 Rand Report reported that the UNHCR’s administrative costs composed 66 percent of its budget.

Reflecting on these changes, Saliba sees urban coordination on a local and international scale as a positive trend, telling the HPR that “there’s a big difference between when I started [in 2015] and today. There’s not a big difference between last month and today. So it’s been a very slow progress, but it’s been progress.”

Ending the NGO Republic

Although a focus on urban areas, intentionality, and increased coordination promise an improved capability in humanitarian response, one huge obstacle remains in the way: access. Specifically, being able to reach affected populations may encumber aid efforts and assessments of how effective increased coordination is. Raiman told the HPR that the UNHCR might not actually be reaching the 70 percent of displaced individuals in cities. To Raiman, this is vastly different than camps, where humanitarians are fully responsible and able to physically locate their served populations.

World Vision’s Frederick is stationed Erbil, Iraq, which hosts refugees from the Syrian refugee crisis and Iraqi IDPs. He noted that “there’s a vacuum of knowing where [beneficiaries] are, what has happened to them, whether they migrated to Europe or they have gone back to place of origin, or they’ve chosen to be invisible or anonymous.” His affected populations show up during service delivery, but he is unable to track them afterwards. Oxfam’s Lamb reaffirmed this problem is unique to urban environments, stating that in camps, “it’s pretty easy to go out and speak with communities under a tree,” but that finding aid beneficiaries in cities requires more creativity. She recounted that aid agencies have to find refugees and IDPs in “schools, mosques, women’s groups, or through marketplaces.” Sometimes, even WhatsApp or radios are used to find those in need of aid.

Urban aid is stretching the boundaries of what was known in the humanitarian community. The new methods of coordination, need for integrated services, and difficulty of even finding affected populations have all required humanitarian organizations undergo rapid transformations, and organizations like the Sphere Project are trying to keep up. With protracted crises yielding new insights and best practices every day, the web of knowledge regarding urban aid is widening. What is left to determine is if this coordination will one day be proactive and collaborative with affected governments. If so, Haiti may be both the first and last NGO Republic.

The cover art for this article was created by Mai Saito, a student at the Pratt Institute, for the exclusive use of the HPR’s Red Line.