Since undergraduate housing assignments were first randomized in 1995, Housing Day at Harvard has grown to be a rite of passage for freshmen, as they anxiously await the hoards of rowdy upperclassmen “dorm storming” the freshman dorms and informing students of their housing assignments. However, for a handful of freshmen, housing day is bittersweet. Many freshmen that are unsatisfied with their housing assignment tend to be those who were “quadded” — sorted into one of the three upperclassmen houses in the the Radcliffe Quadrangle, 0.7 miles away from Harvard Square. Athletes are particularly inconvenienced by this distance, as many have to wake up earlier than their peers to make it to early morning practices — many of which take place across the river in Allston, a little under two miles from the Quad. While the Office of Student Life states that the housing lottery is random, some students, as well as a separate project by the Harvard Open Data Project, suggest otherwise.

Using data from the past four years made available by the Harvard Athletics website, we seek to address the question of whether or not athletes are evenly distributed between the houses. There are two factors that affect athlete distribution through the houses: initial placement and transfers. Using this data, we look at house distributions and track athletes as they move between the houses. Students are in upperclassman housing for three years, so this four-year data set allows us to see two distinct sets of students, reducing the effect of year-to-year variances in housing distribution in our overall analysis.

We find that while athletes do transfer from the Quad to ‘river houses’ at a much higher rate than in the reverse direction, the initial distribution of athletes their sophomore year shows no favoritism to any one house. Blocking groups — groups of up to eight students choosing to be sorted into the same house — can make athlete distributions appear uneven year to year, but over this four-year period there are no consistent trends in where athletes live.

Where Do Athletes Live?

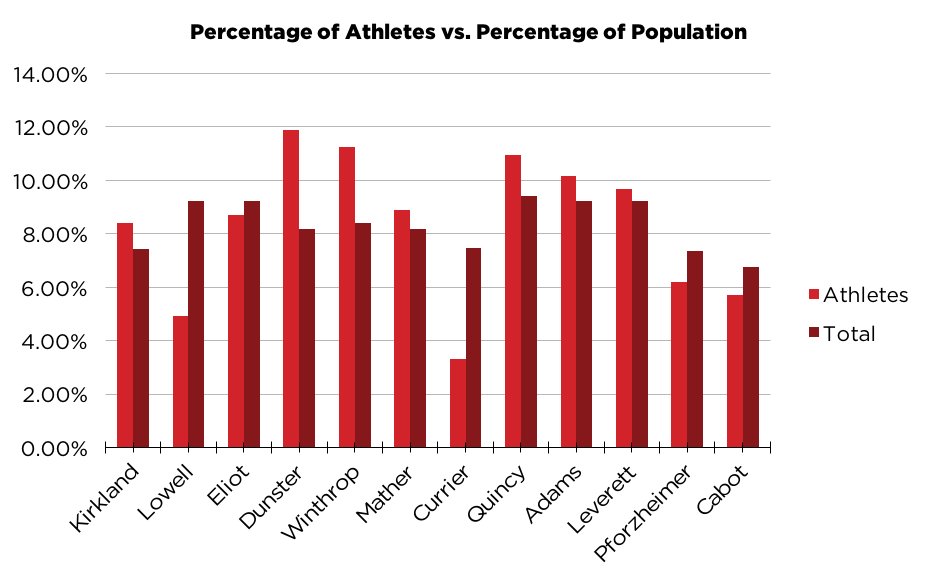

We use housing data on athletes from the 2017-2018 academic school year to evaluate the percentage of athletes living in each of the four groupings of upperclassmen houses: The Quad (Cabot, Currier, Pforzheimer), River West (Eliot, Kirkland, Winthrop), River East (Dunster, Leverett, Mather), and River Central (Adams, Lowell, Quincy). Across the four groupings, the Quad has the lowest percentage of athletes at 15.21 percent. Each of the other three groupings of river houses outweighed the the Quad by over 10 percentage points — the percentage of athletes in River Central at 25.99 percent, River West at 28.37 percent, and River East with the highest percentage at 30.43 percent.

The table above compares the percentage of athletes versus the percentage of the total population across all 12 houses. The highest percentages of athletes are in Dunster, Winthrop, and Quincy, with other river houses falling closely behind. This data reflects the higher percentage of athletes in river houses in general, and not necessarily the popularity of a specific river house.

It is worth noting that only 59.5 percent of athletes competing in the 2017-2018 academic year have a house listed on the Harvard Athletics website. Excluding the 26 percent of athletes living in Harvard’s freshman housing, this means that 14.5 percent of athletes are not accounted for in this data. We don’t believe that this gap in our data set drastically skews the data toward any house, as athlete biographical information is posted by the Athletics Department and therefore not an effect of house affiliation.

However, missing athlete biographical information does correlate to teams. Track and Field had 25 non-freshman athletes on their roster with no biographical information. This was a significantly greater number of athletes than Baseball, which had the second greatest number of omissions at 9 players. 51 percent of teams have fewer than four non-freshman athletes without a listed house affiliation. This could have implications on our data as athletes on the same team tend to block together, so it is possible that there exist groups of athletes from these teams with lower house reporting rates that all live in the same house, which could mean our data is skewed.

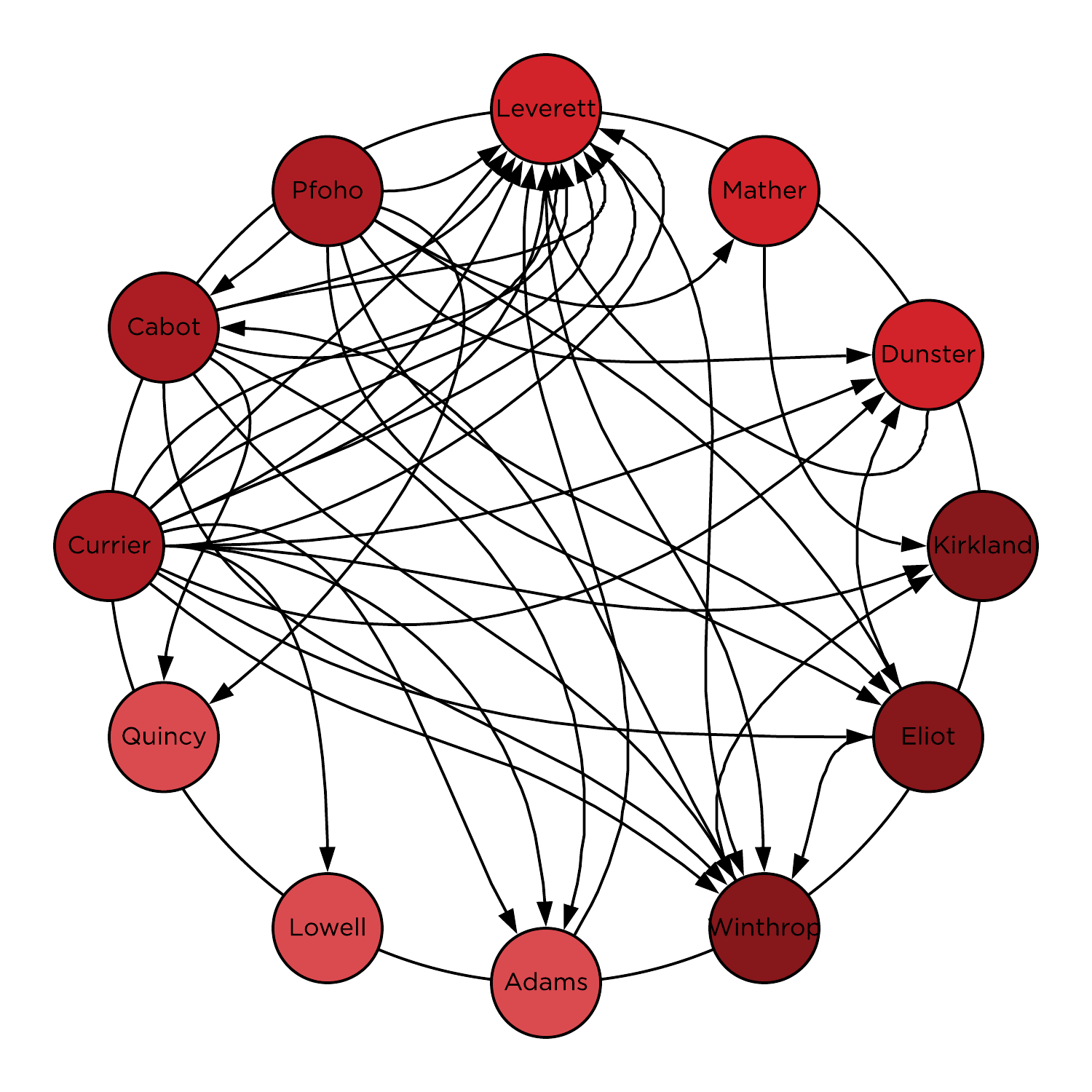

The above flow diagram displays transfers between houses. In the 2014-2015 academic year, there were a total of 17 transfers recorded among athletes. In 2015-2016, this number substantially decreased to nine. In 2016-2017, the number fell even further to six. While there were transfers between river houses, most transfers were from the Quad to a river house and we found no record of transfers from river houses to the Quad by athletes.

The high number of transfers in 2014-2015 was also matched by a mass exodus of athletes from the Quad. A large proportion of the 17 transfers were due to athletes leaving the Quad for various river houses. This high number of transfers out of the Quad is visualized above.

Historical Breakdown

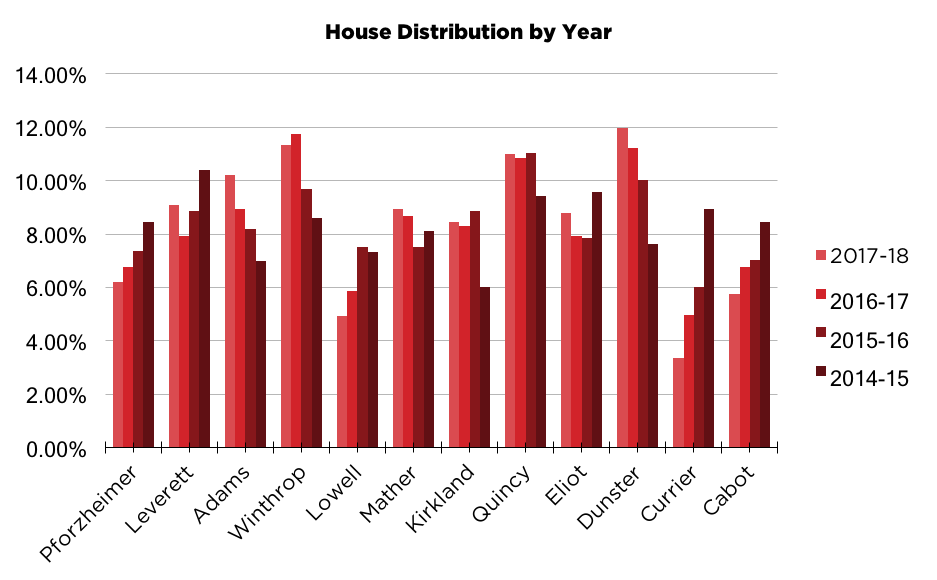

The breakdown of athlete houses over the past four years gives a significantly different picture than just the 2017-2018 breakdown. Currier, for example, housed the least athletes — just 3.35 percent — in 2017-2018, but it made up the fourth largest percentage of athlete housing in 2014-2015, when 8.94 percent of athletes lived in the house. In 2014-2015, 25.85 percent of athletes lived in the Quad, compared to just 15.21 percent in the 2017-2018 academic year. Looking at the above data, a significant portion of this decrease can be attributed to the exodus of Quad athletes in 2014. However, in the three years since the percentage of athletes living in the Quad has decreased at a steady rate.

All three Quad houses have seen a decrease in the percentage of athletes that they have housed over the past four years. Lowell has also seen a nearly continuous decline. Dunster, Winthrop, and Adams have seen continuous growth in their percentages of athletes. However, for the most part, the percentage of athletes living in a house fluctuates randomly by year. Some choppiness between these fluctuations has to do with the size of blocking groups.

Blocking Groups

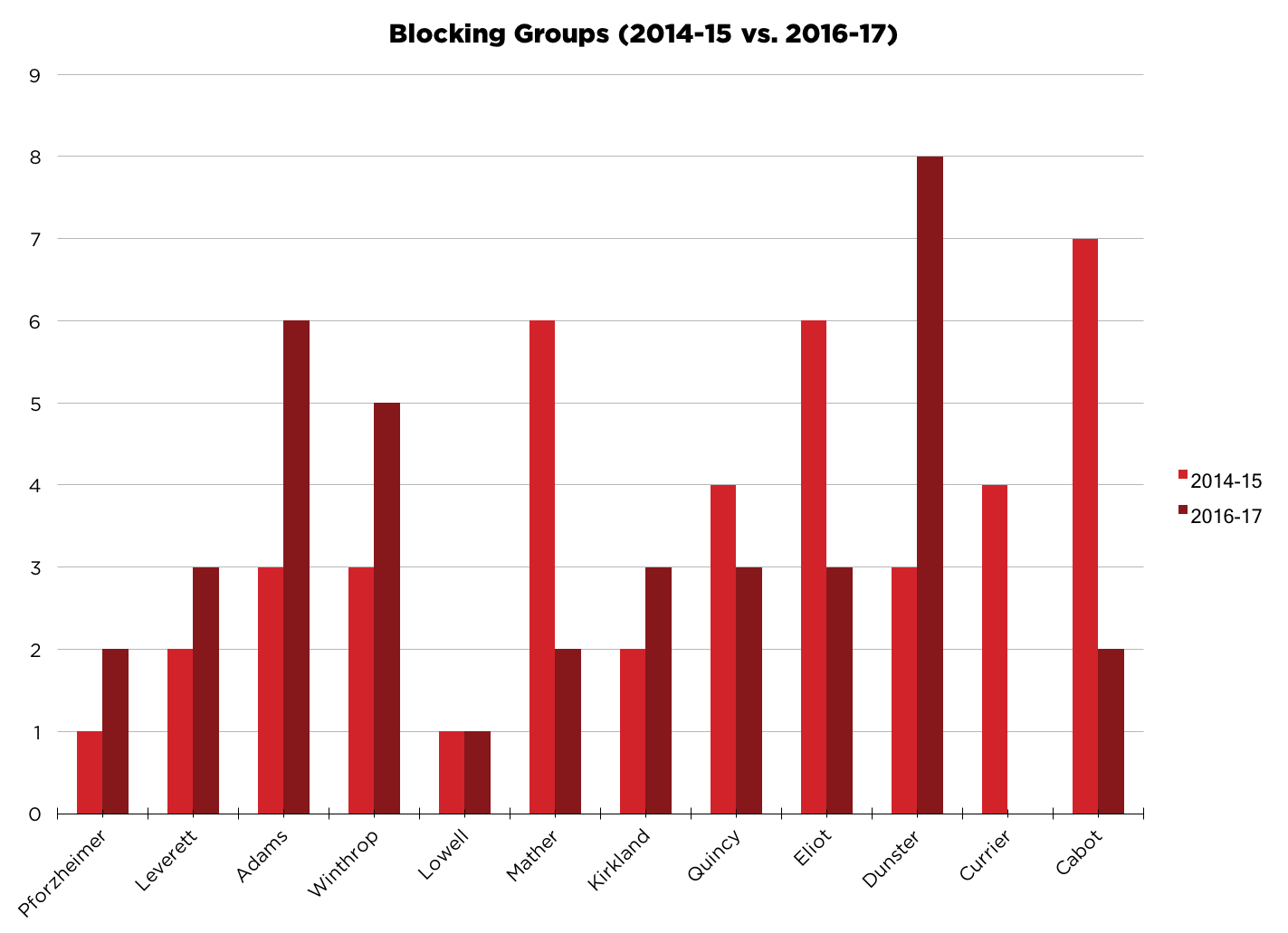

Harvard allows freshmen to form “blocking groups” of up to eight students that are guaranteed to be placed in the same house. The distribution of athletes among houses can be substantially influenced by the composition of blocking groups. If a number of athletes block together, their house may experience a significant increase in its athlete composition.

We define blocking groups as groups of four or more athletes on the same team, in the same year and the same house. This definition relies on the assumption that teammates in the same house were more likely to have blocked together rather than have been members of separate blocking groups placed into the same house. Not all athletes were accounted for in these counts of blocking groups. This is either because they were in blocking groups of less than four individuals, blocked with athletes from other teams, or did not block with their teammates. We identified 38 blocking groups during the 2017-2018 academic year. Furthermore, 12 of these blocking groups had at least six athletes in them. These blocking groups are significant as they skew the data and make it slightly choppier. Since each house has on average 53 athletes, if one house gets one or two more blocking groups than another, it will significantly skew their percentage of all athletes. As the below diagram shows, the distribution of blocking groups varies significantly year to year.

Conclusions

It appears that athletes are randomly distributed among their houses during the initial placement at the end of freshman year. Sophomores in the 2017-2018 academic year were slightly more evenly distributed than juniors and seniors. However, this distribution is still somewhat uneven. This can be attributed to the fact that athletes tend to block together, and even a slightly disproportionate distribution of blocking groups can result in a more significantly uneven distribution of athletes over the houses.

However, even when athletes are evenly distributed, an increase in transfers in the year following an even distribution brings this distribution back out of balance. This was observed following the 2014-2015 academic year when 17 students transferred, the majority out of the Quad.

Overall, while a number of athletes transfer from the Quad to river houses each year, the distribution of athletes among the 12 houses from our data appears random. However, we believe longer-term data would help to conclude that there is no bias regarding which houses athletes are placed in. We took a sample over four years, looking at two distinct sets of students. However, we saw that certain variations from year to year, such as the exodus of students from the quad or a number of athlete blocking groups being placed in one house, can skew the results for the three years that the athletes are in that house.

This article is the product of analysis by the Harvard Open Data Project, a student-faculty group that analyzes public Harvard data to hold Harvard institutions accountable. The raw data can be found here.

Ariana Soto, Madeleine Nakada, and Stephen Moon contributed to this article.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Nick Allen