Most issues in U.S. politics exist at the extremes. Should the government expand public health care or expel it? Should the United States open its borders or slam them shut? Should Congress advance gun control measures or retract them? In each instance, significant ground stands between the opposing sides. This trend is observed both within the current legislature and from the populace. As Harvard professor Ryan D. Enos told the HPR, “One thing that is fairly well understood in the study of political science is that mass politics tends to follow elite politics. It seems that when people face complex political decisions (i.e. what policy should they favor, what does it mean to be Republican or Democrat), they follow these elites.” All of this raises an interesting point—how did the United States’s current polarized position arise?

As Psychologists David Myers and Helmut Lamm argue in their groundbreaking, group-decision making study and as Professor Daniel Isenberg of Babson College furthers in his own group-oriented research, inserting random individuals into a random room to discuss a random topic provides some extraordinary results about human social and political interactions. By most accounts, the group will choose a more extreme answer to the argument than any of the given individuals. More specifically, as Professor Myers claims, “Groups are, on the whole, more risk-prone than the average individual member.” Such results seem to arise from two interconnected actions by the group members. When these random individuals meet, they all consciously scrutinize each other, searching for some facet that places the individual above the rest. As Professor Isenberg states, “An individual must be continually processing about how other people present themselves, and adjusting his or her own self-presentation accordingly.” Everyone in the group wants to fit in by copying one another.

At the same time, an opposing process occurs during which each person desires individuality—a separation from the group. In a social sense, this theory explains how groups force each member into a more radical direction to ensure both that the group is heard and that each member is unique. Moreover, in a political sense, this theory helps to explain how the Republican and Democratic Parties have become increasingly separated, constantly pushing away from bipartisan compromise and towards specific attention. This desire for individuality does not exist in an “every politician for himself” mentality, but rather an “every sect for itself” one. The best example of this phenomenon was the Tea Party Movement in 2010, which forced conservative, grass-roots individuals further away from their party’s center and closer to its extreme. This crusade arose because others, like the Obama Administration and GOP elites, were not listening. Thus, these conservatives were propelled into their own, individual faction.

Though, as Professor Enos warns, “Maybe this is psychological, but part of it is also coming from a mass reaction to elite polarization.” With many elites trying to fit into the political game while simultaneously grasping to preserve some individuality, the United States population has at times followed in suit, shifting either more left or more right to fit into the elites’ parameters for what constitutes a Republican or Democrat. For example, research by Assistant Professor in Political Behavior Thomas J. Leeper of the London School of Economics shows that polarization occurs because of the original strength of one’s convictions rather than the quantity of exposure to such ideas. This means that politicians—individuals who make a living by wielding strong convictions about an array of topics—are much more likely to combat opposing ideas and individualize than the masses, especially if such a move provides more power or a stronger message. With these politicians then looking out both party and self, one of the ultimate results is an endless stream of unconsciousness, of inactivity, of myopia, and of ignorance. Or, in more concrete terms, the U.S. Capitol has become the host of an unending parade of fiscal disputes, gun control deliberations, healthcare evaluations and reevaluations and re-reevaluations, and sufficiently little change (in either direction) in these categories. Evidently, U.S. politics has grievously metamorphosed over the past several decades largely because of group polarization from domestic issues. With this new status quo of discordance, the United States is now its own worst enemy, destroying itself from the inside with political extremism. As Wordsworth penned over 150 years ago, indeed “The World Is Too Much With Us,” for the current climate of political polarization has effectively generated a new, deeper divide both between and within parties that has weakened their ability to function, removed their authority to speak for the citizenry, and effectively created a newfound form of “appearance over action” politics. Today, politics are vicious and ugly and gridlocked; the only question left to ask—how do we fix it?

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!…

Everyone’s a Critic

Let’s begin with a simple question: for whom will U.S. citizens vote in the next election? The options: Clinton, Sanders, Trump. The results: thoroughly split. According to current primary results and to an April 14th poll from NBC news, approximately half of Democrats support Hillary Clinton, while another 48 percent back Senator Sanders. On the other side, a CBS poll on April 12th found that 42 percent of Republicans wanted Trump in the White House, 29 percent preferred Cruz, and 18 percent preferred Kasich. None of these statistics are particularly shocking or enlightening—Clinton and Trump have remained the front runners since their announcements to run. Rather, the most intriguing polls report the likelihood that voters, assuming that their candidate lost, would or would not vote for their party’s nominee.

Thirty-three percent of those favoring Bernie Sanders will probably not vote for Clinton in the general election, according to a Wall Street Journal poll from early March. Following in suit, a Pew Research study from March 31st found that only “38 percent of GOP voters believe the party would ‘solidly unite’ behind Trump,” if he were to win the nomination over Kasich and Cruz, which, essentially, he has now done. Furthermore, an ABC News survey from mid-March found that if Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump were to win their primary elections, approximately 40 percent of voters would “seriously consider” third-party candidates. Moreover, only two candidates, according to an ongoing Huffington Post poll, possess a higher favorable rating than an unfavorable one—Bernie Sanders and John Kasich at 50 percent and 40 percent, respectively. Such a phenomenon may seem common with modernity’s cynical view of politics. However, Trump and Clinton have actually gained two records for disapproval. A CNN investigation in late March observed that since 1984, when their favorability poll began, no candidate has topped Clinton’s -21 rating (percent favorability – percent unfavorability) or Trump’s -33. In all, it appears that the nation’s political system incites more disgust than pleasure among its own citizens. In a country where everyone supports his Congressman, but no one supports the Congress (as Gallup data has suggested), should we have expected any better?

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;…

No More Middle Ground

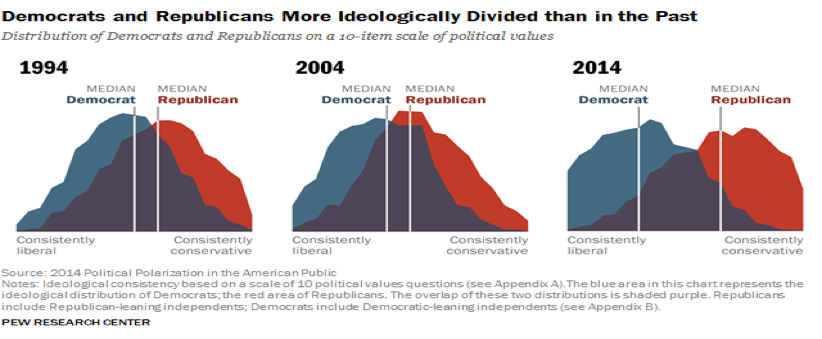

Over the last two decades, the Pew Research Center has recorded one of the most concerning trends in U.S. politics—rapid interparty polarization. As the chart below depicts, the overlap between the two parties’ similarities has dissipated sharply.

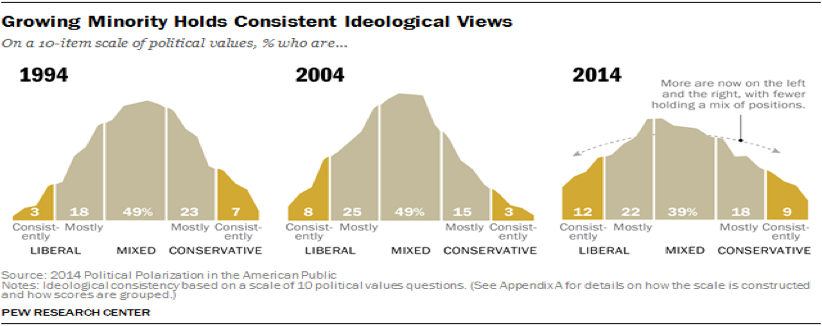

The most frightening piece of this image is not even the growing chasm between Democrats and Republicans, but rather the growing steepness of the two curve’s extremes. In 1994 the left- and right-most portions sloped downward quickly (meaning each step from the center to the ends caused a large drop in support). By 2014, this slope was observably smaller, meaning that fewer and fewer individuals withdraw their support from the extremes. As Professor Enos told the HPR, “It seems that a larger portion of the population is stacking up on the liberal and conservative sides of this dimension…perhaps because of increased sorting into parties.” This all shows that moderates are a dying breed—a political relic, literally fighting an uphill battle in this image. Coinciding perfectly with this perception, Pew Research also submitted an image of national moderateness over the past twenty years. The results: again, not pretty.

Whereas moderates remained a strong majority within the United States between 1994 and 2004, recent history has seen the left wing of the left wing grow by four times since 1994, while the right of the right grew three times as large since 2004. Even considering expected fluctuations of party strength from year to year, the clear downward trend in moderateness only reinforces the incongruity of the current election cycle. With more and more citizens staunchly attached to their irreconcilable political views at both extremes, it seems only natural that the two frontrunners possess more disapproval than approval, regardless of their stances on any issue.

This sets up a highly paradoxical view of politics when incorporating the statistics about voters not supporting their party’s nominee if their first choice loses. Whereas some may view more polarization as a strengthening of party lines, much data disregard this notion. On the contrary, it appears that such diverging shifts actually weaken the two party structure by heavily splitting votes. As stated earlier, 33 percent of Sanders supporters say that they will not support Clinton in the general election. Because Sanders is known for his political extremism—what he calls a “political revolution”—it appears that many of his support-base refuses to converge with the moderate alternative. All of this acknowledges that many polarized voters either can no longer ideologically relate to the center of their own party or refuse to compromise some of their fundamentalist beliefs. Regardless of the multiple rationales that comprise this 33 percent, the Democratic Party (like its Republican opposition) is clearly divided along unshakeable ideological lines in this election, exposing the incompatibility of politicians with the American people, as well as of the politicians with each other.

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;…

A Fish Rots From the Head

With extremism over moderateness, vanity over action, hubris over decency, and self-interest over cooperation, the U.S. political system has putrefied through and through, with political leaders diverging on most issues and dragging many constituents along for the ride. All of this converts a divided Congress into a divided nation into divided parties, which in turn, has produced the split, far-left and far-right candidates in today’s divided election. For many, this slippery slope has taken this country to a new low, a new era of gratuitous mudslinging and self-serving survival. Every day, citizens look to elected officials only to see them refuse Supreme Court nominations before any vetting, only to watch them shut down bill after bill in the name of special interests, only to hear them pass 143 pieces of legislation into law (the lowest amount in the past four decades), and only to feel them convert this division into their inaction. Whether it be from oil or education or medicine or communication, the government has increasingly transmuted into a slanted, disjointed system, where not every vote matters and where only those who force us further apart have a voice. Political elites are spurring an enormous divide within the United States, and dragging the masses with them. The fish rots from the head—is there still time to chop it off and save the body?

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

–William Wordsworth, 1807

Image Source: pixabay/BruceEmmerling