For nearly four decades, the United States has been losing a grueling ground war on several fronts. In 2016, casualties reached an all-time high and the federal government officially declared this conflict a “national emergency.” Even with over one trillion dollars spent thus far on the war effort, victory is nowhere in sight; deaths continue to spike and morale continues to be depleted. Americans are quickly losing faith in our leadership’s ability to devise any viable solutions to stem the death toll. Yet unlike America’s various military entanglements, this battle is not confined to the deserts or jungles of a far-off foreign land, but rages on in the medicine cabinets of every American household and in the neighborhoods of every town and city. Its effects are immediate, tangible, and real. This is the egregious state of modern drug addiction in America.

The Pain Epidemic and Opioid Epidemic are two theaters of operation in this public health emergency. According to the National Institute of Health, “Nearly 50 million American adults have significant chronic pain or severe pain.” Physicians have routinely treated chronic pain patients with opioids, believing them to be an effective means of palliative care when administered as directed by a physician. In 2015, about 92 million patients relied on opioid treatment to mitigate symptoms of pain in order to live a normal life.

Beginning in the 1990s, pharmaceutical companies including Purdue Pharmaceuticals began aggressively advertising their opioid products as an effective and less-addictive way to treat pain. With the introduction of Purdue’s most recognizable product in 1996, the extended-release opioid OxyContin, more physicians began to prescribe this particular medication as opioids were adopted as mainstream treatment for pain. Unsurprisingly, with an increase in opioid prescriptions, American physicians began to see an increase in the number opioid deaths.

This increase led many, including the Center for Disease Control, to believe that the abundance of prescription pills was responsible for rising deaths. However, a more rigorous look at the data greatly calls this relationship into question.

The Data

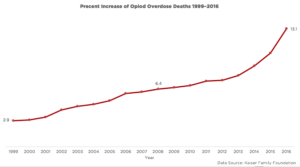

Between 1999 and 2015, opioid overdose deaths increased by 311%, while total opioids consumed increased by 215%. The correlation between prescribing and deaths over this total period superficially indicates a relationship between these variables.

Though increasing steadily from 1999, opioid prescribing actually decreased modestly after 2011. If one is to believe the narrative that opioid prescribing is causative of deaths, than one would expect overdoses to also fall in this period. This is not the case between 2012 and 2016, a period in which opioid overdoses have skyrocketed by 82%.

There appears to be more to the story than the popular narrative that overprescribing alone has created an “opioid crisis.” Even as prescribing has decreased over the last five years, deaths have continued to rise- at an even higher rate. Yet, mainstream public policy continues to be focused on limiting prescribing, though evidence suggests that this has actually caused the rate of overdose to increase markedly.

Solutions Lead to More Problems

In its fervor to combat the perceived “opioid epidemic” by limiting access to prescriptions, the federal government has actually made matters worse. Policy at both the state and federal level has attempted to limit a physician’s ability to treat pain patients with opioids. Throughout the last decade, the Drug Enforcement Administration has conducted a series of raids on “pill mills” across the country and clinics marked by the high volume of prescribing.

Fear of being prosecuted for accidental overprescribing puts doctors in a difficult position creating an incentive for providers to limit treating patients with opioids, despite their medical efficacy. In turn, these restrictions have had a detrimental effect on overdoses. As one study from Huecker and Schoff notes, pill mill raids are responsible for an “increase in distribution, abuse, and overdose of heroin.” Several states have also seen pain patients resort to heroin use when prescription opioid availability is limited.

If a patient is using prescriptions opioids to treat pain, and is then cut off because of restrictions, that patient has no other choice but to seek out illicit drugs on the black market. Dr. Mark Albanese, a Somerville-based doctor who treats addiction, noted to the HPR , “It’s absolutely clear that as the faucet got turned off on the opioid pain medication, people did turn to…heroin and other synthetics, but I suppose fentanyl particularly.”

This poses a serious danger. Inherent to underground markets is a lack of information about the true contents of the products. Because information about illegal substances cannot be openly advertised or labeled, “accidental poisonings and overdoses will occur more frequently in a prohibited market.” Federal restrictions on access to legal opioid prescriptions are misguided because policymakers do not take into account these negative consequences.

Overdose Deaths by the Numbers

This hypothesis—that the substitution for street drugs is responsible for the recent spike in opioid deaths is supported by the data. According to a recent study, overdose deaths more than doubled in 2016 due to illicitly manufactured fentanyl from less than 10,000 to 20,000. Overdose deaths are not presently increasing because of overprescribing. On the contrary, it is the sudden stop in prescribing that seems to be responsible for patients being forced out of the care and supervision of a physician and into the uncertainty of the black market. As one user told the Dallas Observer, “I finally broke down and did something I swore I would never do… I purchased my first gram of heroin to alleviate the pain and withdrawal. A Google search and a trip to the local gas station later (to buy a lighter), I was now part of the problem…” This person using drugs is not unique in his or her experience, but representative of a class of individuals struggling with pain who are forced into harm’s way by heavy-handed, misguided policy. Furthermore, this instance demonstrates just how easy it is to obtain street drugs. Therefore, as long as a patient who is cut off from a physician’s treatment can easily access potentially dangerous drugs from the street, limitations on opioid prescriptions will likely accelerate the death rate and the very opioid “crisis” which the restrictions are trying to abate.

The Road Ahead

The future of lifting opioid restrictions does not seem anymore bright, as the Trump Administration will likely continue the failed policies of drug interdiction that have plagued this country since the 1960s. The DEA recently announced that they will be reducing the supply of prescription opioid painkillers in 2018 by 20 percent, which will only continue to exacerbate opioid deaths and decrease the welfare of pain patients who desperately need treatment. According to public comments offered while this policy was under review, this new plan could prove harsh for many Americans. One potentially affected patient comments, “[t]he only medicine that has made it tolerable for me to live is Methadone daily & Oxycodone for breakthrough. I would have killed myself several years ago had I not had access to a pain clinic to prescribe & monitor my pain.”

By limiting access to prescription opioids, the federal government is not only forcing citizens to endure chronic pain, but also driving them towards a black market that is more dangerous than the initial concern. Therefore, policy should expand access to opioids, in order to allow patients to be rightfully treated under the care of a physician. Prohibition has not succeeded in curbing overdoses nor significantly discouraging drug use, for street drugs are still easily obtainable. Instead, modern policies intended to solve American drug addiction have only magnified the dangers inherent to illicit markets, fueling the staggering number of overdose deaths in the United States.

Image Credit: Wikimedia/ Adam