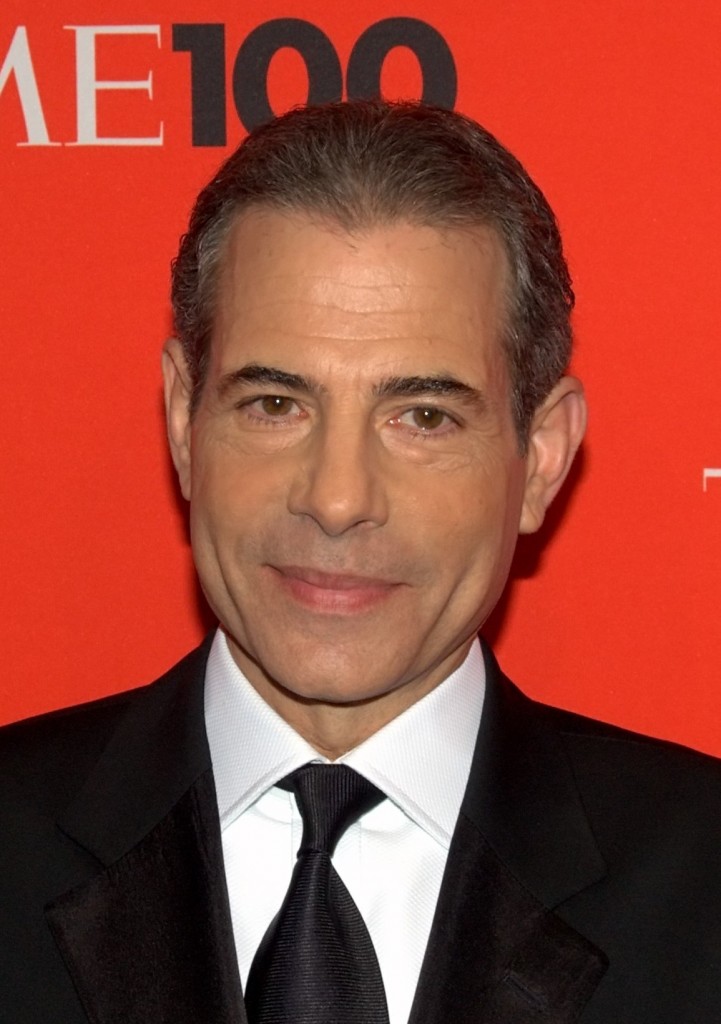

Richard Stengel is the Under Secretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs, providing global strategic leadership of all Department of State public diplomacy and public affairs engagement. After working alongside Nelson Mandela on his autobiography, he later served as associate producer for the 1996 Oscar-nominated documentary, Mandela. As former managing editor of TIME and Time.com, Stengel received a 2012 Emmy award as executive producer for TIME’s documentary, “Beyond 9/11: Portraits of Resistance.”

Harvard Political Review: Some have said that the United States is being “out-communicated” by potential rivals ISIL (Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant), Russia, China, and Iran. What’s your take, and how has the shifting state of communications in the 21st century complicated your efforts to communicate with foreign nations?

Richard Stengel: So, our communication isn’t just government messaging. If you look at all the media and content that’s created by America, that’s what I look at as our messaging…. Our messaging and content dwarfs everybody else’s. Our government content is just a tiny percentage of that. Look at the amount of what ISIL does on social media every day, so let’s say around 50,000 to 60,000 pieces of content. Taylor Swift gets retweeted 3 million times a day. That is more content than ISIL does in a month. So, not that there’s a one-to-one correspondence, but I think this argument that we’re being “out-competed” is deeply, deeply flawed, in part because people are not looking at the whole waterfront of content.

HPR: Some of your duties include overseeing the Center for Strategic Counterterrorism Communications (CSCC). Which recently developed technological strategies do you use to perform counterterrorism successfully?

RS: One of the things that’s happened over the last few months is that we’ve had a process of dynamic change and evolution of CSCC, which is the organization you mentioned, to become something which is called the Global Engagement Center. And the idea comes from this kind of central insight that, you know what, we’re actually—in this space as counter-ISIL—not necessarily the best messenger for the message we want to send. Who is the best messenger? People who have credible voices, like mainstream Muslims who are out there saying that Daesh is not legitimate Islam. So what we want to do is get away from the business of direct counter-messaging by the government to helping amplify and optimize the content of people who are credible voices against Daesh. And we’re seeing this great growth of counter-Daesh messaging among people all around the world. We want to help that.

HPR: How would you describe the state of modern communications with the public given that we are in an increasingly digital age? Have any technological developments significantly impacted your work with transparency, particularly with regard to President Obama’s administration?

RS: Well, absolutely. I mean, if you look at the number of people at the State Department who are on social media, on Twitter, on Facebook, it’s grown exponentially. One of the things that I’ve been trying to do is to help people do that. We’re in the midst of a modernization project for all the websites of all the embassies around the world. I constantly advocate for ambassadors to be on Twitter and Facebook, and I think we’re seeing a new kind of digital communications strategy on the part of the State Department that’s really having a positive effect. People see that we’re the country that actually interacts with you. We have a conversation with you; we value your opinion. And I think that is a core American value.

HPR: Before assuming your current position, you were the managing editor of TIME magazine and Time.com. How has your journalism background come into play with your new duties in the State Department?

RS: It helps because, first of all, I understand media and how to interact with media. I understand storytelling and the power of good storytelling. I understand fact-based communication and not disinformation or misinformation. So, I think the government using some of the tools and capabilities of the private sector to enhance our own messaging and content is a great thing. It’s a wonderful thing, and I always encourage more private sector people from media and technology to go into government because I think folks like that have a really important role to play.

HPR: You collaborated with Nelson Mandela in writing his autobiography. What was that experience like, and have any takeaways from that experience impacted your life today?

RS: Yes, it was, really in some ways, the most wonderful experience of my whole life. Not to mention, I met my wife while I was working with Nelson Mandela—and she’s a South African—and my two sons spent time with Nelson Mandela while they were little while he was still alive. The idea of working with him, of trying to internalize his voice as you do when you’re working with someone on their autobiography, is just a fantastic thing. I mean, if you say to yourself everyday, “What would Nelson Mandela do?” I promise you’ll be a better person. So in some small way, I’d say it has helped me to be a better person.

HPR: What advice do you have for young people interested in entering politics in today’s world, which has become increasingly charged with media scrutiny and technological “digging”?

RS: I really encourage young people to go into public service of some kind. When I was editor of TIME, we did an annual national service issue where we encouraged people to do a year of service between high school and college. Of course that can come any time, and it doesn’t even have to be young people. I really think it’s the responsibility of citizens in a democracy to make it go, and one way that you can make it go is by getting involved with public service, however brief or however long. And one of the great things about our country is you can go back and forth. I mean, you can be in the private sector, you can go into government or public service, and you can go back. I just think that makes both realms more powerful.

HPR: In the “digital age,” mistakes have a tendency to follow you and gather attention from the public. Across your career, have you made any mistakes that had significant consequences because of the prevalence of technology in the media? What did you do for “damage control,” so to speak?

RS: Well, I’ve made many mistakes. I’m not one of those people in public life who say, “I have no regrets.” I have plenty of regrets, and you know, I’ve made a lot mistakes on social media. I’ve been taken to task for things. But again, that’s the idea, that we are, as government people, able to have a conversation and say, “Hey, I made a mistake,” or “Sorry about that….” I think that teaches people something about us as a people and as a government. I’ve made plenty of mistakes, and I’m sure I’ll make more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Image source: Wikimedia/David Shankbone