Shortly after his untimely death this spring, Alex Tizon became famous for his Atlantic article “My Family’s Slave.” The article, garnering both acclaim and criticism, has launched the deceased author into the national spotlight. Tizon was a prolific writer: in 1997 he won a Pulitzer Prize for an investigative report exposing the corruption behind a federal housing program for Native Americans. Seventeen years later, he published his memoir, Big Little Man, detailing his exploration of Asian American identity and masculinity. In exploring identity, Tizon used his experiences as a Filipino immigrant to show discrimination faced by the larger Asian American community (discrimination which is largely ignored in American society). However, Big Little Man’s focus on East and Southeast Asian Americans, as opposed to all Asian Americans, exemplifies how South Asian experiences are erased in discussions of Asian American identity—a phenomenon that extends well beyond this one book.

Big, Little, but not South Asian

Tizon tied together his memoir’s two major themes—Asian heritage and masculinity—in his chapter on wen wu. Wen wu, he explained, means that the ideal man is not only physically strong (wu), but also intellectually and emotionally strong (wen). The concept originated in China, and spread to other neighboring countries. Tizon argued that wen wu is a major contrast between Asian and Western notions of the ideal man, and contributed to the feminization of Asian men in American culture. He imagined that “the badass cowboy-soldiers of the West made an assessment of the Chinese with their gowns and braided queues, their reserved demeanor and soft-spoken ways, and they came to their conclusions … Wimps, that’s what they are.”

The feminization of Asian men is an important problem in American culture, and contributes to the systemic oppression faced by this group. In the chapter “Tiny Men on the Big Screen,” Tizon examined Asian and Asian American men starring in U.S. movies and TV shows, finding that neither are allowed to embrace sexuality like white characters. The culmination of a romantic relationship is at most a hug—though it rarely even reaches that point. More often than not, Asian men are not even cast in lead roles. Instead, they are portrayed as desexualized and frail sidekicks used to make non-Asian stars look bigger and more powerful. The result is a pervasive undesirability of Asian men. The root cause, according to Tizon, is wen wu.

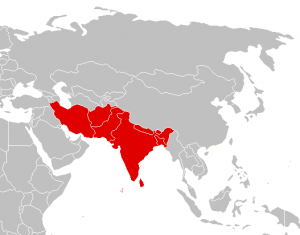

In some respects, South Asian men are feminized in the same ways as East Asian men, but Tizon ignored these perspectives by focusing on wen wu. He noted that wen wu spread to East and Southeast Asian countries, and not South Asian countries. Wen wu is not the sole contributor to Asian men’s feminization by Western culture. Tizon focused too heavily on wen wu as the single reason for pan-Asian male emasculation in the West, and thus erased the experiences of South Asian men. He should have either acknowledged the complexity of Asian masculinity, especially when combined with the post-9/11 racism towards South Asians, or explicitly defined his focus on East and Southeast Asians.

Tizon’s attribution of wen wu to the Asian male experience ignores American society’s complex perception of South Asian masculinity. In some ways, South Asian American men are seen as feminine as other Asian American men. In his book Stranger Intimacy, University of Southern California professor Nayan Shah describes how South Asian men were ridiculed by whites for their clothing and their long hair wrapped in turbans, similar to the contempt for East Asian men’s long hair. This perception is reinforced by the media; in the TV show “Master of None,” Aziz Ansari’s character Dev Shah is repeatedly described as “little” by both himself and other characters. In the preface to their book Communicating Marginalized Masculinities, Professors Ronald L. Jackson II and Jamie Moshin assert that “U.S. representations of Indian men characterize them as heavily accented, nerdy and F.O.B. (‘fresh off the boat’),” though they also note that Indian men are sometimes hypermasculinized. This sweeping view of South Asian masculinity finds its roots in Britain’s colonization of India, the boundaries of which encompassed other modern countries like Pakistan. During this time, British men hypermascunilized Sikh men to recruit them as soldiers and emasculated Bengali men to gain control over them, Rajini Srikanth, University of Massachusetts Boston Professor of English, told the HPR.

The colonial legacy, however, has changed in America. “Particularly in the post 9/11 period, I think being brown has really come to mean different things in this country,” said Asha Nadkarni, University of Massachusetts Amherst Professor of English, in an interview with the HPR. “South Asian Americans then were suddenly racialized in a way that was different—racialized as more threatening.” In Big Little Man, Tizon highlighted various examples of positive associations with the color yellow to contrast the weakness associated with yellow skin. He noted that “Hindus in India wore yellow to celebrate the Festival of Spring.” Tizon used South Asian culture to promote yellow skin, yet failed to acknowledge the brown skin of South Asians, as well as the deadly consequences of that skin color in post-9/11 America; in essence, he exploited the South Asian experience.

Tizon used wen wu to explain other significant aspects of Asian identity, such as educational attainment. In examining the large number of Asians found on college campuses, he wrote that “the ideal of wen, combined with the traditional Confucian ethics of sacrificing for long-term goals and subordinating personal drives for a greater good, contributes to Asian Americans’ attaining on average higher educational levels than any other group.” Tizon himself admitted that “Indians are now the second-largest foreign student population in America,” and 32 percent of Indian adults in the U.S. hold a bachelor’s degree. The Educational Longitudinal Study, a national survey of high school students, reported that 84 percent of fathers and 62 percent of mothers of South Asian children had graduated from college. For parents of white children, the rates were 40 percent for fathers and 33 percent for mothers. South Asians are well educated, which makes it reasonable to assume that South Asians are included in Tizon’s earlier description of Asian Americans seeking higher education. Why does Tizon only mention wen as a factor for Asians’ high educational attainment? Tizon should have limited his scope by acknowledging wen wu only applied to some parts of Asia, which would signal his recognition of different Asian experiences.

Perhaps his most egregious error is that while Tizon repeatedly ignored South Asian challenges and experiences, he felt comfortable in claiming the region’s accomplishments. He wrote that he wished his U.S. education had taught him about Asian triumphs throughout history, like the Filipino ruler Lapu-Lapu’s successful resistance of a Spanish invasion in the 1521 Battle of Mactan. He pointed to South Asian accomplishments, noting how in the 5th century CE, “Asia—with China and India as hubs—was by far the most advanced, cultured, and commercially vibrant continent on the planet.” He would go on to assert that from the 15th century “up until the early 1800s, China and India together accounted for half of the global economy.” It is hypocritical of Tizon to lament America’s ignorance of Asian accomplishment and fail to mention challenges faced by South Asians.

Other chapters of Big Little Man are no more inclusive. One is largely devoted to explaining sex tourism, during which (mostly Western) men travel to other countries in order to have sex with local women. While he discussed this phenomenon in East and Southeast Asian countries, like the Philippines, Thailand, and Cambodia, Tizon ignored its occurrences in South Asia; the U.S. 2013 Trafficking in Persons Report notes the unfortunately widespread practice of trafficking Nepali and Bangladeshi girls in India. Furthermore, he cited American author Boyé Lafayette De Mente’s explanation that Western men are attracted to these women because they are “small-bodied and delicate-appearing.” Tizon noted that this excerpt comes from De Mente’s book Bachelor’s Japan, and yet attributed this description to “the Asian woman,” applying Japanese characteristics to all of Asia. It’s ironic that one of his chapters is named “One of Us, Not One of Us” to describe the nature of being American and yet feeling like an outsider. The name is similar to Srikanth’s book on that very feeling in the context of South Asian Americans in the Asian American community: A Part Yet Apart.

From Apu to Dev

The erasure of South Asian experiences in larger discussions of Asian American identity is a pervasive phenomenon, perpetuated by the media. A rough analysis of major media outlets found that, among Asians, East Asians are disproportionately represented compared to their population rate. Meanwhile “brown Asians”—South Asians as well as Vietnamese and Filipino populations—are largely ignored. In the Netflix show “Dear White People,” the East Asian character Ikumi introduces herself as “your new catch-all Asian friend.” Her comment makes fun fun of the way that many cannot distinguish between Asians, even if they are from different countries. Ironically, the show criticizes those who group Asian Americans together while doing the same. Perhaps Ikumi’s joke would be more revolutionary if there were a non-East Asian representative of the Asian Student Alliance, or if the only Indian character in the entire show had not creepily hit on a main character.

When South Asian American characters do appear in the media, they are often subjected to tired stereotypes instead of experiencing a full range of human emotions and experiences. Both Srikanth and Nadkarni recalled Apu from “The Simpsons,” a constantly-polite, workaholic supermarket-owner. There are always “7-Eleven clerks and gas station owners,” Srikanth adds. Nadkarni recalls the fourth episode of “Master of None” in which Ansari’s character, Dev Shah, auditions for various acting roles. One role is to be a cab driver with an Indian accent. He refuses to do the accent, and unsurprisingly, doesn’t get the part. He also auditions for a TV show that is casting three, fully developed characters. Then he sees an email where one producer says that the network cannot cast two Indian leads, even though Ansari and another Indian actor were perfectly qualified. “That [episode] sort of says it all,” Nadkarni said.

The last, and deadliest, stereotype of South Asian Americans is that they are all Muslims, and therefore must be terrorists. Though wrong on both counts—South Asian Americans practice a variety of religions, and Islam does not promote terrorism—the stereotype is still prevalent. Since 9/11, South Asians have been perceived as more hostile because “there is a conflation of being South Asian with being Muslim,” Srikanth said. In 2001, a man in Texas wanted “to retaliate on local Arab Americans, or whatever you want to call them,” so he murdered two South Asians, one Hindu and one Muslim. There have been more than 800 hate crimes committed against brown people since 9/11. If the Asian American community wants to keep using the term “Asian American,” it needs to address the skyrocketing deaths of a significant demographic in the group. And to do that, it must acknowledge that South Asians exist. There is some progress: though Tizon’s book never mentions this problem, Asian-American organizations have. In February 2017, a man shot two South Asian men, killing one of them, because he believed them to be Middle Eastern. The Asian Pacific American Labor Alliance circulated a press release expressing sympathy for the victims, which included a call for greater support for South Asians from the broader Asian American community. The Asian American Legal Defense Fund also has a program dedicated to supporting South Asians targeted by racial discrimination after 9/11.

Beyond Borders

One remedy for South Asian erasure is for the term “Asian American” to be widely understood as including all types of Asian experiences. “What South Asian Americans have done is really, for the last 25 years, pushing Asian America to interrogate its own boundaries,” Srikanth said. This has been especially prevalent in academia, she said, as Asian American Studies professors have fought to include South Asian perspectives. However, South Asia is not the only region that is struggling for recognition in this term. “What Europeans and Americans call the ‘Middle East’ is actually ‘West Asia,’” Srikanth explained. “Where do conversations about Palestinians fit into Asian America? What do we think about Iranians?” These questions are coming to the forefront of Asian American Studies.

Another solution is to use “Asian American” as a way of uniting different communities, instead of as an all-encompassing term to homogenize many peoples. In Asian Americans’ everyday life, Srikanth explained, people usually identify more with their specific country of origin than with the broad term “Asian American.” The term, she said, “is a pan-ethnic label that brought together very disparate ethnic groups: Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Korean Americans, Filipino Americans. It by itself is a coalitional construct.”

The term “Asian American” is more powerful in its coalition-building context than as an identity label. Embracing that context will not only make it easier to acknowledge the diversity of the groups united by that phrase, but will also advance racial equality. Asian Americans from all regions are subjected to the “model minority myth,” a stereotype painting them all as well-educated, hard-working, rule-following, and part of “solid two-parent family structures.” Asian Americans are then pressured to conform to given characteristics. If they fail, their ethnicity is then stripped from them; South Asians who do not live up to the model minority myth are often classified as black, which also perpetuates negative stereotypes about African Americans. Deconstructing the model minority myth is a necessary step towards acknowledging the full humanity and diversity of Asian Americans. And to do that, all of us, especially those with powerful voices like Alex Tizon, must first expand our narrow image of what it means to be Asian American.

Image Credit: Vervictorio/Wikimedia Commons