A college library bookshelf.

The Great Works

“We absolutely never explicitly talked about race in my English classes. I do remember in my senior year class saying something to my classmates about what it’s like to be the only black person when we’re talking about slavery or racism, but I had a largely joking tone and the conversation didn’t extend beyond a few minutes.” Jenna Gray, a Harvard junior, went to “a nearly all white, private Catholic all girls’ school,” where she felt silenced and, in turn, made into a spokeswoman for her race. Her experience is not an uncommon one for students of color.

Unfortunately, neither is Gray’s lack of exposure to diverse literature within the English classroom. Traditionally, high schools focus on teaching the books that are known as “the great works” or “the canon.” Not every high schooler reads every book in the canon, of course, but at schools across the nation, students are expected to be familiar with works like Romeo and Juliet and The Great Gatsby when they graduate. Regardless of a school’s socioeconomic, cultural, or racial demographics, its curriculum is likely to be made up of books like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Scarlet Letter, and Catcher in the Rye.

These books share several traits: they were all written by white, heterosexual, dead males. They are also all widely regarded as literary classics, featured on lists like The Guardian’s 100 Greatest Novels of All Time (except Romeo and Juliet, since it’s a play). While these books have literary merit and provide high school students with shared cultural references, the homogeneity of their authors and characters provides a canon that fails to cater to a heterogeneous audience.

Questioning the Canon

A 2016 Scholastic study reported that 58 percent of kids aged six to 17 enjoy reading for fun. A quarter of these same children, however, report reading for fun less than once a week. Part of this discrepancy may come from the trouble that 41 percent, especially older ones, have finding books that they enjoy. While young children “just want a good story,” the older ones who struggle to find interesting books increasingly mention their desire for characters who do not fit into a mold. Eleven percent want ones who break stereotypes, 13 percent want someone who is differently-abled, either physically or emotionally, four percent want an LGBTQ character, and 11 percent want a culturally or ethnically diverse person.

Half of all school aged children are non-white. Of children’s books published in 2013, though, only 10.5 percent featured a person of color. In 2016, this number doubled to 22 percent, but white is still the “default identity.” James Qin, a junior at Johns Hopkins University, says that in high school he “always assumed that people [in books] were white, unless otherwise specified.”

Perhaps more troubling is the fact that only 13 percent of children’s books’ authors in 2016 were people of color. This does not just mean that the writing field lacks diversity — it also means that many authors who write books featuring characters of color are not of color themselves. It is not hard to imagine how these books might fail to correctly capture the existence of a person of color.

Qin explained why he never actively wanted more Chinese-American characters as a kid: “All the Asians I’ve really read in regular books tend to be very stereotyped.” Representation of Asian characters misses the mark, Qin believes, because “these books were written by white people.”

Philip Nel, author of the Was the Cat in the Hat Black?: The Hidden Racism of Children’s Literature, and the Need for Diverse Books, spoke to the Washington Post about this problem. “Representation is about power. If you’re mainly reading books about straight white boys and men, the message you receive is that straight white boys and men are — and should be — at the center of the universe.”

Unfortunately, the story does not improve very much as children move on to high school.

“Schools are not generally on the cutting edge of social movements,” Stan Karp, an editor for the magazine Rethinking Schools, told the HPR. Karp says that “sanitized conceptions” drive curricula, and that a “really rich diverse curriculum is not suitable to be assessed and is at odds with a standardized curriculum.” In a country whose schools are driven by programs like No Child Left Behind and the Common Core, it’s not difficult to see which type of curriculum — diverse or standardized — is posed to win.

A New Canon

Teachers across the country are fighting back, though. Joshua Harding, an English teacher at Park East High School in New York City, spoke to the HPR about the importance of reading diverse books. “I like the idea of literature as a means to increase freedom,” Harding explained, describing his classroom as a place where students can develop a capacity for understanding the difference between “what we say America is and what it [actually] is.”

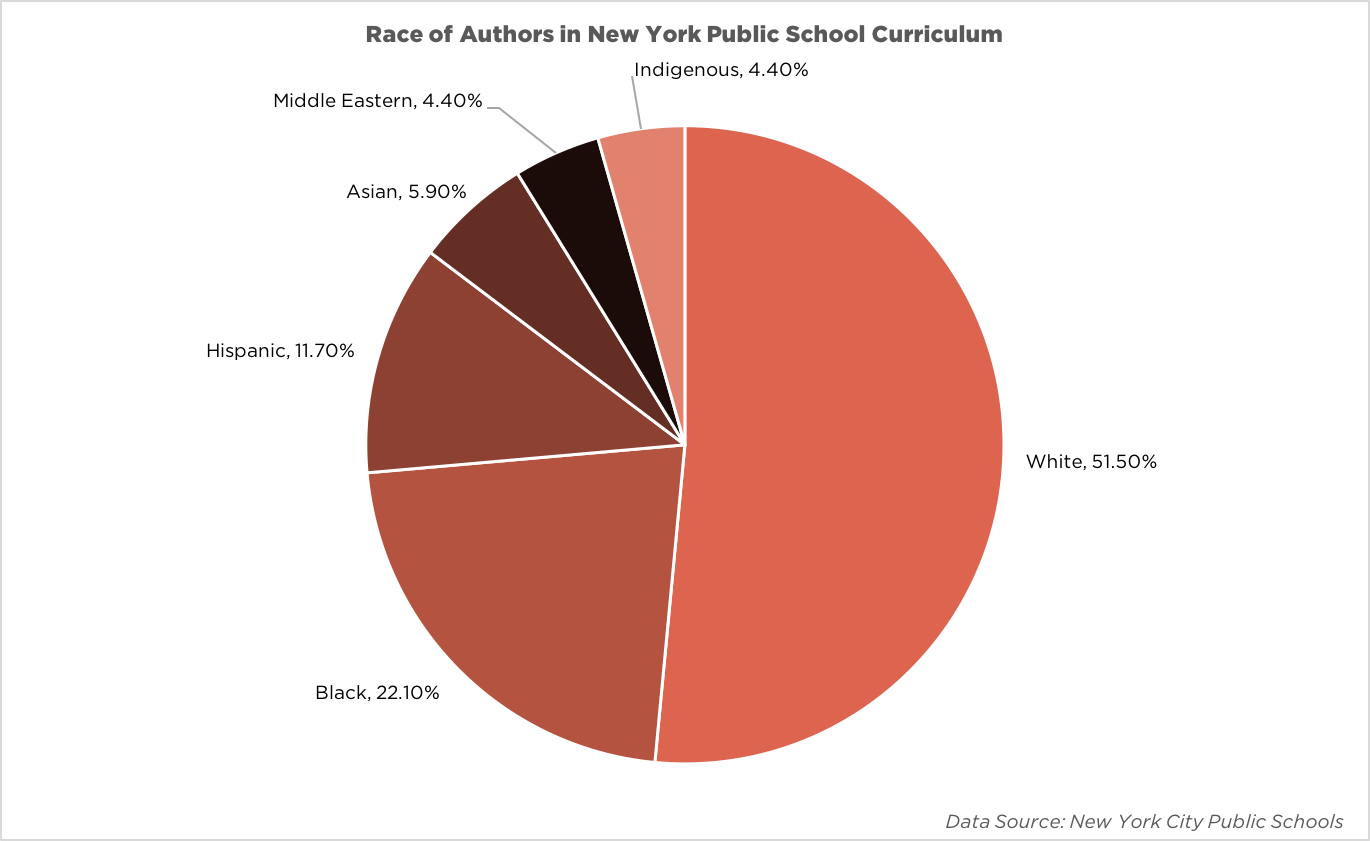

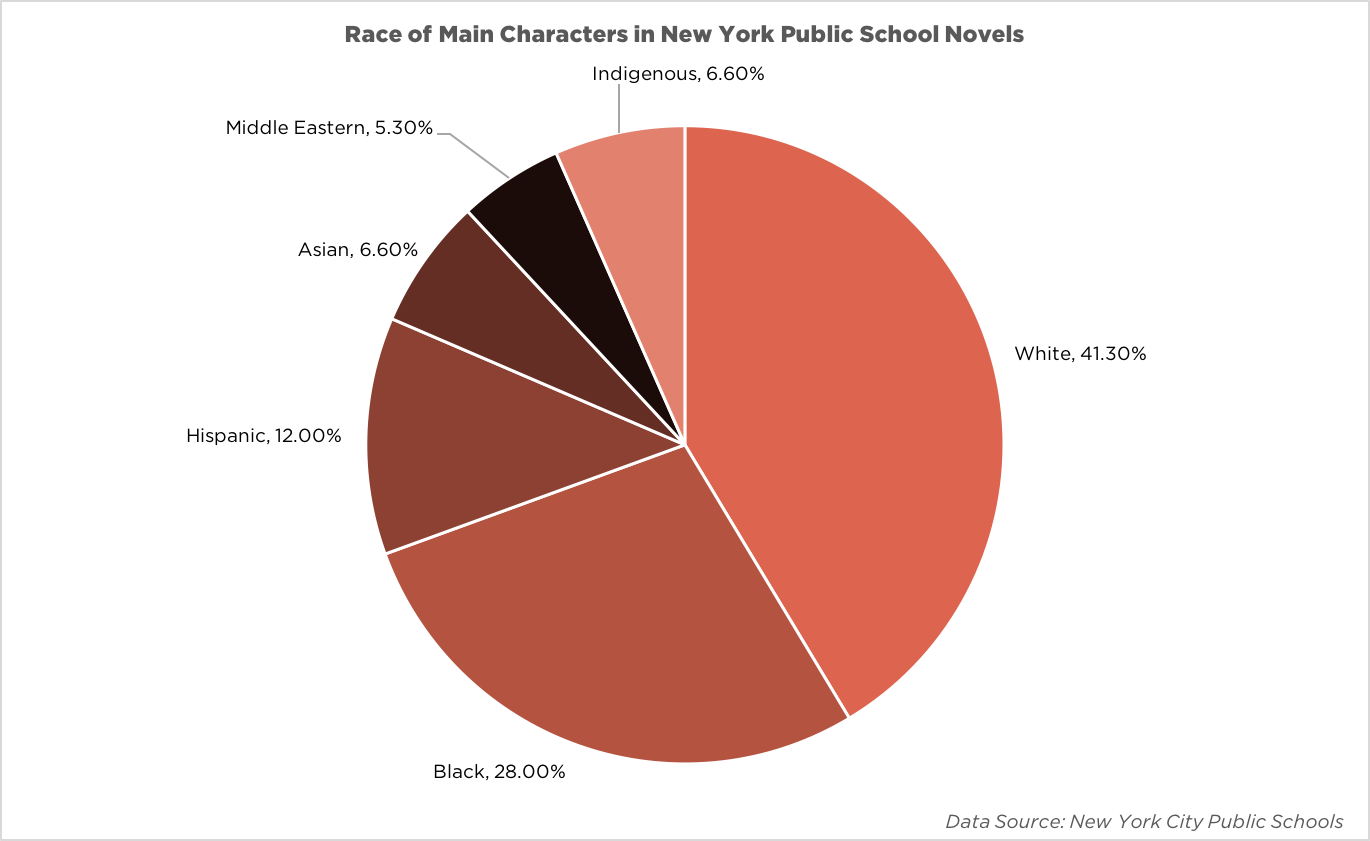

One way to see this difference is in New York City Public Schools. While only 14.9 percent of students are white, almost half of the books in the district’s curriculum feature white main characters. Furthermore, 19.4 percent of students have disabilities, but only nine percent of the schools’ books include disabled characters. While the goal may not be a precise 1:1 ratio, it is troubling that such a wide gulf exists between literature and reality.

Harding, for one, refuses to insert diversity into his syllabus merely as a token. He doesn’t have to. Harding teaches what he calls “the new canon.” Alongside Ralph Waldo Emerson and Mark Twain, his students read Frederick Douglass, Zora Neale Hurston, Harvey Milk, and Julia Alvarez. Harding says he does still assign traditional authors because students “would lose some cultural capital without it.”

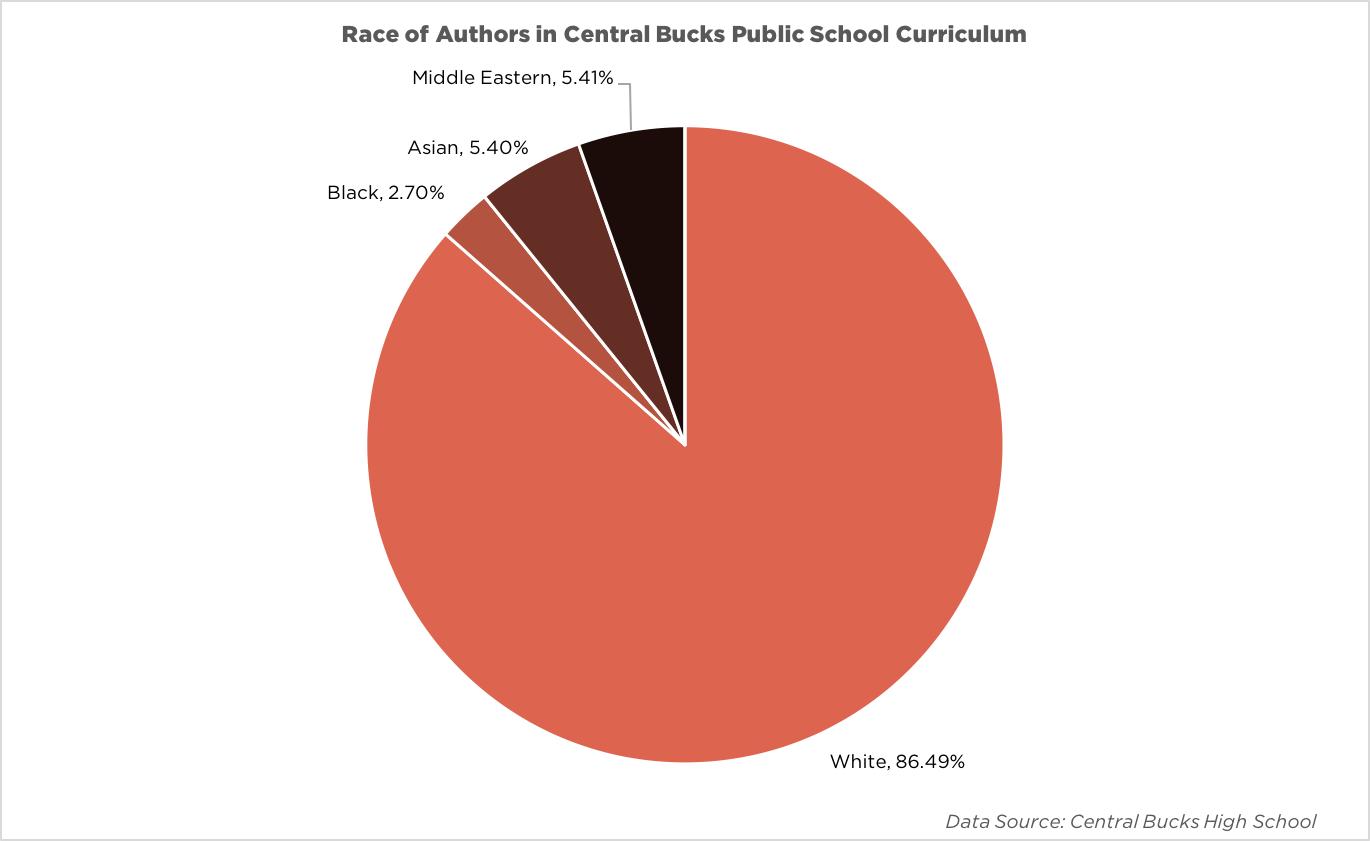

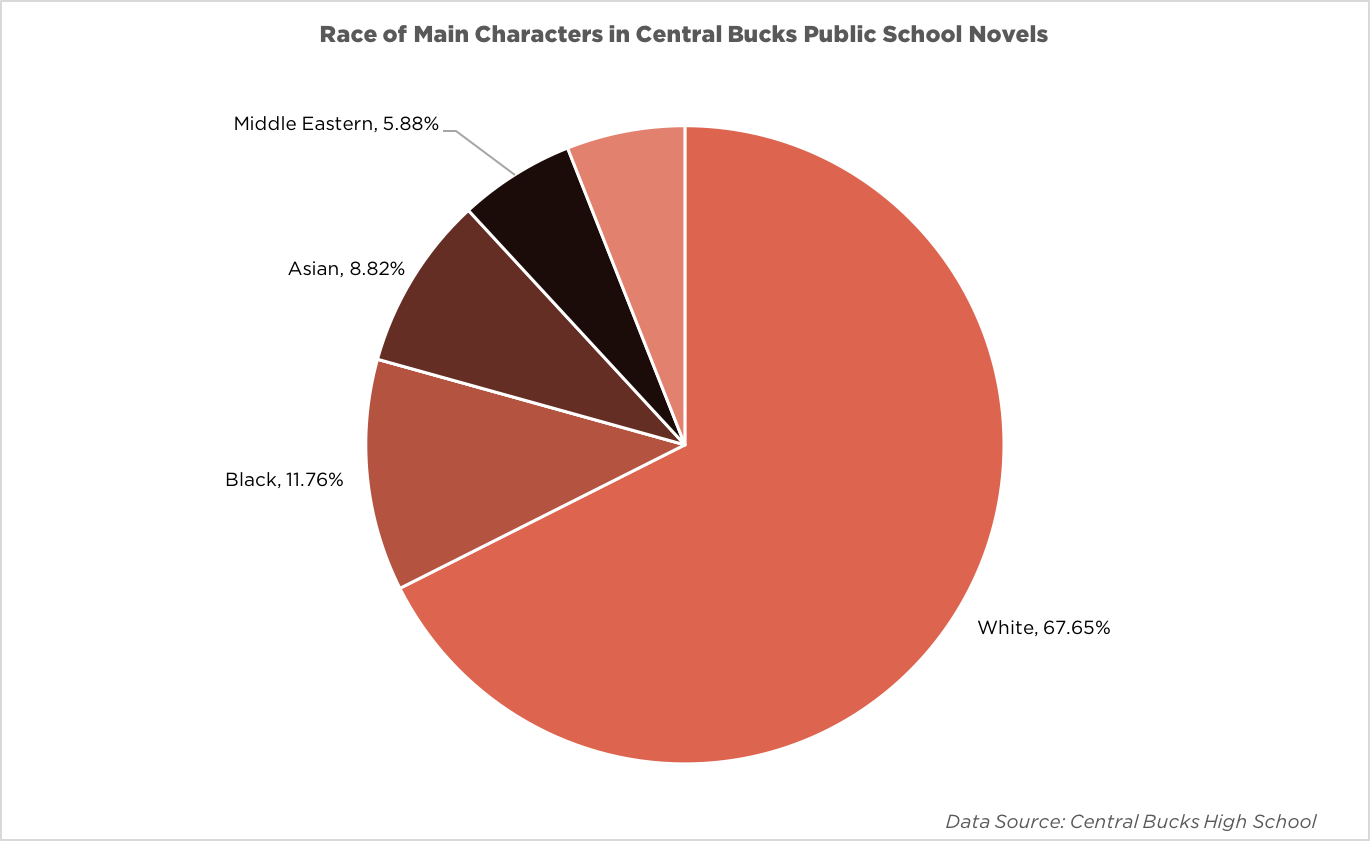

Even in schools with much less diversity than Harding’s, some teachers are fighting back against ethnically and racially homogenous literature. Kim Koch, an English teacher at Central Bucks High School in Philadelphia, is pushing to get new books approved in her school’s curriculum. Central Bucks, where Koch teaches, is 92 percent white. But she still sees a problem — at least “eight percent of our students don’t see themselves” in the books they read, Koch explained, because “between 10th and 12th grade, every single author is a dead white man.” Koch refuses to disregard lack of representation simply because her school is less diverse than many others. Over the past three years, she has created a list of 46 books featuring characters of color, and she hopes that she and other Central Bucks teachers will begin to bring some of those novels into the classroom. Examples include Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad and Toni Morrison’s Home. In an interview with the HPR, Koch, who has a master’s in African-American Literature, stressed the importance of literature that depicts cultural diversity in the present day, not just in historical contexts. ”They know black people were slaves 150 years ago. That’s not what we need.”

Koch has found that students are largely receptive to reading lists that include greater diversity. When she introduced African American literature into her senior English class, students of color reacted positively; one explained to Koch that the books helped students “understand that she comes from a different experience than they do.” This sort of change is precisely the point of Koch’s push for more books that center characters of color. “We want to prepare [students] to live in a global society,” she argues, and diverse literature is a key component of that sort of education.

Terms like ‘diverse’, furthermore, are often vaguely defined, meaning that anything that deviates even slightly from the norm is seen as sufficient. Ilian Meza-Peña, a graduate of Kipp King Collegiate High School in San Lorenzo, California, expressed frustration at the erasure of diversity within marginalized groups. During senior year, a novel by Junot Díaz was on the reading list, perhaps in an effort to include more authors of color in the school’s curriculum. However, Meza-Peña, a Mexican-American, “didn’t really relate, because [Díaz is] Dominican and writes from the perspective of Dominican immigrants on the east coast,” a subject that is no more relatable to Meza-Peña than the stories told by those dead white men.

Vicki Jacobs, a professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, spoke to the HPR about the meaning of the term ‘canon.’ Who we describe as part of the canon is “always political,” she says, echoing Nel’s sentiment that representation in literature is about power. Jacobs doesn’t recommend limiting the traditional canon, but does believe that English curricula fail when the novels they include do not offer “universal understanding about humanity and self.”

Rethinking Representation

Many of the books taught in Barbara Maher’s 11th and 12th grade English classes do just that. Maher teaches in rural, eastern Oregon at Crane Union High School. Harney County, in which CUHS is located, has only about 1,100 school aged children. Madeline Dorroh, a junior at Harvard, attended CUHS; her graduating class had eight people, not all of whom attended college.

Maher considers the skills learned in English class to be “critical — no matter what they do, they’ll have to read and comprehend, even if it’s just a manual.” During Dorroh’s tenure at CUHS, “Mrs. Maher tried to cover some Shakespeare, Beowulf, [and] Chaucer … but in a school like ours there wasn’t a lot of wiggle room. Just getting us to read those basics was a lot.” English classes at CUHS focus on teaching writing and argumentation. This leaves Maher wishing she had more time to teach novels. Currently, her students read one or two books in class a year, though they also complete several book reports outside of class. But while the list of books that students can write reports on features nearly 200 authors, not a single one is a person of color. Harney County is 91 percent white, and unlike Koch, who strives to include authors of color even in a majority-white school, teachers at CUHS don’t prioritize diversity in literature. Maher says she “doesn’t consider [diversity] at all” when choosing her books.

Maher’s method of choosing books, however, is quite intentional. She, like many teachers, believes that if students read only a handful of books every year, they should be the books that make up the core of English literature. After all, Maher’s students read both The Old Man and the Sea and The Great Gatsby, which have appeared on every single reading list researched in preparation for this article.

Some high schoolers of color would not disparage Maher’s curriculum. Joe Choe, who graduated from Harvard College in 2017, defended his high school experience, which featured similar novels. “Even though I can’t recall many books with characters who were explicitly written [about characters who shared] my background, I do think there were plenty of characters and storylines that resonated with me in other novels.” As a result, he feels that his education “didn’t lack substantially in any way.” Dorroh, for her part, considers Maher “probably the one [teacher] who best prepared us for college” because of her emphasis on writing skills.

Despite different priorities, Maher, Koch, and Harding all hope that students will leave their classrooms with a love of literature. Koch acknowledges that to be considered as “truly well-read,” her students will have to read the “classics” eventually, and believes that her job is to ensure that they have the skills to understand those books.

In the end, balancing inclusion of diversity in literature and an ongoing focus on the traditional canon is just that: an “and,” not an “or.” More than anything, English teachers agree that their classes should teach students to love reading and should provide them with the ability to understand experiences beyond their own. We should not abandon the Western canon just for the sake of bucking tradition. The tension as well as the beauty of striking this balance is embodied by one of Harding’s colleagues, who “has a ‘no dead white guys’ rule [in the classroom] but a T.S. Eliot quote tattooed on her body.” There is much to be gained from reading traditional Western “classics,” but we must also remember to make room for marginalized voices as we reconsider what constitutes the American canon.

Image Credit: Pixabay/terimakasih0