Grasping the final balustrade of a staircase with the resoluteness of a captain at sea, Teddy Roosevelt emerges from John Singer Sargent’s portrait as an embodiment of the legacy he left behind: a tenacious leader who thundered from the bully pulpit, reshaping the country through conservation, militarization, and corporate reform. The preeminent portraitist of his time, Sargent understood well that the art of portraiture is not to paint a likeness, but an identity. Roosevelt’s commanding stature—paired with the assertive placement of hands on both the staircase and the hip—convey a sense of steely confidence and vitality. Yet, the forcefulness of his body language is carefully balanced with the steady coolness of his gaze. Taken en masse, Sargent manages to capture the features of Roosevelt in a way that allows us to recognize the president in both a physical and an emotional sense. As the head of state, the president carries a unique visual burden; his image becomes a symbol of the country as a whole. The importance of presidential imagery lies in showing us glorified characters that embody a nation’s ideals of power.

“The Ambassadors,” by Hans Holbein the Younger

(Google Cultural Institute/Wikimedia Commons)

Drawing from a Hellenistic tradition, the founding fathers imbued the American presidency with classical virtues. Early portraits, such as Gilbert Stuart’s “The Lansdowne Portrait” of George Washington, drew from a codified set of European symbols that reflected the close cultural proximity the fledgling nation still shared with its former rulers. The Lansdowne Washington, painted in 1796, can be compared with Hans Holbein the Younger’s “The Ambassadors,” a dual portrait of two French diplomats painted nearly two centuries before. The portraits show striking similarities in their compositions. Both feature civil servants poised by their desks in professional dress, surrounded by the tools of their craft: pens, parchment, books, and the like. The overlap is intentional. Just as Holbein’s portrait sought to glorify the diplomats in their professional capacity, Stuart’s Lansdowne portrait sought to insert Washington into this historical dialogue. In an effort to legitimize a new regime with the traditional trappings of power, much of the imagery of Washington was tied to the past.

“The Lansdowne Portrait,” by Gilbert Stuart

(Google Cultural Institute/Wikimedia Commons)

From a narrow catalogue of images crafted during the early years of the presidency, one can see the ideals of the office take shape. The Lansdowne Washington set a precedent; its classical portrayal of the president as a dignified, reserved, and able statesmen would be emulated in the portraits of presidents from James Polk, Millard Fillmore, and Franklin Pierce to George H.W. Bush and George W. Bush. Other archetypes were set around the same time. Jefferson’s seated portrait, painted by Stuart, embodied a Republican chastity and “everyman’s man” persona that would be referenced by John Quincy Adams, John Tyler, Grover Cleveland and Franklin Roosevelt. These recurring themes are critical markers of the development of American democracy. Although heavily influenced by European trends, American iconography rejected the aggrandizement of royal portraiture and rather came to be codified through the plain, approachable statesman. The qualities of democratic leadership were defined through early portraiture, disseminated from grand canvasses to the faces on a dollar bill.

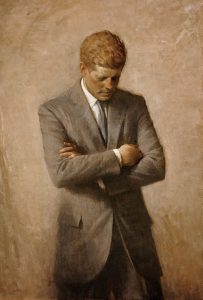

“Portrait of John F. Kennedy,” by Aaron Shikler

(White House Historical Association/Wikimedia Commons)

As the nation has evolved over the years, so have our images of our leaders. The selfless civil servant has become a showman. Whether one turns to Aaron Shikler’s introspective Kennedy, head bowed in contemplation, or Chuck Close’s clownish distortion of Clinton’s face, the modern portrait inverts the traditional effort of fitting the man into a role of power. Rather, today’s portraiture seeks to frame the office through the lens of each individual’s identity. With the ubiquity of media in a modern era, the official portraits of the presidents have sought to provide a unique intimacy between the audience and their leaders, sometimes abstract, sometimes vulnerable, searching. Modern portraits have broken from the old conventions, as they seek to humanize the president through individual flaws while still reinforcing authority through historical iconography.

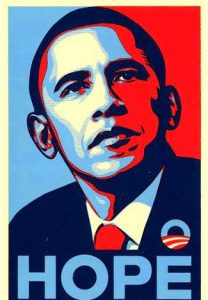

Obama Hope Campaign Poster, Shepard Fairey

(Shepard Fairey/Wikimedia Commons)

The images that we paint of our presidents tell stories of power catered to an American audience. Looking at the idealized versions of our leaders, and how those ideals have adapted over time, presidential portraiture gives insight into the men that held the office and to the development of the executive branch over time. But, perhaps most importantly, the images paint the ideals of the citizens. When Obama’s “HOPE” campaign launched in 2008, it was not just the word that sought to represent a new vision for the country, but the stylized headshot that accompanied it. In bold block colors, Obama’s campaign imagery became a new image for the future American presidency, something exciting, that broke cleanly with tradition. The portrait redefined how a president could be seen. Young and bold, it was a game changer.

Official portrait of Donald Trump

(President Donald J. Trump/Wikimedia Commons)

Weeks ago, the first official portrait was taken of Donald Trump. The optimism of 2008 was banished beneath a furrowed brow and tight lipped scowl. “Stomach-turning” was how one lawyer in the Boston immigration court—a court that has been overrun due to the burdens of Trump’s aggressive new policies—described the arrival of the portrait to the Boston Globe. Although it may be easy to discount an image of presidential power as nothing more than the likeness of a man, the language embedded in the images that have been crafted around the presidency speak to so much more. When it comes to painting a president, the portrait is not just a picture—it’s politics.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that the Lansdowne Portrait was painted in 1703. It has been updated with the correct year, 1796.