This Wednesday, June 17, is Dalloway Day – a celebration both ordinary and extraordinary. Around the world, fans of renowned modernist author Virginia Woolf will pause to celebrate her 1925 novel “Mrs. Dalloway,” a story about a single day in the life of wealthy Londoner Clarissa. As she walks through post World War I London to prepare for her party that night, Clarissa reflects on her childhood, her relationships, and her belief in human connection. Her climactic triumph of ordinary thought — an internal affirmation of personal agency, human vitality, and fulfilling friendships — remains an extraordinary moment in literature.

As Dalloway Day approaches, I’ve been thinking again about “Mrs. Dalloway’s” famous final lines, written from the perspective of Clarissa’s childhood friend, Peter Walsh:

“What is this terror? what is this ecstasy? he thought to himself. What is it that fills me with extraordinary excitement?

“It is Clarissa, he said.

For there she was.”

Clarissa’s triumphant presence at the end of the book has always resonated with me, especially as a contrast to the suicide of her traumatized double, Septimus. It’s incredible to be alive, to be present — to be there. But looking back at the novel in the midst of everything happening this year, I think that “being there” in “Mrs. Dalloway” transcends the idea of simply living in the moment. Clarissa’s journey through 1920s London and her effervescent party affirm the strength of our spiritual connections. When we feel isolated, when we feel insignificant — even when we are dead — human beings can survive and live on as the impact we have on each other.

“Mrs. Dalloway’s” idea of connection begins with Clarissa’s theory of people — a theory she devises in part to help her face her fear of death. “Since our apparitions, the part of us which appears, are so momentary compared with the other, the unseen part of us, which spreads wide,” Woolf writes, “the unseen might survive, be recovered, attached to this person or that, or even haunting certain places after death… perhaps — perhaps.”

“The part of us which appears” — the physical version of ourselves with which we’re all familiar — actually only appears for so short a time. We’re born, we live, and, soon enough, we die. But “the unseen part of us,” to Clarissa, has the potential to be something more. What is this “unseen part”? And how can it survive even death?

Woolf wrote in “Modern Novels” that her modernist contemporary, James Joyce, had attempted to “record the atoms as they fall upon the mind.” Joyce was obsessed with capturing the way a person experiences reality — with the experiential details of what it was like to walk down the street, buy a sausage, and cook it in a pan. But Woolf was interested in an even more ambitious project: with how an entire person “falls upon the mind.” What was the psychological, spiritual, and emotional impact of one person on another?

Her answer is related to the “unseen part of us” — and with how it takes on a life of its own. All of us are unique, all of us have our minds, all of us have our essence. And while nobody can ever know what it’s like to be inside another person’s head, we also have our moments of closeness together. We are intimately connected after a meal, Lady Bruton feels in “Mrs. Dalloway,” “as if one’s friends were attached to one’s body, after lunching with them, by a thin thread.” When Richard can’t find the words to tell Clarissa that he loves her, “she understood without his speaking.”

When we are apart, moreover, we retain the memories of each other, the impressions we leave on one another with every interaction. “The unseen part of us” lives on in the impressions by which other people, consciously and unconsciously, remember us. It survives in the multiple versions of ourselves that reside within the hearts of our friends. Our living selves are short-lived compared with the impact we have on others — with the real but invisible legacy we leave that is transmuted onward, again and again, through the unseen parts of other people. Through this impact, it is possible for Clarissa to feel “part of people she had never met; being laid out like a mist between the people she knew best. … It spread ever so far, her life, herself.”

When I first read “Mrs. Dalloway,” I assumed that Clarissa enters the room in the novel’s final line. But now I think she was already there. The party winds down to a close. Clarissa’s guests make their way to the door. As Peter Walsh sits on the couch, a powerful sensation overwhelms him: “What is this terror? What is this ecstasy? What is it that fills me with extraordinary excitement?

“It is Clarissa.”

Whether or not she does physically materialize, Clarissa “is there” in that moment for us, too, as readers — as is Virginia Woolf. The unseen part of them survives within us nearly a century after the publication of “Mrs. Dalloway.” Virginia Woolf and her immortal protagonist live on as the joy we take in their work, as an empathy for the lives of others, and as a passion for life, love, and friendship.

And they survive as the choices we make with their theory in mind. It’s amazing to think that what we do in this life will matter after we’re gone, but it is also quite daunting. Virginia Woolf reflected on the beauty of that challenge in “A Sketch of the Past.” “It is a constant idea of mine,” she writes, “that the whole world is a work of art; that we are parts of this work of art. Hamlet or a Beethoven quartet is the truth about this vast mess that we call the world. But there is no Shakespeare, there is no Beethoven; certainly and emphatically there is no God; we are the words; we are the music; we are the thing itself.”

Virginia Woolf’s art still resonates with us many years after her death. I believe in its message that our lives can do the same. As we keep our distance during the coronavirus, the spiritual bonds between us ensure that we are neither forgotten nor alone. As we mourn the death of George Floyd and the countless others who have lost their lives to police violence, their memory inspires us to fight for justice and equality. This Dalloway Day, close your eyes. Imagine the thousands of faces who have had an impact on your life.

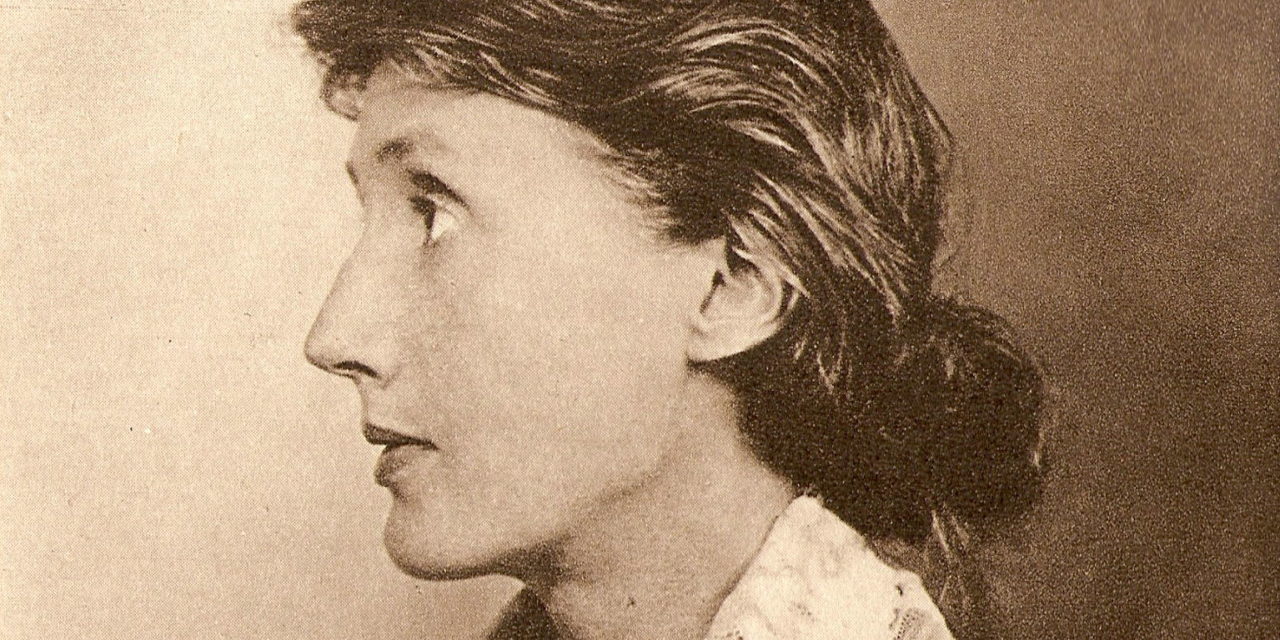

Image Credit: “Virginia Woolf, circa 1920” by Petkenro is licensed under CC BY2.0