The narrative that young people don’t vote is a well-worn story. In the upcoming presidential election, though, Gen Z-ers and millennials will make up one-third of the electorate, making them a formidable political force. However, young voters typically have a turnout rate 20 to 30 percentage points lower than that of older citizens. The average voter turnout rate of 18 to 24-year-olds is generally somewhere between 30 and 45% for presidential elections and 20% for midterm elections.

A common explanation for the low turnout rate among young voters holds that young people simply don’t care enough to vote. This, however, seems unlikely: In the past few years, youth have demonstrated their political engagement through protesting, lobbying their representatives, and advocating online. In an interview with the HPR, Luke Albert, Director of Organizing of the Harvard Votes Challenge said that “one of the most common narratives about young people and college students is that we’re apathetic … about voting. And quite frankly, that couldn’t be more wrong.”

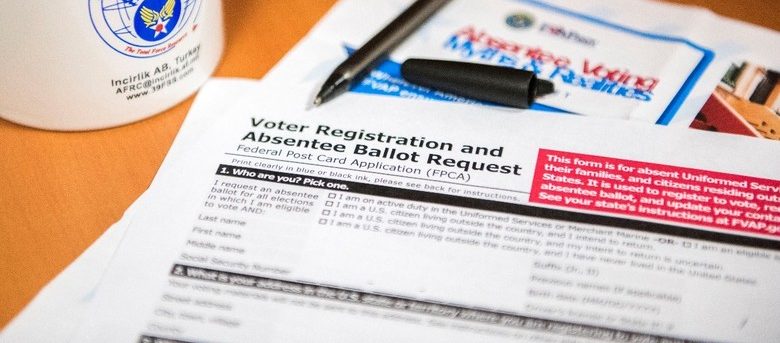

Contrary to what some may think, young people turn out to the polls less not because they are apathetic about voting but rather, because they face structural barriers to doing so. Complicated rules for absentee voting, state-by-state ambiguities, and the lack of considerations for international or undocumented students all factor into a student’s decision about voting. Fortunately, Harvard students are fighting to overcome barriers that preclude our peers from exercising their political voices. The nonpartisan Harvard Votes Challenge aims to increase awareness about elections through explanations on how to vote, person-to-person interactions, and opportunities for involvement aimed at students who cannot vote in U.S. elections. HVC’s efforts were instrumental in increasing the turnout rate among Harvard students in previous elections, and will continue to bolster the voting potential of students in upcoming ones.

Obstacles to Youth Voting

In the midst of hectic lives, it can be difficult for students to navigate the complicated rules of casting a ballot. This becomes especially complicated for students who vote out-of-state, as most Harvard students do. Varying and oftentimes complex rules for requesting absentee ballots create structural barriers that preclude students from registering and voting. Albert explained that many students feel overwhelmed as a result and may decide that they are too busy or confused to figure out the intricacies of the process.

A large part of the difficulty comes from the fact that primary and general elections are conducted on a state-by-state basis, meaning every student must follow a different procedure to make sure their absentee ballot is counted. In some states, such as Oklahoma, students can request an absentee ballot online. In others, such as New York, students must fill out and mail a paper ballot request form by a certain date in order to receive their ballot on time. For students who are not aware of the extra step, it may become too late to receive their ballot, rendering them unable to participate in an election.

Getting a ballot notarized can also be a confusing process. A notarized document is one that has been certified by an official who verifies the identities of anyone signing the document and seals it. Currently, twelve states require that absentee voters get their ballots notarized. “Students might not even know what [notarizing] means,” Albert emphasized. He did note, however, that the Harvard Campus Services, which is located in the Smith Campus Center, is a helpful resource for students who require their ballots to be notarized.

Voter Participation on Campus

Though the complexity of the process can make voting more difficult, these barriers are not insurmountable. The 2018 midterms saw unprecedented youth voter turnout rates, and Harvard was no exception. The campus doubled its participation rates from 22.4% participation in 2014 to 48.6% in 2018. Albert attributed this increase in part to the efforts of HVC. This election cycle, HVC aims to further raise that number, eventually reaching 100% voter registration, engagement, and turnout across Harvard and beyond. Though their efforts will undoubtedly be complicated by Harvard’s recent decision to move to online classes for the rest of the semester, HVC has already implemented a number of programs to help increase turnout for the 2020 primaries and presidential election.

One of their most widespread programs occurred during freshman move-in, during which, according to Albert, HVC members had up to 1,400 conversations with first-year students about registering to vote. “We want students to feel like it’s a part of the process when they move in … that helps foster the culture aspect, that voting and civic engagement are just a natural part of student life,” Albert explained. HVC has also organized stamps and envelopes in almost every house to make mailing in ballots and ballot request forms easier.

A large part of HVC’s strategy rests on person-to-person contact. For the local elections last semester, members conducted their first canvass by knocking on the door of every student who is registered to vote in Cambridge. They provided an information sheet about the issues on the table and helped students create a plan to vote. According to Albert, research suggests that verbally encouraging students to develop a concrete plan to vote on Election Day is one of the most effective ways to actually get them to do so. Another effective method is gathering pledges: students who receive a physical card reminding them of their pledge to vote right before Election Day are more likely to actually do so.

HVC was aiming for a 100% contact rate for the spring semester, which will become more difficult with the remote learning in place for the semester. Additionally, the risks of infection associated with going to the polls in the middle of a global pandemic — not to mention the number of states delaying their primary elections as a result — constitute another structural barrier that will likely affect HVC’s long-term goals. Nevertheless, members have already had thousands of conversations with students helping them register and vote for both primaries that have already occurred and elections to come.

Political Inclusivity and Engagement

Despite its focus on increasing voter participation, HVC is also committed to being inclusive of students on campus who cannot vote. They work to collaborate with and talk to student groups on campus that represent international and undocumented students to get these members of the Harvard community involved as well. “The key for us is using universal language that’s all about a willingness to participate, rather than putting a responsibility to participate on students,” Albert said.

Part of this effort involves avoiding questions about the voter eligibility of students out of respect for the sensitive and private nature of that information. Instead, HVC members simply encourage students who may not participate in an election to help spread information about voting within their communities. The willingness of students who cannot vote in U.S. elections to be engaged in politics is another indicator that youth do have a desire to be involved in the political process. For instance, according to Albert, last spring European students organized events, including an election-day watch party, to mark elections in Europe. For international or undocumented students who care about U.S. politics, they can encourage other members of their communities to vote and increase awareness about upcoming elections.

Though it is well-established that young people have historically low election turnout rates, this trend may not stem from a lack of political engagement in general, and it is likely not irreversible. Harvard students will not return to campus until the fall, but the impacts of HVC’s efforts live on. Its work has helped register thousands of students over the past few semesters and support the argument that students want to vote even though the process can at times seem overwhelming. Since the general election is not until November, efforts to capitalize on this engagement and turn it into voter participation will continue until then. Hopefully, young people will still be able to exercise their full political voice during this election cycle, despite the COVID-19 crisis.

Image Credit: INCIRLIK Air Base / Senior Airman Trevor Gordnier