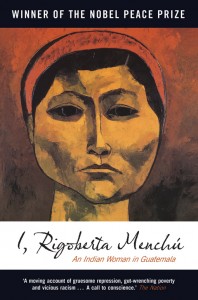

I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala

Edited and Introduced by Elisabeth Burgos-Debray

Translated by Ann Wright

290 pp. Verso Books. $22.95.

Journalists and international officials have markedly ignored the modern history of Guatemala. The nation’s past includes a long list of wrongs against the indigenous peoples of the country, including exploitation by wealthy, mixed-race landowners and government complicity in discriminatory practices. However, until the 1983 publishing of Quiché leader Rigoberta Menchú’s controversial autobiography, the attention of the world was rarely drawn to the bloodshed and activism happening in Central America.

Menchú, born in 1959, spent most of her child- and young-adulthood embroiled in not only the Guatemalan Civil War, but also the injustices against native Indians by ladinos, citizens of European and Indian descent. Inspired by her father, whom she mentions “fought for twenty-two years” to wage “a heroic struggle against the landowners who wanted to take [their] land,” Menchú took on his cause. As an adult, she began to serve as an indigenous representative and activist, motivating the oppressed peoples of her nation to participate in the civil war. Meanwhile, empowered by the support of her village, she also fought against racism, poverty, and human rights abuses. She became a central leader of the Committee of the Peasant Union (CUC) and a spokesperson for women’s rights. For her work organizing and leading the indigenous rights movement in Guatemala, Menchú received the 1992 Nobel Peace Prize, though the victory was bittersweet—at that point in the civil war, her life had already been threatened multiple times, and she was living in exile.

It was while she was living in exile that Menchú felt propelled to create a record of her story. I, Rigoberta Menchú: An Indian Woman in Guatemala, is her memoir chronicling why and how she dedicated herself to the cause of her people. Told to Elisabeth Burgos-Debray, an anthropologist who recorded Menchú’s stories and transcribed her words, the book reads as if Menchú is giving a testimony to some international court, explaining her own actions and those of an entire ethnic group: she says in the opening lines that her “story is the story of all poor Guatemalans” and her “personal experience is the reality of a whole people.” The theme of community is prevalent throughout I, Rigoberta Menchú, because it was community that initially motivated Menchú to action. She emphasizes multiple times that she is not the lone voice, activist, and humanitarian representing her people—that her parents, siblings, and many fellow Indians all fought for greater indigenous-ladino parity during and after the civil war. Consistently, Menchú stresses the importance of communal work and sharing, even—perhaps somewhat surprisingly—including ladinos in her mission to increase pay and rights for all disadvantaged Guatemalans.

While much of Menchú’s memoir is distinctively poignant and factual, especially when she describes in vivid detail the horrors of malnourishment, hard labor, and even torture, critics such as anthropologist David Stoll have cited inaccuracies in her telling of her own story. Indeed, controversy surrounds I, Rigoberta Menchú because documentation found since the publication of the memoir has indicated that she overdramatized events to create sympathy for the indigenous cause while omitting aspects of her Catholic school education, possibly to make her own stance seem more in line with Indian tradition. After all, Menchú presents herself as so dedicated to her culture that she grows up instinctively disliking ladinos and modern customs and technology because she knows “the outside world… is disgusting.” More than that, Menchú states she is completely willing to sacrifice her own life for the survival of Quiché traditions and beliefs. Stoll’s specific objections with I, Rigoberta Menchú revolve around the claim that she understates her formal education while overemphasizing or dramatizing the details of how members of her family died. True, the descriptions of how her brother and mother were tortured and killed by soldiers of the Guatemalan government are described in a manner that is meant to elicit sympathy for the indigenous movement and repugnance at the actions of their oppressors, so Stoll and other critics may be right in calling out Menchú for amplifying her story. However, the vast majority of her memoir is valid and verified, and it is not unthinkable that other Indian activists died in the manner her family members are said to have died. Said fellow writer Francisco Goldman in response to Stoll, “what rankles [about Stoll’s commentary] is the whiff of ideological obsession and zealotry, the odor of unfairness and meanness, the making of a mountain out of a molehill.”

The concerns about the memoir’s veracity beg the question of its value to the reader. The answer is merely that those who read Rigoberta Menchú’s book should treat it as yet another form of oral tradition. Just as she grew up listening to stories of her people’s culture, ancestors, traditions, and oppression, so should the reader. Like her ancestors, she “[applies] past experience to the present” in the telling of her life story; just as her “grandparents tell us many things that they’ve been witness to, things which must be passed on by their children,” Menchú is passing on the knowledge that she feels is most important for the world to know. In fact, her repeated mentions of storytelling and the passing down of wisdom, as well as her emphasis on collective knowledge, action, and credit, means that while her story is not absolutely, irrefutably factual, it is immensely valuable as a look into a culture and the mind of an activist. Menchú not only informs her readers about Indian culture—she immerses it in the richness of oral history and communal storytelling by speaking her story in a book form. So long as readers recognize it as a testimony, not a history, I, Rigoberta Menchú, is an example of Menchú’s near-complete dedication to the Indian cause and community, for she has been willing to do far more than serve as an activist and peasant organizer. Her memoir and the surrounding controversy indicate how deeply Menchú has immersed herself in her Indian identity and how much she desires to bring previously obscured indigenous history to the modern world.

Photo Credit: Verso Books