We all remember our first bookstore. The flush of colorful covers, stacked on shelf after shelf and ranging into the distance; the sound and sensation of flapping pages. The scent of espresso from the inevitably adjacent café. I’m describing my own: a Barnes & Noble in a Seattle shopping mall.

When I learned it would close in 2011, I was devastated, but not surprised. Over the past decade, bookstores across America ranging from small independent sellers to mega-chains such as Borders have faced increasingly dire financial straits. The same year that my Barnes and Noble location closed its doors, Borders filed for bankruptcy and shut down operations nationwide. This downturn is widely attributed to competition from Amazon and other online vendors, as well as the rise of the e-book through platforms such as Amazon’s Kindle.

Yet reports of the traditional retail bookstore’s death may be premature. Recent consumer data does not support the idea of a full-scale shift away from print media, but rather indicates a demand for both e-books and physical books. And given Amazon’s latest business venture—a physical bookstore—the future of bookselling may not be as digital as many think.

An Anachronism?

Amazon Books, the company’s new physical outlet, is located in Seattle’s University Village shopping center, across the street from the former site of my childhood Barnes & Noble. This seemed uniquely ironic to me. As the title of a Wired article aptly observed, “Amazon Killed the Bookstore. So It’s Opening a Bookstore.”

I was understandably reluctant to see the store for myself. Yet, I was also intrigued by the paradox of its existence: why would Amazon decide to open a retail bookstore in an age where such franchises seem doomed? Borders had been losing $1 billion in yearly income before its closing, and Barnes & Noble is currently experiencing a similar decline. In 2013, former CEO Mitchell Klipper stated that Barnes & Noble would reduce its number of retail outlets by 20 stores per year over the next 10 years, an ominous sign for the company’s long-term health.

Critics were quick to point fingers. “The reason that brick-and-mortar bookstores have been disappearing at such a rate is that Amazon destroyed their economics,” financial analyst Alastair Dryburgh pointed out in a recent Forbes article. Buying books digitally, whether through online retail or as e-books through the Kindle, is cheaper and faster than making a trip to the local bookstore. In particular, the e-book seemed to herald the dawn of a new, digital era in how consumers obtain and store their literature. As e-book sales shot up by over 1,000 percent from 2008 to 2010, analysts such as MIT’s Nicholas Negroponte forecasted that print books and booksellers would soon be shelved alongside such outmoded physical vendors as record stores and newspaper kiosks.

The Benefits of Bookstores

Did Amazon deliberately intend to kill the bookstore? If examined closely, the company’s rise to prominence seems less like a calculated takedown than an inevitable consequence of the free market. Amazon certainly heralded the dawn of a new age in bookselling, using its online presence and massive scale to drastically lower costs for consumers. Yet such practices aren’t too different from Barnes & Noble’s own strategy. “There is very little difference between big, impersonal chain stores selling books and a big, impersonal website selling books,” argued reporter Leo Mirani in a 2013 Quartz article. As much as I adored my own Barnes & Noble branch, I eventually recognized that it was only one limb of a large corporate entity—the titles it encouraged me to buy, as well as the dizzying array of products it displayed, were all part of a careful business strategy.

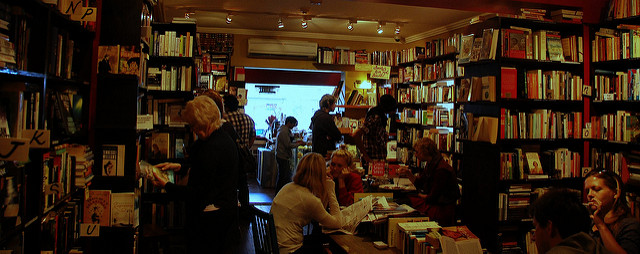

But perhaps Mirani’s judgment is too reductive. Chain bookstores, like all other physical book vendors, do offer something that online vendors cannot: an enjoyable browsing experience. I would visit Barnes & Noble to scan the shelves for new finds more often than to hunt for specific titles. And the peaceful coffee-scented ambience of my childhood is nowhere to be found within Amazon’s library.

It’s a common argument in defense of retail bookselling: even if customers end up making their purchases online or in e-book form, they need to discover them first. “Physical bookstores still serve a vital role as showcases for books,” Alexandra Petri argued recently in the Washington Post. “Their ability to bring us into contact with hundreds of things we did not know we wanted is not to be underestimated.” Independent booksellers are even better than their chain rivals at this function. Smaller and less corporate, they leverage their close connections with local communities to provide personalized book recommendations based on store employees’ or frequent customers’ testimonials.

This raises an unexpected dimension in the relationship between Amazon and its supposed retail nemeses. Without them, the site’s collection of data on market tastes is rendered relatively less useful, and the disappearance of physical books from the consumer eye may even result in a decrease in corresponding online purchases. Bookstores certainly do not need Amazon and the competition it brings, but the online giant may need bookstores in order to sustain demand for its products.

Perhaps this unique advantage is the secret behind recent consumer data, which shows a surprising return to form among American consumers: physical books and booksellers are on the rise again. After a meteoric rise, e-book sales over the past few years plateaued at around 20 percent of the market and actually fell significantly in 2015. And while chains such as Barnes & Noble continue their downward spiral, independent booksellers—their old enemies—are making an unexpected comeback. According to the American Booksellers Association, the number of indie bookstores in the United States has increased 27 percent since 2009. “The fact that the digital side of the business has leveled off has worked to our advantage,” said American Booksellers Association chief executive Oren Teicher to the New York Times. “It’s resulted in a far healthier independent bookstore market today than we have had in a long time.”

Yet indie bookstores cannot fully occupy the niche left by the retreat of large chains such as Barnes & Noble—they tend to be concentrated in metropolitan areas and literary enclaves, leaving large areas of the country without access. There are currently 2,227 in the United States according to the ABA, a number roughly on par with the number of chain bookstores in 2011. In other words, the degree to which physical book vendors will be able to retake the ground gained by Amazon and its peers remains in doubt.

Amazon Books Up Close

When I finally decided to pay Amazon’s mysterious new bookstore a visit this January, I arrived at University Village with a clear idea of what I would find upon entering: a glossy display of the year’s bestsellers, all available on Amazon’s digital storefronts for convenient online purchase. Amazon, I believed, was trying to correct a problem of its own creation—to resurrect the physical bookstore as a bare-bones showroom for its online presence. The focus, I expected, would be on advertisement over true bookselling.

I was not entirely wrong. Amazon Books was clean, well lit, and overflowing with references to the company’s digital half. Kiosks at the end of every shelf encouraged customers to price-check items—which seemed redundant, given the numerous signs and banners reminding us that all books in the store were equivalently priced to their online counterparts. In the back, a row of reading benches sported armrests with embedded Kindles— “so your children will be distracted, and you won’t have to deal with them,” quipped one customer to her friend. The center of the store was dominated by a large, Apple-Store-style display of Amazon’s various Kindle models. Even in this purportedly retail store, Amazon clearly wanted to remind customers of the digital alternative they had spent over a decade building.

As I walked through the store, though, I noticed something that I had not expected. The selection of books was far greater and more eclectic than one might find on Amazon’s front page. Moreover, each book on the shelf carried its own placard, bearing a review from a satisfied Amazon customer. Most were either four or five stars, and several were quite lengthy. They reminded me of a calling card of indie bookstores—the handwritten recommendations of store employees, providing valuable guidance for browsing customers.

This highlights one of the store’s more unique features. It draws deeply from the human side of Amazon’s website—its reviews—and presents them in a digestible, authoritative context. “Amazon has always been, implicitly, about community,” argued Megan Garber in The Atlantic. “Amazon Books is simply translating that implied community into a more immediate one.” This community, composed of millions of readers, is freely available to anyone online, but the store’s placards help integrate it into the retail browsing experience.

Amazon Books is firmly committed to promoting Amazon’s massive digital brand. Yet it is also trying to provide a rough approximation of a physical bookseller’s intimacy, using community testimonials in an attempt to overcome its own impersonality. It’s a strange compromise between the company’s warring agendas that places it outside the realm of true competition with other brick-and-mortar stores. Janis Segress, co-owner of Seattle indie bookstore Queen Anne Book Company, agrees. “I continue to be confident that independent booksellers provide something Amazon can’t, even at its first bricks-and-mortar location,” she told Publishers Weekly. Amazon Books is unique—both a showroom for the company’s original product and an acknowledgment of its own strengths and limitations as a predominantly online company.

In the end, however, Amazon Books does seem to indicate that Amazon recognizes the tremendous importance of physical bookselling. With the downfall of Borders and the decline of Barnes & Noble, it is left in a precarious position: trying to revive physical bookselling while also maintaining the digital alternative it created. Whether it can sufficiently balance these two roles to rival the appeal of its own website, my beloved Barnes & Noble, or even the resurgent indie bookstore, is still unclear—a question for the next generation of publishers, authors, readers, and literary enthusiasts.

Image Credit: Flickr/N i c o l a/LWYang