By investigating Harvard’s direct investments, Democracy Matters and Divest Harvard sought to illuminate the values implicit within Harvard’s investment in certain corporations, and how the political activities of those corporations might create discomfort among members of the Harvard community. Given this particular emphasis, Harvard’s investment in Petróleo Brasileiro S.A. Petrobras, more commonly known as Petrobras, stands out as particularly problematic.

Petrobras, Brazil’s state oil company, operates throughout the petroleum industry. According to its SEC annual report, Petrobras’s operations include refining, transporting, and marketing oil products, crude oil imports/exports, natural gas and petrochemicals; exploring and producing crude oil and natural gas; distributing oil products, ethanol, biodiesel and natural gas to wholesalers. Fossil Free Indexes determined that Petrobras possessed the seventh largest carbon dioxide emissions potential of any oil and gas company in the world. Why Harvard chose to invest in Petrobras likely stems from its extensive operations and its wealth of oil reserves, which allowed the multinational corporation to capitalize on high diesel and gas prices to amass large profits in 2012 and 2013.

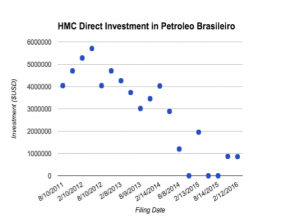

Indeed, from 2012 to 2016, SEC filings reveal that Harvard Management Corporation (HMC) invested a sum total of $46 million in the Brazilian oil corporation. As the chart demonstrates, HMC began to noticeably lessen its position within the company in late 2014. While the initial reaction might conclude that calls for divestment fueled such economic changes, the steep decline in Petrobras’ stock price provides a more convincing story. Simply, investing in Petrobras proved to be a terrible financial decision irrespective of the moral considerations.

Image source: yahoo.com/Petrobras stock

Yet, Petrobras’s corruption scandal and damaging oil spills demands that HMC recognize the moral implications of its financial investment.

A Total Wash

Petrobras became synonymous with Operation Car Wash in 2014 when details emerged of bribery, money laundering, and suspicious payments. Claimed to be one of the largest corruption scandals in Brazil’s history, the scheme involved Petrobras executives bribing construction companies and diverting most of the money to the ruling political parties. Yet, the New York Times noted that many saved funds for “Rolex watches, $3,000 bottles of wine, yachts, helicopters and prostitutes.” Brazil sought to expand its economy through the oil sector, but with 117 people indicted and Petrobras’ plummeting market value, much of that hope was erased. The CEO and four members of the board of directors resigning in addition to the 2,000 employees under investigation only further damages the situation. The Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority recently declared that Petrobras represented a clear case of corruption.

Aside from the notoriety of Operation Car Wash, Petrobras received attention for its series of oil spills. In 2012, a leak in the Santos Basin, a location off the coast of Brazil, extended 43 square miles. Then in 2015, Petrobras shut down four oil platforms after they released 7,000 liters of oil off the northeast coast. Two months later, a spill occurred in Rio de Janeiro’s Costa Verde, a favorite tourist location and one of the last places of endangered Atlantic-Forest ecosystem. This year oil and gas leaks on Petrobras’ floating, production, storage, and offloading unit in the Campos Basin forced the company to terminate production.

Petroblah

The question that Harvard community members must ask is whether Harvard should continue to invest in and thereby endorse this particular value system. It is important to make known the operations of companies that Harvard relies on to grow its portfolio and to evaluate if the negative effects and histories of corporations should be weighted when Harvard makes investment decisions. As peer institutions such as Yale or Stanford begin divesting or partially divesting because of the “risks of climate change,” we must ask why Harvard fails to follow, particularly given the behavior of the fossil fuel and fracking companies the university financially supports through its investments.

Back in 1990, President Derek Bok justified the decision to divest from tobacco companies by explaining that the choice “was motivated by a desire not to be associated as a shareholder with companies engaged in significant sales of products that create a substantial and unjustified risk of harm to other human beings.” I fail to see how fossil fuels skirt such a description.

Divest Harvard is a student group that campaigns for Harvard to draw down its investments in fossil fuels, and Democracy Matters is a student group that studies the influence of money in democracy. This piece is part of a series on Harvard’s fossil fuel investments.