On April 28, 2019, VO2 Vegan Cafe had its biggest day ever. More customers than ever before stopped by for Spicy Monkey smoothies, Seitan Slam sandwiches, and meatless taco salads. There was laughter. There was conversation. There was nutritional yeast.

And then the next day, there was nothing. Forever. VO2 Vegan Cafe milked its last nuts on April 29, joining the flurry of closures that has wracked Harvard Square for the past three years. As long-time standbys have bid adieu, new restaurants and fashion outlets have descended upon the Square, leaving plenty of time for two popular narratives to emerge: first, that the Square’s indie businesses are being squeezed out by big corporations; and second, that affordable options have vacated the Square to make way for pricey tourist traps.

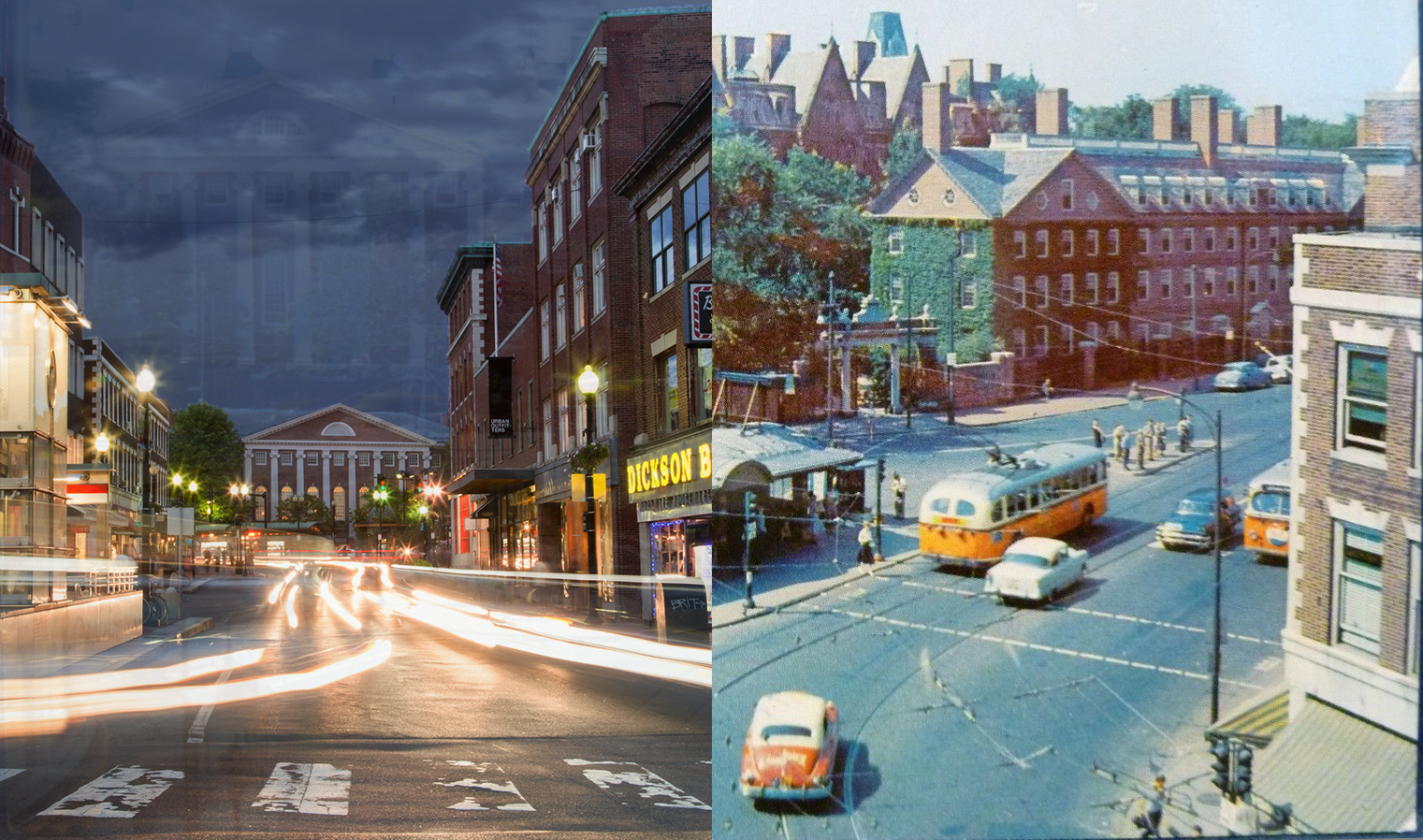

To many who have lived or worked in Harvard Square for a long time, the groans about change seem just as constant as the change itself. But the current evolution of Harvard Square may be more complex, or at least different, from changes of the past. Today’s Harvard Square is changing in the era of online shopping, food delivery, and mobile payment. And many property owners are trying to adapt — in part to keep up with these new trends, for example, landlords may impose rent hikes or plan renovations. A combination of these factors has affected businesses in the Square as diverse as Crema Cafe and Chipotle.

These forces seem to work for consumers by offering convenience, affordability, and greater selection. But they have also undermined the quirky, independent personality that defines Harvard Square. Change is not inherently bad, but recent trends in the Square feel out of control, driven by changes in technology, shifting consumer loyalties, and perceptive property owners. As consumers and residents interested in preserving the cultural architecture of Harvard Square, we may be unable to draw up neighborhood plans, but our collective actions speak volumes. At the very least, we have a responsibility to understand our own role in sculpting Harvard Square.

Price Is Not the Point

Although ownership and affordability have influenced openings and closings in Harvard Square, neither factor has broadly defined the neighborhood’s recent turnover. Many independent businesses have indeed closed their doors since 2017, including Schoenhof’s Foreign Books, John Harvard’s, and Crema Cafe. But the same has been true for chain stores — the past year alone saw closed locations for companies like Chipotle, Au Bon Pain, Urban Outfitters, and Starbucks. In fact, despite fears of corporate takeover, the Square’s business landscape remains roughly 70 percent independently owned or operated, according to Denise Jilson, executive director of the Harvard Square Business Association. That number has remained stable for years, she said in an interview with the HPR.

Similarly, changes in the Square run the gamut of affordability. Since 2017, some more expensive spots like Blue Bottle and the Longfellow Bar have cropped up, but turnover has in some cases increased affordability. For example, a meal at fast-casual West Coast chain Veggie Grill will be generally less expensive than one at 57 JFK Street’s former tenant, Wagamama. Milk Bar and &pizza may not be McDonald’s, but they replaced fine dining destination Tory Row in early 2019. And according to Jilson, the Bluestone Lane coffee shop moving into Crema Cafe’s former location will offer similar cafe options at lower prices. Overall, it appears that affordability cannot explain turnover in the Square.

The “Mallification” of Harvard Square

If there is a common thread to closures in the Square, it is that businesses are being aggressively influenced by entities whose main connection to the neighborhood is financial rather than social. This kind of ownership by third parties is nothing new, but what is different is the way that these properties are being managed. And in many ways, these landlords are merely trying to keep up with changing consumer spending habits.

“You have a very hot and dynamic retail market, and that’s why you see these investment companies coming in,” said Lisa Hemmerle, economic development director for the City of Cambridge, in an interview with the HPR. Recognizing consumer demand for convenience and consistency, some of them are trying to mold Harvard Square to those demands.

When Tealuxe closed in December 2018, news spread quickly that the popular tea shop was yet another victim of big business. In reality, Tealuxe’s building had been slated for renovation by Regency Centers Corporation for years. Closures of three of the building’s tenants — Tealuxe, Sweet Bakery, and Urban Outfitters — were all planned and expected, according to Jilson.

Similarly, Regency Centers Corporation’s plans for renovating the Abbott Building, also known as the Curious George building, will displace the eyeglass store Vision House, as well as the World’s Only Curious George Store itself. Adam Hirsch, the toy store’s owner, announced in early May that he would be relocating to nearby Central Square after closing on June 30, 2019.

Many of these disturbances are a response to a changing vision of consumerism in the Square. Landlords see untapped potential in some of the area’s prime real estate. They believe customers are willing to pay more for a set of modern amenities that their current tenants don’t offer — like an updated food menu, Apple Pay capability, and online ordering infrastructure. In part, rent hikes are the natural response, encouraging tenants to make these changes or risk being replaced.

By 2017, assessed property values in Harvard Square had roughly doubled from 2012 values, and the result for many tenants was a sharp increase in rent prices. This was the case for O2 Yoga and its attached VO2 Vegan Cafe, whose landlord decided to increase rent from $11,000 to $44,000 virtually overnight.

“It’ll have to be the University that buys it,” VO2’s founder Mimi Loureiro said in an interview with the HPR. “Who else could afford to pay that?”

Crema Cafe similarly buckled under a threefold rent increase, according to Cambridge Day. When the cafe’s lease ended in 2018, it was clear that Crema would be unable to negotiate a renewal agreement with their new landlord, Asana Partners. Co-owner Lisa Shirazi said she had no choice but to close.

Flat Patties, another tenant operating under the landlord Asana Partners, has said that rent troubles will likely force it, too, to leave the Square. With a lease expiring at the end of 2019, the burger joint’s co-owner Tom Brush said he would probably close the business rather than try to relocate.

Cambridge Mayor Marc McGovern has told the Boston Globe that he is afraid of the “mallification of Harvard Square,” and rightly so. Regency Centers Corporation Vice President Sam Stiebels has said that renovations would update the buildings’ infrastructure so they could survive “another 100 years,” but his corporation’s simpler directive is to install a “pedestrian shopping center” in Harvard Square.

Dwindling consumer loyalty has also universally plagued the Square’s businesses. Chipotle, which leased a space at Brattle Square owned by Piedmont Office Realty Trust, Inc., closed its doors in January 2019, having been outrivaled by nearby Mexican options like El Jefe’s and Felipe’s. Dwindling consumer loyalty also contributed to the 2019 closures of Au Bon Pain and fashion retailers LF and Free People.

Property owners seeking to “revitalize” Harvard Square are just trying to get people — and their wallets — back into the neighborhood. Shuttered windows and “blighted storefronts,” as Hemmerle put it, are worse for a business district than a corporate chain store, especially in Harvard Square, where business vacancy is significantly higher than the city-wide average. And if consumer choices encourage convenience, proximity, and relatively affordable price points, then maybe a mall is exactly what consumers are calling for, albeit unknowingly. This solves property owners’ concerns, too, if the bottom line priority is, literally, the bottom line.

New Tech and Dwindling Loyalty

In Harvard Square and elsewhere, online commerce has taught consumers to value convenience over nearly all other factors. The digital world has created plenty of new avenues for physical businesses, but some may actually end up harming the businesses that adopt them. When Groupon arrived in Boston, for example, Mimi Loureiro thought it could attract new visitors to her yoga studio. She was right, but only partly; Groupon attracted first-time visitors and shoppers who were looking to redeem a 50 percent coupon for a yoga class rather than monthly members who would return time and again.

“People become shoppers, not customers,” Loureiro said. “The level of loyalty diminishes drastically.”

In fact, we as consumers may have a stronger influence than we realize when it comes to shaping the brick-and-mortar business environment. Online shopping in particular has had an outsized effect on retail across the country. Purchases from Amazon can replace visits to any number of physical stores, including gift shops, bookstores, hardware stores, and even grocery stores. And when consumers shop online, they are less likely to buy on impulse, or socially. Without walking through the neighborhood to a physical destination, one does not pass any other shops, and cannot stop to pick up that notebook for class or postcard for the family, undermining the integrity of the brick-and-mortar business community.

Technology has also often harmed brick-and-mortar businesses in the food industry, especially with the rise of food delivery. When a restaurant adopts a food delivery service, it often must give 20 to 40 percent of its delivery revenue to third-party platforms and their couriers — a disaster for some restaurants, especially since delivery has a way of replacing in-store purchases rather than complementing them. On top of that, delivery discourages splurge spending on extras like cocktails, appetizers, and desserts. But even with these harms, which can add up to a one-third reduction in overall profit margin, delivery is addictive. One retailer described delivery services as “crack cocaine” because it is so easy to rely on them even while profits become so paltry as to ultimately kill the business.

In all areas of commerce, there seems to be a tension — between what consumers say they want and how they actually behave. Mayor McGovern’s dreaded malls, for example, are the antithesis of everything consumers claim they value. In a 2016 customer intercept survey conducted by the Cambridge Community Development Department, residents and visitors overwhelmingly reported that their vision of Harvard Square was defined by two factors: its businesses and its distinctive “atmosphere/look.” Some people specifically mentioned words like “funky,” “personality,” and “unique,” and when asked to choose a single word for their vision of the Square, they wrote things like “lively, “vibrant,” “quaint,” and “diverse.”

But as consumers, we also want speed and convenience. This is the frustration of business owners like Mimi Loureiro. “I don’t think people understand,” Loureiro said. “They want it both ways; they want to have their little mom-and-pop places, but they also want the convenience to go and buy whatever whenever.” That is, people want to be able to walk through quaint business districts without patronizing them. They want the greater options, better deals, and faster delivery offered by merchants and services outside the community. “If people really want a business to stay open, they have to make the decision to go there exclusively, as opposed to whenever they feel like it,” Loureiro said.

Fostering a vibrant brick-and-mortar business district requires a concerted effort between government officials, business owners, and community members. Community action could not have saved VO2 or Crema, but our purchasing power can either help “traditional” businesses get by without catering to the whims of the online world, or — if convenience really is king — it can help cleanse the Square of those businesses who refuse to adapt. Over time, we have the power to unintentionally create an outdoor mall in Harvard Square.

Everyone interested in preserving the quirkiness of Harvard Square would have the greatest impact by appealing to city and state government. But policies that support funky, independent businesses must be founded on community support — even the smallest consumer decision serves as a sort of vote for the kind of neighborhood we want to live in. Walking a couple blocks, whether for a meal, a book, or a pencil pouch, helps keep Harvard Square vibrant. And we could all use the exercise, too.

Image Credit: Wikimedia/ebay // Wikimedia/Massachusetts Office of Travel and Tourism