On June 5, 2017, Montenegro became the 29th nation to join NATO. For the tiny Balkan nation of less than a million people, the hardships overcome in joining the international defense organization cannot be exaggerated. Less than a year earlier, the country reportedly averted a Russian-backed coup targeting the pro-Western government. Moreover, since their entrance into NATO, Russia has warned Montenegro of “negative consequences.” For Russia’s revanchist government, the slow drift of nations under their historical influence towards the West represents a challenge to its perceived prerogatives as a superpower.

When dealing with these neighbors, Russia has adopted a curious policy unlike those of many other major powers. Since the fall of the Soviet Union, Russia has supported new “shadow states” carved from neighboring countries unfriendly to its interests. Instead of replacing an uncooperative regime, Russia partitions the country in the hopes of making it easier to subjugate. The practice is intended to reward foreign governments friendly to the Kremlin and punish those that are not, but as recent history would indicate, it has had varying degrees of effectiveness in different circumstances.

Prisoner of the Caucasus: Georgia’s Flirtation With the West

Attempts by a country to move closer to the European Union has been one common source of Russian interference. Like Montenegro, Georgia at one time had strong hopes for a closer relationship with the West. When then-president Mikheil Saakashvili of Georgia declared in 2004 that “our single ambition today is nothing less than becoming a full member of the European Union,” the Kremlin could have only felt sentiments of ill-will.

For many Caucasus states, flirting with the West means playing a dangerous game. Within four years of his speech to the European Union, Mikheil Saakashvili watched his country nearly collapse in the face of a massive invasion by the Russian Federation. The 2008 Russo-Georgian War, a five-day conflict between the two countries, led the Georgian regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia—with Russian support—to declare independence and break away from the central government.

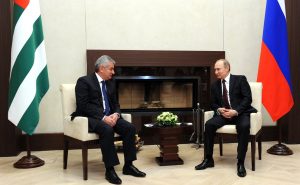

A 2016 meeting between Vladimir Putin and Abkhaz president Raul Khajimba.

Caucasus countries like Georgia and Armenia have expressed a recurrent desire for closer integration with the European Union. Even when faced with pressure to join the Eurasian Union, an economic union led by Russia with aspirations similar to those of the European Union, states like Armenia continue to seek closer ties with the West. Georgia’s war with Russia in 2008 is a powerful reminder of Russia’s continued and pervasive influence in the Caucasus. The complicated political history of these two countries certainly contributed to the tensions which led to the 2008 conflict, but the larger desire to assert authority over a region which appeared to be slipping out of its orbit may have spurred Moscow to act.

Today, Russia continues to recognize Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states, and the “borders” the two entities share with Georgia have gradually begun to creep forward in recent years. Russia has shown no interest in discontinuing its support, and the two Russian-backed shadow states now hugging Georgia’s borders only serve as painful reminders of Moscow’s ambitions.

Georgia lost territory because it challenged Russia’s long history of influence over the tiny country. For other states like Moldova, however, populations drawn to the Russian center of gravity fashioned crises from the onset of independence.

A Russian Nesting Doll: The Republic of Transnistria

Largely hidden from the world, Transnistria is a thin, elongated tract of land between Ukraine and Moldova which maintains a standing military, currency, parliament, and numerous statues of Vladimir Lenin. In keeping with its affinity for all things Soviet, the flag of this unrecognized republic of a half-million people appears nearly identical to the flag of the Soviet Union, with the addition of a green stripe through the middle. This imagery is not accidental: the people of this tiny enclave have maintained recurrent, if elusive, dreams of joining the Russian Federation.

Roadside signs in Tiraspol, Transnistria.

After the fall of the Soviet Union, many troops loyal to the suddenly-defunct empire were caught in the middle of newly-created foreign countries. As part of the newly-formed Republic of Moldova, Transnistria found the prospect of retaining ties to Russia far more tantalizing than becoming Moldovan. With the aid of the Russian 14th Army, Transnistria secured its independence through a successful war with Moldova in 1992. Since then, Russian troops have maintained a presence in the economically-destitute region.

Little seems to have changed in Transnistria since then. Russian troops continue to drill with Transnistrian troops, raising questions about the complete extent of Russian involvement in the region. The Moldovan foreign ministry has protested the alleged recruitment of its citizens into the Russian military. However, without any de facto sovereignty over Transnistria, Moldova’s protests are entirely dependent on the decisions of the Russian government.

However, closer ties between Transnistria and the European Union have also developed in recent years, raising questions of how old political loyalties can accommodate new economic ties. For a country which has recently struggled to maintain economic and political stability in recent years, the presence of the Russian military in Moldovan territory stresses the brittle nature of Moldova’s status as a sovereign state. Although the conflict over Transnistria has largely frozen over, in neighboring Ukraine, Moldovans can get a sense of what happens when Western and Russian interests come to a head.

The Ukrainian Crisis: Different Results in Different Regions

Ukraine’s desire for closer relations with the West, as was the case with Georgia, likely contributed to the civil war currently decimating the country’s east. After Ukraine began making overtures to the European Union, Russia adopted a strategy of interference similar to its method in Georgia: find regions supportive of the Russian government, and aid them in securing independence from an unfriendly state. However, Russia’s success in Ukraine—a country much larger, and perhaps more powerful than Georgia or Moldova—has been more difficult to measure.

Paramilitary forces in Crimea, 2014.

The annexation of the Crimea marked the most blatant example of this approach. Russia’s rapid move to absorb the peninsula in 2014 was much more aggressive than recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia as sovereign states less than half a decade earlier. Most striking of all, Crimea is the only foreign region where Russia has officially declared its sovereignty.

However, there are still other regions in the country whose political status remains undefined. Difficulties in solidifying control over Luhansk and Donetsk in eastern Ukraine—known as the “Donbass” region—represent an obstacle which did not emerge in Transnistria, Georgia, or Crimea. Reports have emerged questioning the mysterious deaths of pro-Russian separatist leaders who led the initial charge for secession. On top of this, conflict operations show no signs of abating, with some Ukrainians now calling for the state to give up hope of taking back the territories. Moscow’s costly foray into eastern Ukraine helped solidify its hold over the Russian-friendly populations in this foreign state, but the resistance from the Ukrainian government exemplifies just how damaging such conflicts can become for all involved parties.

In Russia’s Backyard: What’s Next?

Since 1991, “The Near Abroad” has become a term used to describe the relationship between Russia and the other former Soviet republics now on its borders. The re-emergence of an assertive Russia under Vladimir Putin has increased Moscow’s interest in these regions, and harkens back to Russia’s historical role as the arbiter over the smaller states surrounding it. Working from a weakened position following the end of the Cold War, Putin’s Russia has attempted to maintain influence throughout its periphery by whatever means necessary.

Just as the United States has historically taken a dominant role over the Americas, to what extent is Russia’s influence over ‘The Near Abroad’ natural? While it maintains substantial hard-power advantages, Russia’s current military adventures are unsustainable. With the Russian military budget likely to shrink in the next few years, as the cost of maintaining an empire comparable to the USSR will move from punishing to insurmountable. Russian anxiety about foreign involvement in its neighborhood is nothing new, and should not be expected to disappear in the near future. Involvement in regions as distant as Georgia, Ukraine, and Transnistria have proven feasible in the short term, but have produced little in the way of long-term gains.

With Russia facing demographic and economic crises at home, the viability of these “shadow states” remains wholly uncertain. As extensions of the Russian government located in foreign governments, these entities rightly perplex the outside world with of their ambiguity and invisibility. Only time will tell if they will continue to do so for much longer.

Image credit: Flikr/Dylan C. Roberton // en.kremlin.ru/President of Russia // Flikr/Maxence // Flikr/Sasha Maksymenko