What Is Gerrymandering?

2014 was a tough year for Democrats. In addition to losing their Senate majority in dramatic fashion, the Democrats also saw the Republican margin of control in the House of Representatives grow from 33 seats to 46. They got clobbered in state elections, too, with the GOP securing of 31 out of 50 governorships and an all-time record 68 of the country’s 98 state legislative chambers. In the face of such an overwhelming victory, it seemed clear that the Republicans had won a resounding mandate from the American people.

However, a closer look reveals a much more troubling reality—in recent years, Republican majorities in state legislatures across the country have been using a tactic known as gerrymandering to tilt the political playing field in their favor. Essentially, gerrymandering allows the majority party in any given state to redraw legislative district boundaries so that they are always able to control the most seats, even if they win fewer votes. For example, if the total votes cast in the 2014 U.S. House elections are added together, the Democrats won about 1.4 million more votes than the Republicans, yet the Republicans still won 46 more House seats than the Democrats. State legislative election results are distorted as well. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, in 2014 Republicans won 948 more state legislative seats than Democrats nationwide. Yet in state after state, from Pennsylvania to Michigan to North Carolina, Democratic candidates actually won more total votes than their Republican opponents.

The Democrats are far from blameless, though. From the 1960s to the 1990s, election results were often skewed in their favor, and many of the same disadvantages faced by Democratic candidates today were instead faced Republicans. To this day, states like Illinois and Maryland are heavily gerrymandered to protect the Democratic majorities there. But whether regardless of which party is making use of gerrymandering, the question remains—how does it actually work?

The answer lies in the way congressional and state legislative districts are drawn. In most states, the state legislature is responsible for redistricting. Every ten years, state legislators go back to the drawing board after the results of the U.S. Census are released, redrawing the districts from which legislators are elected. Redistricting is intended to let states adjust to demographic shifts and the reapportionment of congressional districts.

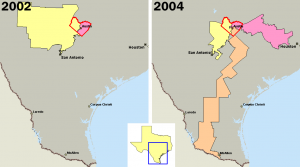

But allowing partisan legislators to redraw their own districts creates a clear conflict of interest, and historically the temptation to game the system has proven too great to resist for the majority party. The Republican Party won a majority in most state legislatures after the 2010 midterms, and they immediately began cramming Democratic voters into as few districts as possible in order to make Republicans competitive in as many districts as possible. Eight of the 10 most-gerrymandered congressional districts in the country were drawn by Republican legislatures, and while the 2014 Republican victory cannot be entirely chalked up to unfair redistricting, political scientists such as Larry J. Sabato and Theodore Arrington have shown that gerrymandering certainly inflated the size of the Republican victory. Gerrymandering turned what otherwise may have been a minor loss for the Democrats into their worst defeat in 74 years.

One side effect of gerrymandering has been the creation of some truly bizarre congressional districts. North Carolina’s 12th district traces the route of I-85, packing hundreds of thousands of black and Hispanic (i.e., Democratic) voters into one district. Florida’s 5th district somehow ties together Jacksonville, Gainesville, and Orlando as it snakes along the St. Johns River, at one point narrowing to a width of barely a hundred feet in order to cross a bridge without diluting the solid republican majorities in the 3rd and 6th districts on either side. Meanwhile, the complexity of Maryland’s 3rd district is simply mindboggling. This might not seem too important, but it’s worth remembering that such oddly shaped districts often divide communities and force numerous local interests to compete against one another – voters from Jacksonville may have significantly different concerns that voters from Orlando, for example.

Coloring Outside the Lines: North Carolina and Michigan

Gerrymandering is an issue endemic to many states, but its effects have been especially dramatic in swing states like Michigan and North Carolina. Although President Obama won North Carolina by only 0.4 percentage points in 2008 and Mitt Romney earned an equally narrow victory there in 2012, North Carolina’s congressional delegation is made up of 10 Republicans and only three Democrats. The lopsided nature of North Carolina’s congressional delegation can be largely attributed to gerrymandering. In fact, on February 5 the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of North Carolina found that in the redrawing of the 1st and 12th congressional districts there was “strong evidence that race was the only non-negotiable criterion and that traditional redistricting principles were subordinated to race.” In fact, the 12th congressional district is the most heavily gerrymandered of all 435 congressional districts nationwide. As a result the North Carolina General Assembly has been ordered to redraw these congressional districts before the 2016 elections, and their request for a stay on this order has been rejected by the Supreme Court.

However, many are unsatisfied with the limited progress that has been made in North Carolina. Bob Hall, the Executive Director of Democracy NC, a Durham-based organization, has said that, in light of the recent court rulings, there may be momentum for a larger overhaul of the redistricting process. Hall also says Democracy NC has looked at possible ways to create a nonpartisan redistricting commission like those in California and Iowa. State Representative Jeff Jackson (D-Mecklenburg) has championed the cause of independent redistricting in North Carolina. He told the HPR there is only one challenge that would face an attempt at redistricting reform in the state: “the threat that an honest redistricting process would pose to the artificial supermajority that currently governs the state. There are no legal objections. There are no unsolvable logistical concerns, in terms of how to implement (reforms). The only remaining hurdle is moral timidity.”

But gerrymandering’s influence is certainly not confined to congressional redistricting. Michigan is a prime example of the distortionary effect gerrymandering can have on state legislative districts as well. According to recent Gallup polls, Michigan is a “purple” state, with 43 percent of Michiganders identify as Democrats or Democratic-leaning independents, while 39 percent are Republicans or lean-Republicans, with about one in five Michigan voters not leaning strongly towards either party. Yet in the 2014 state legislative elections, although Democrats won 51 percent of the total votes to the Republicans’ 49 percent, Republicans won 63 of 110 state House seats and a supermajority in the state Senate. In other words, Republicans won 61 percent of the seats in the Michigan State Legislature despite winning only 49 percent of the votes.

Gerrymandering is further evidenced by the fact that only 21 of Michigan’s 148 legislative seats have been truly competitive (won by 5 or fewer points) since Republican-led redistricting took effect in 2012. Grand Rapids’ state house districts show clear signs of partisan gerrymandering—urban Democratic voters are packed into the 75th district in the city center, while the Republican votes in the suburbs are concentrated in the 76th district, which wraps around the city like a “crescent moon,” as one state official described it.

State Representative Jon Hoadley (D-Kalamazoo), a member of the House Elections Committee, pointed out in an interview with the HPR that “there is not a single congressional district in Michigan that is represented by a Democrat where that Democrat won in 2014 by less than 60 percent,” an assertion supported by election results. In light of all the evidence, Hoadley said that “it’s obvious that a conscious choice was made to optimize the protection of incumbents and the (Republican) majority” by packing Democratic voters into as few districts as possible.

“I live in ground zero of gerrymandering in Michigan,” State Rep. Jeremy Moss (D-Southfield), an Oakland County native, told the HPR. “You don’t even need to know that much about Michigan or about Oakland County to look at a map and wonder: ‘Why are three districts in Oakland County literally spiraling around one another?’ ‘Why do neighboring towns called Bloomfield Hills, Bloomfield Township, and West Bloomfield all reside in different congressional districts?’” Moss said.

Moss pointed out that “communities of interest”—such as school districts, municipalities, neighborhoods, and state legislative districts—should be within the same congressional district, rather than being divided by district boundaries. “For example, Farmington and Farmington Hills are neighboring cities (in Oakland County) which share a school district, community groups, a state representative, and a state senator,” Moss said. “But they don’t share a member of Congress.”

Redrawing America, One State at a Time

North Carolina and Michigan are some of the clearest examples, but partisan gerrymandering has affected nearly every state in the country. In fact, in addition to North Carolina, the Florida State Supreme Court recently ruled that gerrymandered congressional districts must be redrawn in the Sunshine State, while the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld a gerrymandering lawsuit in Maryland and agreed to hear a gerrymandering case from Virginia.

Gerrymandering is an issue which ails liberal and conservative states alike. In order to break this historically entrenched practice, mathematical algorithms may be an effective prescription for taking the passions of partisanship out of the equation. Brian Olson, a Massachusetts software engineer, recently designed an algorithm which uses 2010 Census data to draw districts that are as compact as possible. It does this by respecting the boundaries of “census blocks,” which are the smallest geographical units used by the U.S. government.

If implemented on a large scale, algorithm could eliminate gerrymandering and maximize the geographic cohesiveness of districts, but some say this cohesiveness comes at the expense of preserving communities of interest. While the concept of communities of interest can be very arbitrary, the Voting Rights Act mandates that some majority-minority districts be created within certain states to ensure adequate minority representation in Congress. In practice, however, the effects of this mandate have been mixed, as there is evidence that gerrymandering has often been used to pack minorities into only a few uncompetitive districts in order to dilute their overall voting power.

Some states like California and Arizona have instead opted to form independent redistricting commissions to redraw districts in an unbiased manner. The members of California’s commission include three Democrats, three Republicans, and two Independents who apply through a series of essays and interviews. Lobbyists, employees of political parties, elected officials and their immediate family members, and major donors are not allowed to apply. After the applicant field is whittled down, the state auditor randomly picks half of the commission members from amongthis smaller pool. The selected individuals then convene and select the remaining members. This commission tries to “group together people with shared economic and social features, such as race, religion, sexuality, commuting habits, and household income.” The only factors that the commission cannot use are home addresses or political affiliation. Bipartisan redistricting has made California elections much more competitive: from 2002 to 2010 only one California congressional district switched parties, but after 2012 26 percent of the California’s U.S. Representatives were newly elected to Congress.

Redistricting reform has gained considerable momentum in the wake of the 2015 Supreme Court’s ruling that independent and bipartisan redistricting commissions are constitutional. Legislators and voters in Illinois, South Dakota, Maryland, Colorado, and Ohio may have a chance to approve major redistricting reforms in 2016. Rep. Hoadley and Rep. Moss, the Michigan state legislators, have worked together to propose a bipartisan redistricting commission in Michigan, but have met strong opposition from the Republican leadership of the Michigan House of Representatives; many legislators in other states have met similar obstacles.

Gerrymandering is a pivotal nationwide problem which has left its mark on every state and every political issue. However, the state-by-state nature of the redistricting process means that it must ultimately fall to the states to collectively serve as “laboratories of democracy” in the coming years, discovering the most efficient and effective means of addressing the nationwide need to bring an end to the abuses of gerrymandering, and create a fairer and less polarized America in the process.

Image Credits: United States Department of the Interior/Wikimedia, Henry/Wikimedia