Harvard’s Undergraduate Council Finance Committee is a major source of financial support for hundreds of student organizations, doling out nearly $150,000 of student term bill each semester to support campus life. But who is all that money really going to? And how is it spent? This investigation by the Harvard Open Data Project attempts to answer these questions. Certain types of student groups receive more money than others, and a few student groups receive the most money. The UC’s flawed accountability system also leaves substantial room for improvements to the grants system.

Data Collection Methods

The earliest accessible data came from the UC archives from the fall of 2015. This data was riddled with errors as the UC had used poorly-constructed excel spreadsheets to manage the entire grant process. Beginning in the fall of 2016, however, the UC began to standardize names in its sheets and use more sophisticated conditional logic to validate its data. In the spring of 2017, the UC unveiled a web app called Nova to conduct its business, fully automating data input and validation. In addition, all Nova data has been made available to the public. Thus, we are confident in the accuracy and validity of our data starting from the fall of 2016, but less confident in data prior to that date.

What Kinds of Groups Get the Most UC Money?

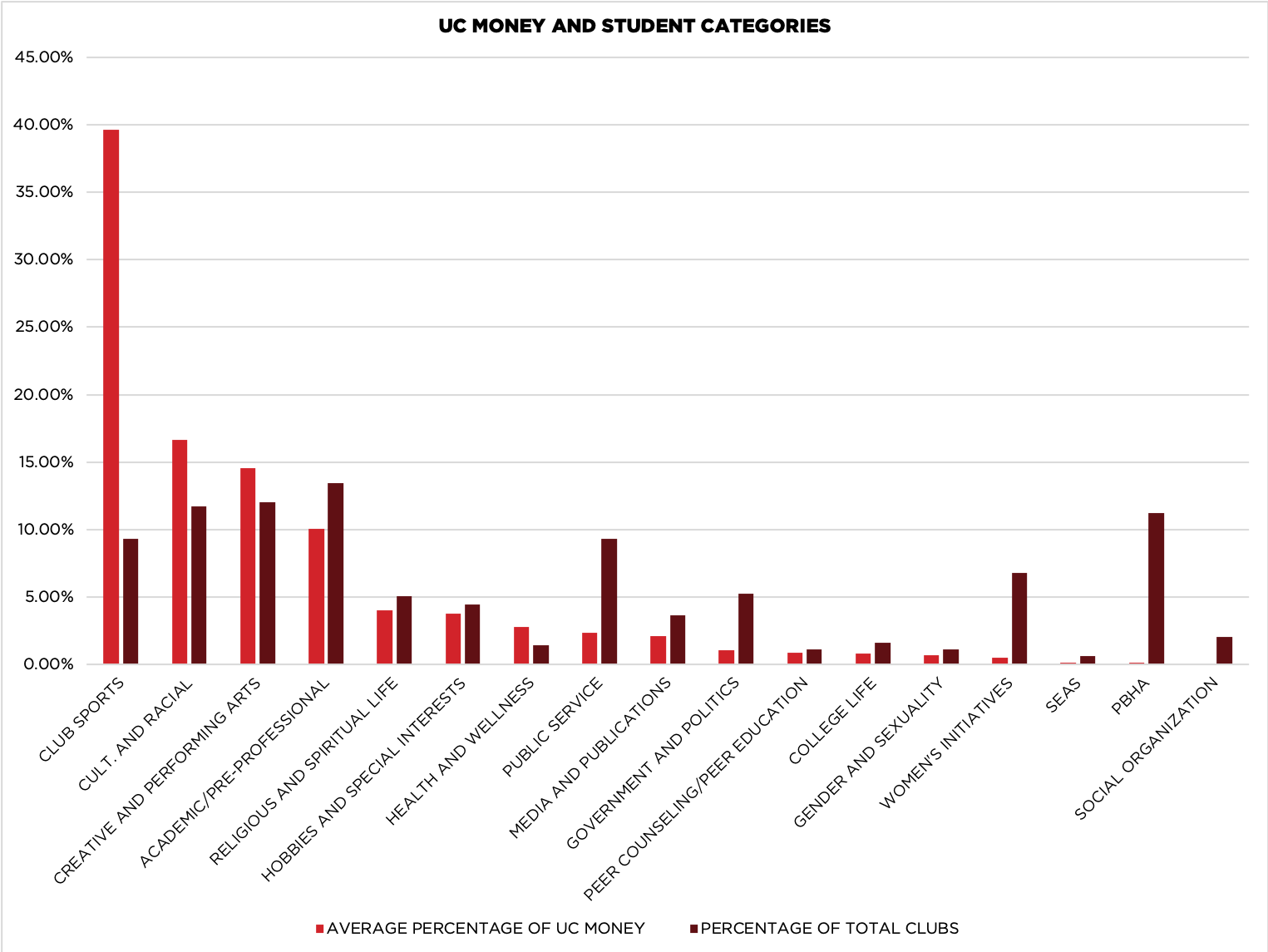

Every student group eligible to apply for UC grants is sorted by the Dean of Students Office into one of 15 categories based on their primary purpose, such as Public Service or Cultural & Racial Initiatives. We compared the average percentage of total funding that each category received from the UC and the proportion of representation of each category on campus over the past two years.

We found that the largest portion of UC money — 39.64 percent of the semester total on average — goes to Club Sports even though the category only accounts for 9.32 percent of DSO-recognized clubs. Club Sports are followed by Cultural and Racial Initiatives (16.64 percent of UC money and 11.69 percent of DSO-recognized clubs), Creative and Performing Arts (14.57 percent and 12.01 percent), and Academic and Pre-professional (10.06 percent and 13.43 percent). Categories that have received notably less money than one might expect given their representation on campus include Public Service, (2.31 percent and 9.32 percent) Government and Politics (1.03 percent and 5.21 percent), and Women’s Initiatives (0.68 percent and 6.79 percent).

On an important note, the more than 80 clubs under the Philips Brooks House Association — a student-run, nonprofit public service organization at Harvard College — is a slightly special case, as their programming receives a large grant from the UC separate from the Finance Committee. Therefore, the difference between the average amount of Finance committee money PBHA clubs have received and the representation of PBHA clubs on campus is less concerning.

Differences in levels of funding may be attributed to a number of different factors, such as variation in sources of outside funding, operating costs, and sizes of groups across categories. The disparities could also be attributed to UC policies that favor certain categories of groups over others, like the Finance Committee’s Club Sports week — a special week in the semester dedicated to club sports when the UC usually allocates one-third of its semester budget. The next UC administration should investigate and explain these discrepancies in the interest of transparency and fairness.

Who Is Getting the Big Bucks?

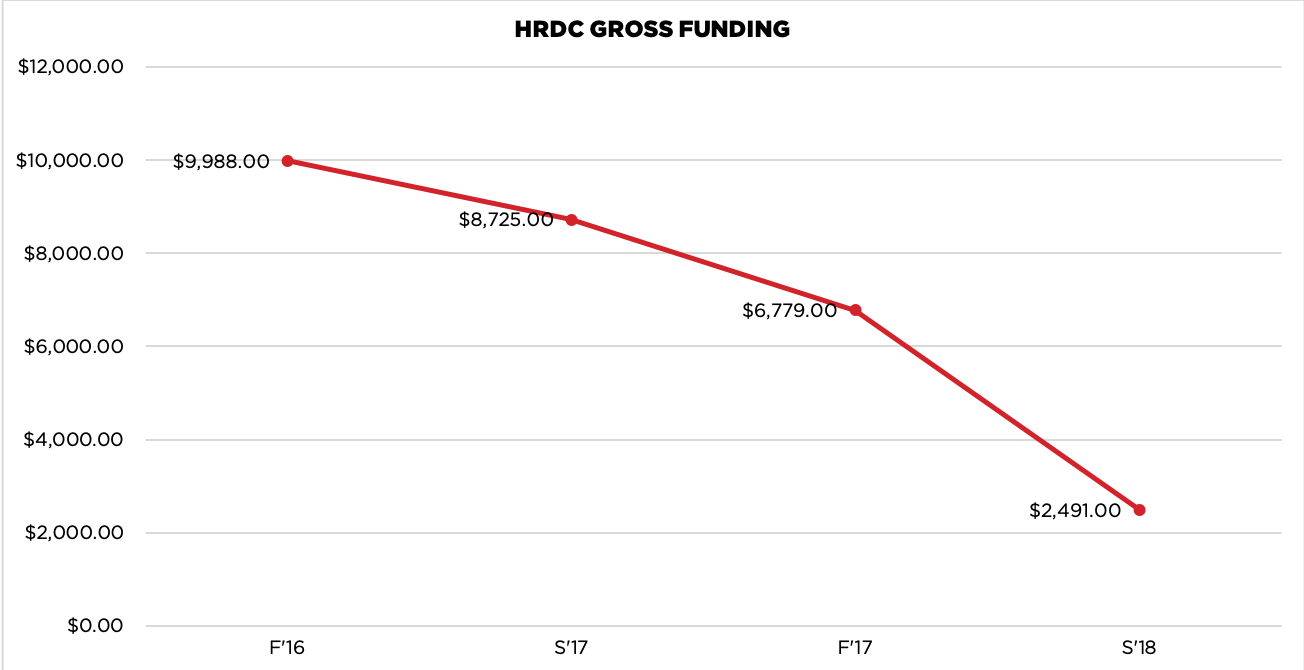

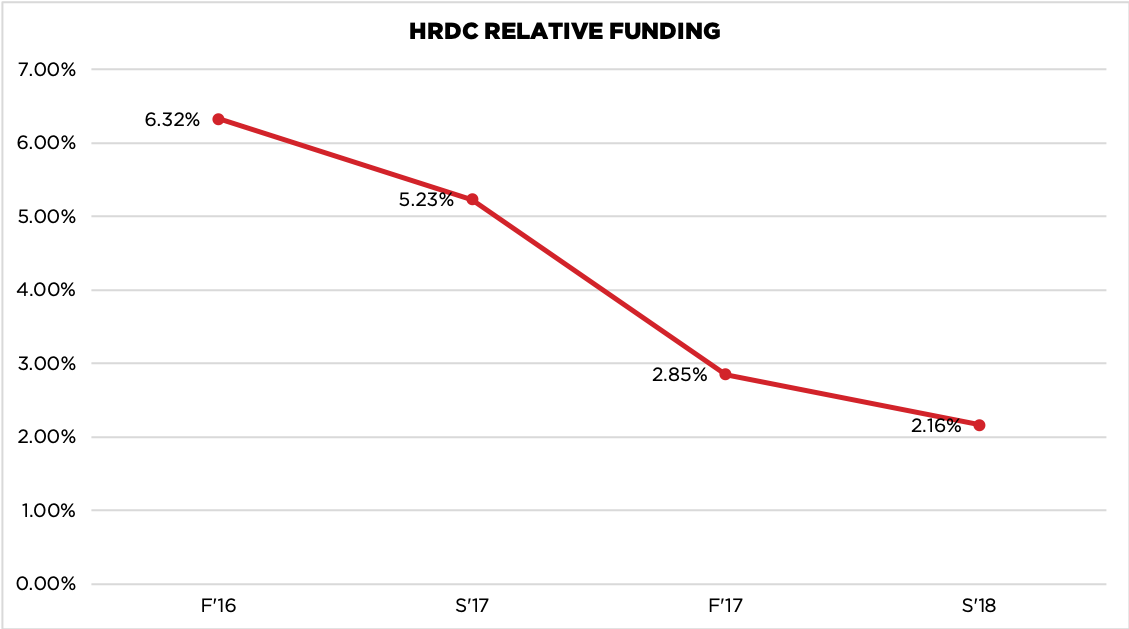

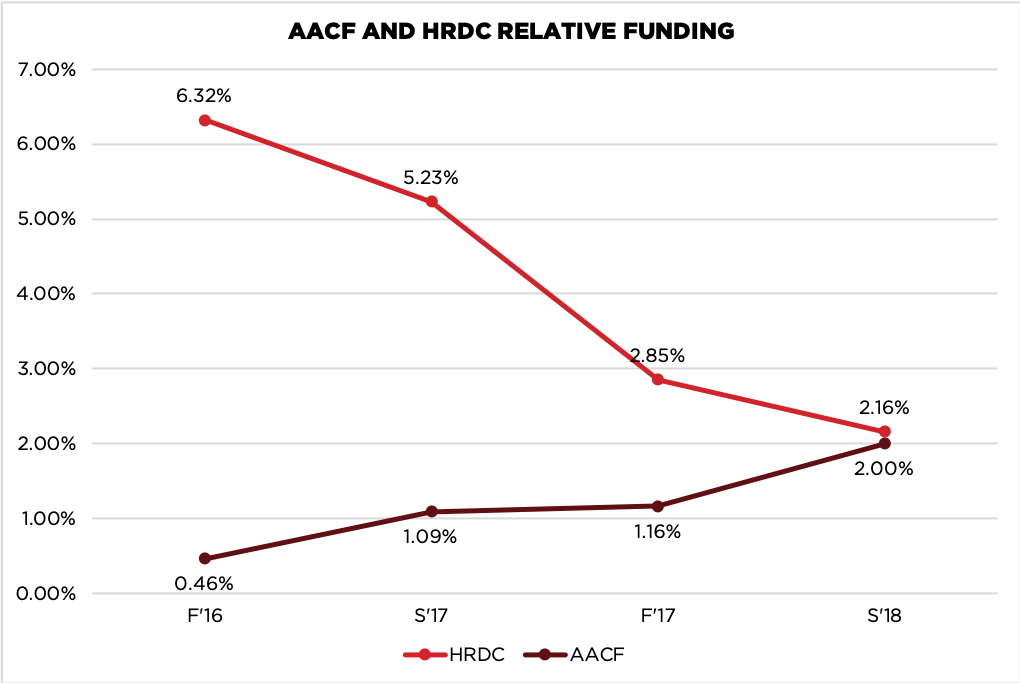

The Harvard-Radcliffe Dramatic Club has consistently received massive amounts of funding in order to finance its many performances throughout the school year, receiving the most funding out of any club in every semester but one. However, the amount of UC funding for HRDC has steadily declined since the fall of 2016. Even a small drop between semesters amounted to a rather steep decrease from $6,779 to $2,491.

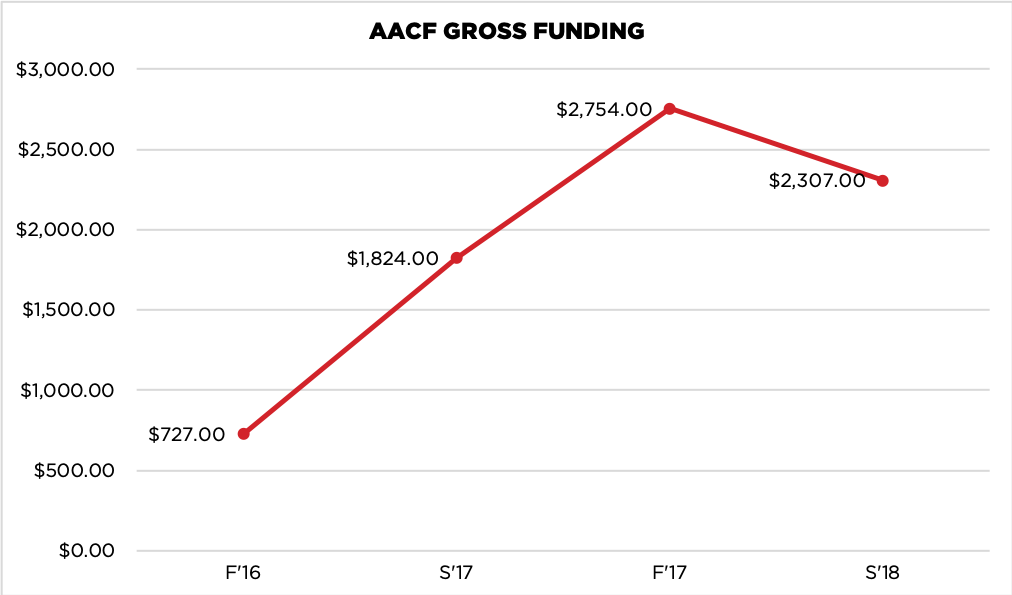

Meanwhile, the Asian American Christian Fellowship has experienced impressive growth in funding over the past few semesters, rising from only $700 in the fall of 2016 to over $2000 in the spring of 2018 and boosting its ranking as the 74th most-funded club to one of the top five. The reasons behind the AACF’s funding windfalls are unclear. The group might have just asked for more money, or it may have bolstered its grant application with more compelling detail on its funding needs and where the money will be spent.

In fact, the AACF’s share of the total funding provided by the UC has risen to the point of approaching the HRDC.

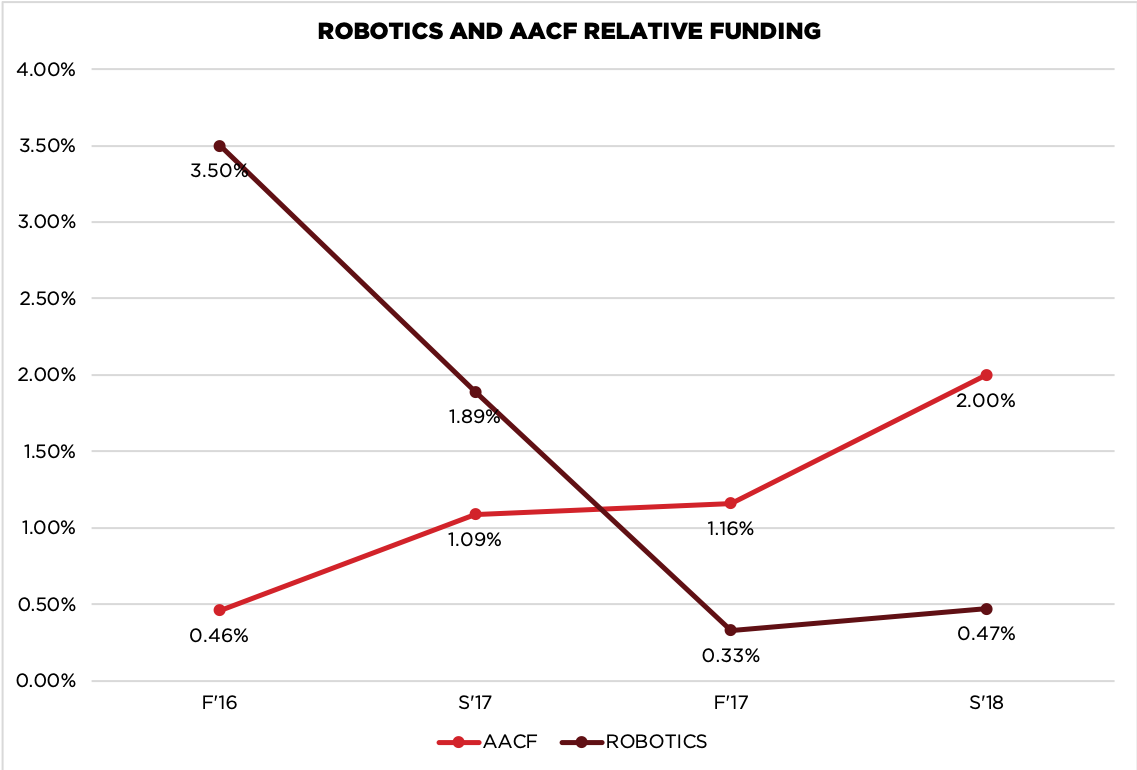

In contrast, another large club, the Harvard Robotics, has drastically reduced its reliance on UC funding over the past few semesters.

This shift away from UC funding is presumably due to the growth in the group’s independent funding. Most clubs that request funding from the UC do not have a steady source of income, yet recently, Robotics has obtained many sponsors. The club’s website shows that it has one platinum-level sponsor, denoting a contribution of over $10,000, and two gold-level sponsors with contributions exceeding $5,000, among others.

What Is UC Money Being Spent On?

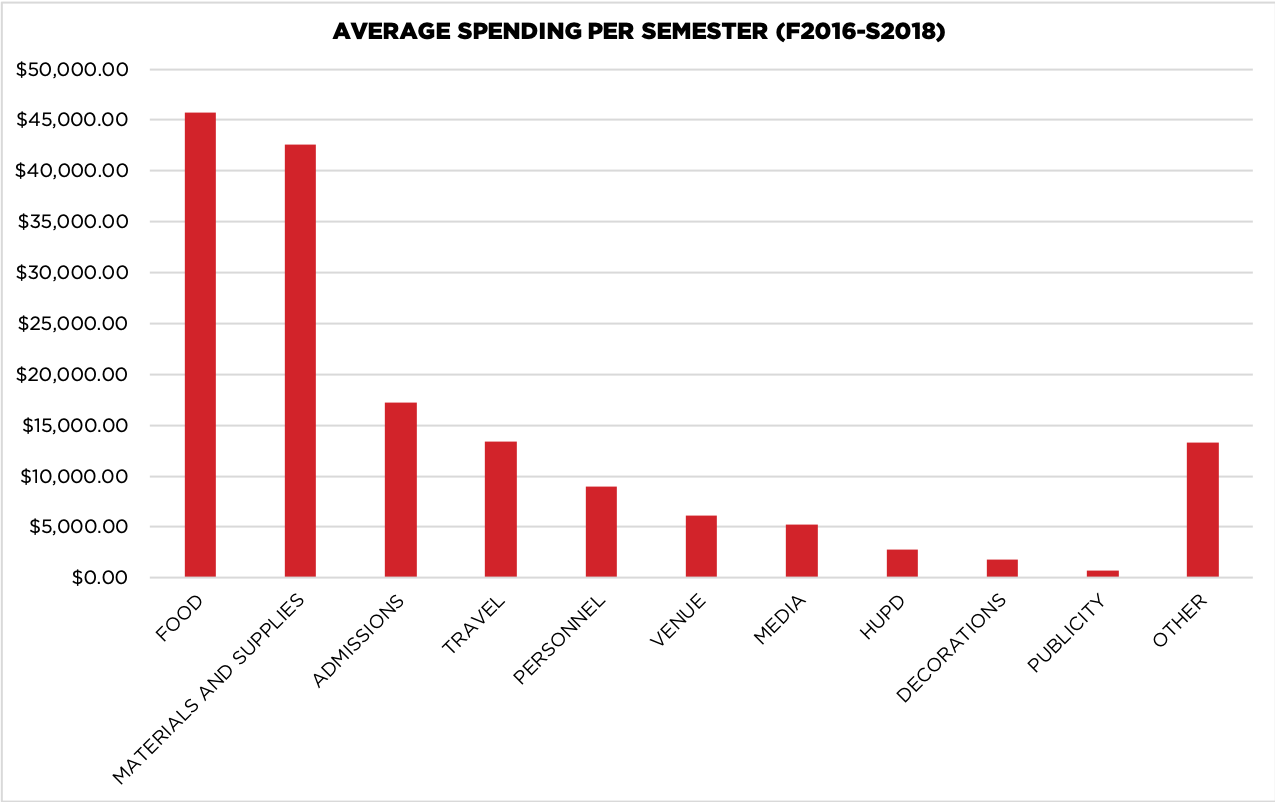

The types of things that UC grant money is spent on is also publicly available information. According to the UC Policy Guide, grant money is allocated to one of 11 expenditure types.

Since the fall of 2016, the two largest areas of expenditures are “Food” and “Materials and Supplies,” with the plurality of UC money funding food for student groups. By subsidizing food for open club events and group meetings, the UC has spurred social life on campus through the social and interpersonal aspects of student organizations. The UC deserves praise for encouraging student groups to host these kinds of community-building activities.

The rationale behind such a large amount of funding for materials and supplies, however, is less clear. Per the UC policy guide, funding for materials and supplies is allocated entirely at “the discretion of the committee.” Though the committee does state that they prioritize “items that are absolutely essential and reusable,” the parameters of “Materials and Supplies” are otherwise ambiguous. Rather, the category functions as a catch-all category for everything from club websites to tennis balls to theatrical backdrops, with individual grant amounts ranging from a couple dollars to a couple thousand dollars.

Unlike many other categories of expenditures, like food and travel, that have measurable factors for determining grant amounts — like the number of people in a club or the distance travelled for events — there is no easy way to estimate the amount of funding a club should receive for materials and supplies. Furthermore, this subjective and discretionary system opens the door for inconsistency as similar items could be treated differently.

To fix this shortcoming, the UC should create categories for items that frequently qualify as materials and supplies with clear and objective criteria for classifying them to ensure that similar items receive similar treatment. This reform should decrease the number of instances where grant money is determined via committee discretion. As for items that still do not fit into any of the categories and thus require the use of discretion, the UC should elaborate on its system of prioritizing.

Accountability

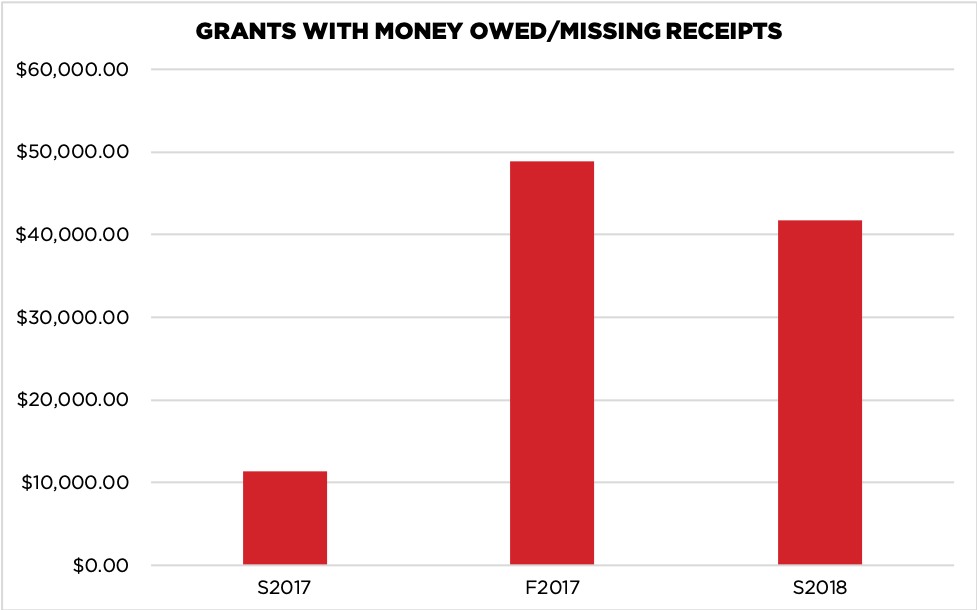

Per the UC Policy guide, all student groups that receive Finance Committee grant money must submit receipts to verify their purchases. Groups are also obligated to return any unspent funds to the UC. However, Nova data shows that enforcement of these policies has been troublingly lax. In fact, since the spring of 2017, over $100,000 in UC grant money has been spent improperly, meaning groups have either failed to return unspent funds or failed to submit valid receipts.

Lax enforcement of these policies enables groups to manipulate the system to spend grant money on projects that have nothing to do with their original application. Furthermore, up to this point there has been little to no real penalty for groups that failed to meet these basic standards for accountability.

The blame for this lack of accountability lies with both the UC and student clubs. The UC should be doing a better job of ensuring that student groups submit receipts and return unspent money, enforcing their own policy guide, and imposing penalties on clubs that fail to comply. On the other hand, student groups must recognize that UC grant money is coming from student term bills; these groups have an obligation to spend responsibly out of respect for the student body.

Room for Improvement

Hundreds of small, student-run clubs and organizations on campus rely on UC grant money to function. It is important that the process of allocating this money is as transparent as possible and regularly evaluated so that all groups are fairly and equitably treated. This investigation has attempted to demystify UC grants and identify strengths and weaknesses in the current system. We call upon the UC to use the report as a starting point to conduct a thorough reevaluation of their grant system, heeding our recommendations in order to ensure that student money is being spent effectively, fairly, and responsibly.

This article is the product of analysis by the Harvard Open Data Project, a student-faculty group that analyzes public Harvard data to hold Harvard institutions accountable.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons/Bostonian13