This article was co-written by Jelena Dragicevic and Brammy Rajakumar.

In his farewell address to the American people, President George Washington proclaimed in 1796, “Citizens by birth or choice, of a common country, that country has a right to concentrate your affections. The name of American, which belongs to you, in your national capacity, must always exalt the just pride of Patriotism, more than any appellation derived from local discriminations.” Although Washington was trying to instill the idea of nationhood into a still-forming nation of thirteen disparate colonies, his words set a precedent for contested notions of “Americanism” and “patriotism.” As data from the Spring 2020 Harvard Public Opinion Project poll shows, young people across the nation approach these two terms with varying definitions and levels of support. This variation, informed by a long history of racism and xenophobia, reveals that there is a major disconnect in whether or not members do feel as equal “citizens … of a common country.”

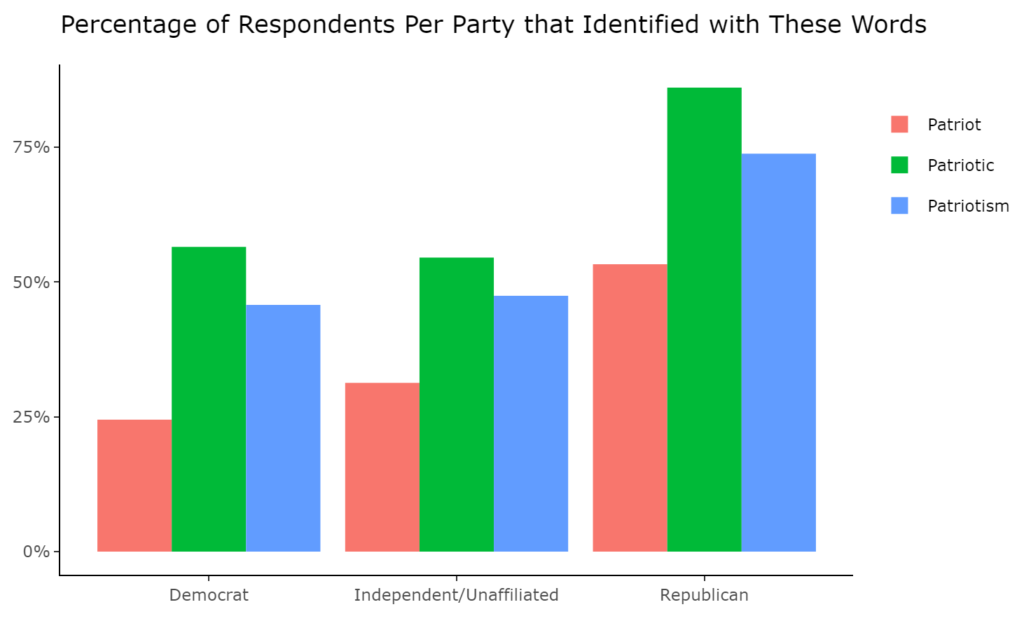

Support for patriotism has declined broadly over young Americans across the past two decades. According to the HPOP poll, the proportion of young Americans ages 18-29 identifying themselves as patriotic has decreased by nearly 30 percentage points, falling from 89% in 2002 to 61% in the present day. In fact, more young people have even expressed outright aversion to the label — the number of young Americans who identified as “not at all patriotic” spiked up 10 points from nearly zero at the start of the millennium to 12% in 2020. These trends reflect the shifting views of younger Americans compared to their peers from past decades and speak to a decline in their identification as “patriotic.”

However, even among the young generation studied, self-assessed levels of patriotism vary across political parties. Young Republicans are significantly more likely to identify as patriotic than young Democrats, with 86% of young Republicans identifying as patriotic compared to 56% of young Democrats. Of the young Republican respondents, 41% call themselves “very patriotic,” compared to only 11% among young Democrats. This data suggests that the Republican and Democratic parties differ in both the quantity and potency of patriotism among their supporters.

Underlying these partisan differences is a historical shift that has made the Democratic Party increasingly left-wing and the Republican Party right-wing over the course of the past century. Prior to the 1930s, Democrats who were predominantly concentrated in the South and southeast U.S. held hardline beliefs against Black Americans and fiercely defended states’ rights with limited centralized authority. Gradually, northern Democrats steered away from Southern Democrats’ alienation of Black Americans, initiating the realignment of Black voters in the 1920s (especially as the Republican Party continued to dismiss civil rights).

The Great Depression and President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s tenure during the 1930s provided the impetus for the Republican and Democratic parties to switch, with the Democratic Party’s New Deal offering social welfare policies that sought to address the failing economy that disproportionately affected Black Americans, as well as other ethnic and racial minorities. While FDR remained reserved about his opinions on civil rights, his administration set the tone for minority groups to primarily identify with the Democratic Party. Accordingly, only 8% of all Blacks, 28% of all Hispanics, and 12% of Asians in the U.S. identify as Republicans, compared to 84% of all Blacks, 63% of all Hispanics, and 65% of all Asians identifying as Democrats today.

Coupling the status quo with the low support for “patriotism” among young Democrat respondents aligns with the anti-minority connotation that the term itself is often wrapped up in. As the scholars Jim Sidanius and Felicia Pratto explain, “American patriotism has always been racialized.” Sidanius and Pratto continue that “nationality and ethnicity are complementary because their power has enabled whites to successfully define the prototypical American in their own image.” Further corroborating this notion that “American” equals “white” and thereby “white” equals “patriotic” is the work of researchers Thierry Devos of San Diego State University and Mahzarin R. Banaji of Harvard University, who found these connections to be implicit and rooted within our unconscious mind. Therefore, while “patriotism” intuitively means “loyalty to one’s country,” it is white Americans who have been propagated as being inherently “patriotic.”

President Trump’s own rhetoric harkens back to this definition of patriotism. The phrase “America First,” which he mentioned in his inaugural address, builds on a history of xenophobia, immigration issues, and ultimately, racism. In 2019, President Trump also criticized four minority congresswomen, three of whom were born in the United States, by telling them to “go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came” instead of advocating for reform in America’s political system. Even in 2020, Trump continues to make race a key part of his strategy, which some have labeled an exclusive “white identity politics” that alienates people of color. Despite this exclusivity, in his inaugural speech, Trump did note that “whether we are black or brown or white, we all bleed the same red blood of patriots,” implying a definition of patriotism that transcends race differences, although young people of color might not have cause to feel this way.

This paradoxical construct of “patriotism” — both universal and exclusive — has largely been informed by clashing perspectives of different racial and ethnic groups, shaped by their complex and often competing histories. If one dissents against institutionalized, discriminatory, prejudiced practices, as did San Francisco’s 49ers former quarterback Colin Kaepernick by kneeling during the national anthem, it is perceived as “unpatriotic” by non-minorities who are convinced that such behavior stands in opposition to America’s democratic values. To minorities, the act is not symbolic of disdain for democracy, rather a commitment to improving democracy. Essentially, minority groups believe in the democratic cornerstone of equal protections for all, and they are willing to exercise their freedom of expression to communicate when these ideals of democracy are jeopardized. Non-minorities perceive minority dissent as a defiance against democracy and thereby “unpatriotic” because they lack the same oppressed history as minorities do to attach minority-dissent to a broader social and historical context.

Data from HPOP, alongside other national data and research, gives credence to the overall schism in the definition of “patriotism” among young Republicans and Democrats, which is primarily a result of the Democrat’s more diverse constituency compared to Republicans. Despite young Democrats identifying themselves as “patriotic” less frequently than young Republicans, this statistic is not per se a depiction of young Democrats’ lack of “loyalty” and unwillingness to prioritize the best interests of the United States. Consequently, HPOP provides a glimpse of contested versions of “patriotism,” revealing divided attitudes towards what it means to be “American.”

Image Credit: Flickr/David M. Curtis