Young Americans want the United States to employ a less interventionist strategy on the international stage, according to the spring 2014 results from the Harvard Public Opinion Project. On all questions relating to debates about current foreign policy topics, respondents overwhelmingly expressed disillusionment with the Obama administration’s actions: 62 percent said that they disapproved of the president’s handling of the Syria crisis, while the government’s policies towards Iran and Ukraine were both met with 59 percent disapproval.

In answers to more general questions, respondents also expressed a more muted international posture: 74 percent of respondents agreed with the statement, “The United States should let other countries and the United Nations take the lead in solving international crises and conflicts,” whereas only a quarter believed that the United States “should take the lead in solving international crises and conflicts.” Similarly, the percentage of young Americans who agreed that “it is sometimes necessary to attack potentially hostile countries, rather than waiting until we are attacked to respond” was only 16 percent—less than half of those who disagreed with the statement (39 percent) and marking an eight-point drop from the previous year’s survey results.

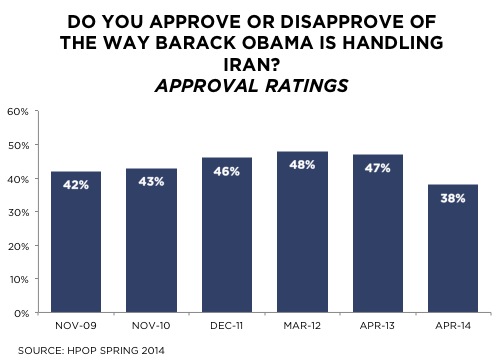

Therefore, overall support for the Obama administration’s foreign policy efforts appears halfhearted at best. Even more significantly, though, support for an active United States has decreased over the past year. In 2012, for instance, almost half of all young Americans approved of the president’s policy in Iran (see chart). By spring 2013, this approval had slightly decreased to 47 percent. Just one year later, that figure has sharply declined to 38 percent. A similar trend was observable on the question of whether the United States should attack potentially hostile countries: the percentage of respondents who agreed also dropped nine points.

This trend of disillusionment is consistent with a broader distrust in federal-level institutions. Although the post-2010 period saw fairly consistent levels of trust in both the presidency and the military, this year saw a seven-percent drop in young Americans’ faith in both of these institutions. Trust in Congress has also decreased by nine percent over the past two years.

In many ways, the current disillusionment with American foreign policy is self-explanatory. The past year has seen a series of international crises in areas such as Syria, Mali, Egypt, and Ukraine, and the U.S. response in many of these cases has sought mainly to avoid raising tensions even higher. In those cases where President Obama did seem to take a decisive role—the famous “red line” comment regarding Syria is an example—American efforts seemed to backfire, resulting in messy diplomatic quandaries and potentially threatening America’s international credibility. There is no Osama bin Laden to kill this year to boost approval—instead, drone strikes are becoming increasingly controversial in the United States and throughout the world.

But while young Americans would rather have the United States stay out of international conflicts, they still are hesitant to trust international institutions. Only about a third of respondents expressed that they trusted the United Nations all or most of the time, while two-thirds said they trusted the UN only some of the time or never at all. Admittedly, skepticism about the United Nations has not risen as rapidly as distrust in many American political institutions; on the contrary, it has been increasing fairly steadily at an average rate of 2.25 percent for the past five years. This figure instead points to a less volatile but more persistent form of disillusionment with international institutions.

While not apparently connected to the drastic increase in disillusionment with President Obama’s performance, this low confidence in the international community hinders attempts at crafting foreign policy initiatives that solve international problems while satisfying young Americans. Thus, policymakers face a quandary: if a conflict occurs internationally, to whom do young Americans turn? Who should intervene to end the Syria crisis, for instance? Is there even a role for international resolutions of violent conflicts?

Kate Donahue contributed to the reporting of this article.