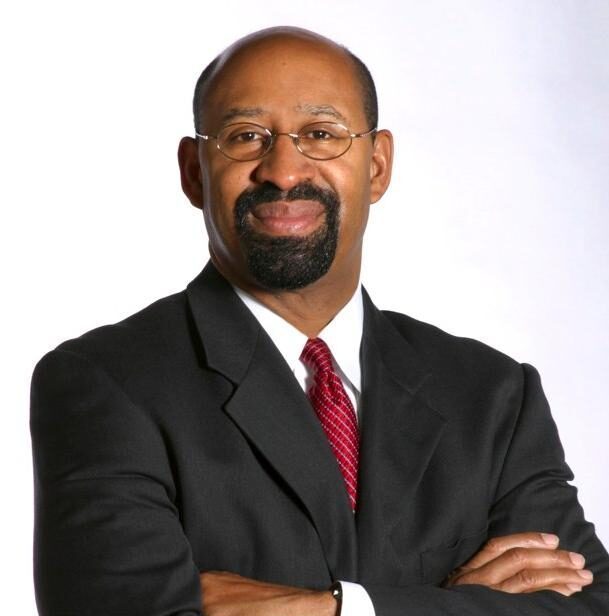

Michael Nutter is a 2020 Fellow at the Harvard Institute of Politics and served as the 98th Mayor of the City of Philadelphia. Mayor Nutter guided Philadelphia through the Great Recession and, under his leadership, the city’s credit rating was upgraded to an “A” by the three major credit agencies for the first time since the 1970s. He is the past president of the United States Conference of Mayors and a frequent CNN political commentator.

Harvard Political Review: As mayor, you led the city of Philadelphia through the Great Recession. Can you speak on your strategy towards bettering your community in a time of major crisis?

Michael Nutter: I think you need to have some fundamental principles of how you’re going to govern. We of course did not anticipate the Great Recession, which was the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. Obviously, current times may show that the pandemic-induced recession is even worse, but the Great Recession was a very difficult period for Philadelphia and all cities across the country. But I had campaigned on the principle of fiscal integrity. I had lived through a different financial crisis that the city faced in the early 1990s. I saw and witnessed many of the strategies of the mayor and administration at that time and certainly used some of that experience.

But we were also committed to making sure that we had the financial resources to be able to run the city. And so we were strategic in our cuts, which we had to make to reduce our costs, and we also had to generate new revenues. We ended up balancing our budget, about 50% new taxes and 50% cost reduction cuts. We stayed in constant contact with the rating agencies about what we were doing and why. We were very public in our announcements about what we were doing and why. And I constantly talked about the need for fiscal integrity, transparency, and a commitment to running the city in a responsible financial matter.

We take an oath to protect the taxpayers and their hard-earned dollars. And I took that oath very seriously. I think many of the things we did worked, but some of them didn’t. Overall, though, when the recession ended, we were rewarded by being one of the few cities in America that saw their bond rating or credit rating go up in the aftermath of the recession.

HPR: When it comes to policy, how do you advocate for your values while simultaneously recognizing that sometimes progress necessitates compromise?

MN: I’m very clear on what my fundamental principles are. I have a saying that you can negotiate the concept, but you don’t negotiate on your principles. You have to very quickly determine what your fundamental bottom line is. Where will you not go? What is unacceptable? Once you’re clear about those issues, then you have to decide how important it is to get something done. How badly do you want it? What’s the goal? What’s the purpose?

We structured our government at the time around four fundamental principles. We wanted a safer city — that’s a focus on public safety and reducing crime and violence. We wanted a smarter city — that’s about helping young people get through high school, college, or some other higher learning program. The third principle was our focus on economic opportunity and a more sustainable city. We had to grow the job base, grow the population base, and broaden our tax base. And the fourth principle was that we would govern with integrity and transparency. And so every decision that we made was looked at through the screen of those four fundamental principles.

Some people think any deal is a good deal. Well, that’s just not true. A good deal is one where you get some of the things you want, and the other person probably gets some of the things that they want. More than likely, neither side is tremendously thrilled and happy. But often, those are some of the best deals that you can make.

HPR: Not only did you serve as mayor, but you also served as the David N. Dinkins Professor of Professional Practice in Urban and Public Affairs at Columbia University. What do you believe to be the key similarities between the mission of an educator and a politician? Are there any key differences?

MN: I think there are a lot of similarities. When you’re in elected office, you should spend a lot of time helping to educate the public. Why are you here in the first place? Again, what are your goals? What’s your plan? What’s your vision for the future? You have to be a good communicator and share that knowledge and information. You cannot assume that everyone is sitting around waiting with bated breath on every word that comes out of your mouth.

In reality, citizens do not spend anywhere near as much time thinking about elected officials as any of us would like to think. They have real lives and often are not glued to the TV, newspapers, or social media. You have to communicate on a variety of platforms on a regular basis. I often say to be concise, be consistent in your communications, and really let people know why you are doing whatever it is that you’re doing.

Constant communication is critical to helping folks better understand what it is that you’re trying to accomplish. I carry that same mindset into the classroom, or when we used to be in the classroom. The same thing applies when I speak to students at Harvard, whether it’s on campus or on Zoom. It is critically important that elected officials not assume that everyone knows all the things that you care about or all the things you’re trying to do. People are not sitting around waiting for pearls of wisdom to fall out of your mouth. They have other things on their mind.

HPR: On top of your background in education and politics, you are also a frequent political commentator for CNN and PBS Newshour, and a Senior Fellow and national spokesperson for What Works Cities. Particularly in this time of political divisiveness and a global pandemic, what are some of the core functions of journalism? Why is it so important to stay informed?

MN: We appear to be in one of the most unique times in American history. Publicly, much of this goes back to Donald Trump’s inauguration, with words like “alternative facts” and “fake news.” That leads to a lot of confusion, consternation, anger, and disruption — a questioning of the validity of institutions and the undermining of the free press.

Where do people get their news? Which news is the truth? You can watch a number of different newscasts in the course of a night — one covers a story one way and one covers the story another way. Back in the day, when there were around three major TV channels — NBC, ABC, and CBS — I didn’t have to worry whether Walter Cronkite was telling me the truth. I didn’t worry whether Ed Murrow or David Brinkley was telling me the truth.

Today, it’s like 31 flavors of whatever you want. You can find whatever news you like to repeat to you everything that you already believe. Well, how do we learn? How do we have a decent discussion? We’ve got people in the United States of America convinced that wearing a mask is not good for you, or that it actually might be bad for you, or that it doesn’t matter. There’s scientific evidence. It’s like people are questioning whether the earth is round. I mean, do we have to have a debate whether or not two plus two still equals four?

Like I said, people are busy, even pre-pandemic, but then you put on top of it a once-in-a-hundred year pandemic and everybody’s stuck in their house. I’m on day 200 of lockdown — I’ve got a countdown going — I’ve been in the house for 224 days.

It’s just crazy. So no wonder people are frustrated, confused and stressed and no wonder mental health issues are on the rise. One day you’re running around, doing whatever you’re doing, and then the next day, it’s like “Oh no, you need to stay in the house, and we’ll tell you when you can come back out.”

HPR: Could you explain what prompted you to launch Cities United and speak towards the importance of collaboration among individual cities and communities, especially when it comes to violence and crime?

MN: When I was still in office, I partnered with Dr. William Bell at Casey Family Programs, Mitch Landrieu, my very good friend from New Orleans, and Clarence Anthony at the National League of Cities. We in Philly, certainly New Orleans, and many other cities — Mitch Landrieu and I talk about this a great deal — face the challenge of violence in our cities, especially disproportionately in the Black community. He and I and a few others were pretty outspoken about these issues. Some people were very nervous about it, or uncomfortable, or whatever the case may be. I said, “Well, I’m uncomfortable with kids dying in the street. I’m uncomfortable with folks killing each other.” I mean, if we’re going to be uncomfortable, let’s be uncomfortable and do something.

Now, we have a network of upwards of 150 cities in the Cities United network. The organization provides technical assistance and additional support. We’re working with city mayors and their teams — usually a person called the “city lead” — and helping them actually develop anti-violence, crime reduction plans all across the country. The fundamental responsibility of any government — city, county, state, federal — is the safety and security of our citizens. That is your number one job. I mean, I grew up in West Philly at a time of severe gang violence. I know people who have been hurt, shot, and killed. I had to do something.

HPR: What do you think are some of the most widespread myths about leadership? As a seasoned leader yourself, what is some advice you have for young leaders?

MN: A lot of times people see politicians on the news with big smiles, shaking hands, and kissing babies all day. Every day is just a party. The reality is, there are many days that are really, really great. And then there are some days that are really, really bad. And as much as I love “The West Wing,” which I’ve started to rewatch, most days are not like episodes of “The West Wing.”

But the service is so fulfilling. In many instances, the quiet moments are the really significant ones that often get done behind the scenes, that sometimes never end up in the newspaper. Then come the relationships you have with your colleagues and the camaraderie — getting to know them, their lives, things that are going on, challenges that they face — it’s a kind of esprit de corps, a “we’re all in this together” mentality. It’s a family. I tried to really encourage a family environment with my colleagues.

The resiliency of our citizens is just incredible. Again, I was governing during the Great Recession. As much as people were really, really pissed off about the things that we were doing, I think in a different kind of way, they understood it. They knew it wasn’t our fault. I didn’t create the worldwide recession; I was in my office minding my business, and then one day the whole thing turned upside down. I think people have a certain empathy and sympathy, and as much as they complain, rightfully, about the things that we were doing, they were like, “Well, what else is a guy going to do?”

With cities, leadership is real. It’s right on the ground; It’s literally and figuratively in your face. There’s no hiding. When you have fifteen inches of snow on the ground, you can’t make a speech and hope it goes away. If you’re at the supermarket, the barbershop, or walking down the street, people have things on their mind, and they want to talk to you. You have to listen. That’s a part of the job. There’s actually no job description. It is what you make it.

Image Source: Michael Nutter