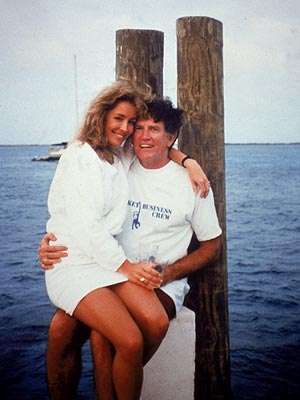

For many years, Matt Bai was the chief political correspondent for New York Times Magazine. He recently started a new job at Yahoo! News, as their chief political correspondent. He also just published a new book, All the Truth Is Out: The Week Politics Went Tabloid, which recounts the famous incident in which then-presidential candidate Gary Hart was accused of marital infidelity, famously marked by a picture of him with a woman sitting on his lap next to a unfortunately-named yacht. The media made the picture, and the juicy story that accompanied it, into front-page news, turning political journalism into full tabloid coverage and changing the course of the election. Bai’s book revisits this coverage and asks to what extent character judgements, rumors, and the personal lives of political figures should affect our public discourse.

Harvard Political Review: A large part of this book required going back to the reporters that covered the Gary Hart story and asking them to look back on it. What were their reactions when they realized you were writing a book, in many ways, about their shortcomings?

Matt Bai: I have a lot of respect for the reporters involved. None of them were trivial reporters. I knew EJ Dionne, and I met Tom Fiedler and Paul Taylor during my research. So I was interested to go back through it with all of them. And it differed with each one of them, so it’s hard to generalize. Paul and EJ had mixed feelings, and even reluctance, about re-living it. Tom had been happy to talk about it for a while.

I always try to put myself in their shoes. I never thought I couldn’t have made the same decision: I didn’t think they had done something wrong, but there were consequences that need to be examined. What surprised me was the reluctance on the part of a lot of journalists I’ve talked to not to really reflect on it at all. They decided in that moment that Hart was deficient, and they’ve never revisited that moment because revisiting it could be really uncomfortable. There have been a lot of rationales erected to prevent us as an industry from re-thinking the coverage. I’ve been surprised at how dug-in we are.

HPR: Usually, in cultural histories, enough time has passed that readers are willing to interrogate their own ideas critically. Is this the case with the media’s coverage of Gary Hart? I feel like many media consumers are still pretty interested in scandals and lying politicians.

MB: We have this idea that readers really want these stories, because they drive readership and newsstand sales: the conclusion that we reach is that we’re giving the public what they want, whether that’s right or wrong. But I don’t know. I’ve been around this country a lot, and I don’t think people are dying for more of that kind of coverage. And if you look at polls, people certainly don’t say they want more of that kind of coverage.

What we have to remember is that, when something drives ratings, it’s a spike in a relatively low amount of people: not many people are watching in the first place. And there’s a small spike in the overall viewership and we interpret that to mean proof of interest. All that’s proof of is that there’s a small group of people out there who will consume any type of salacious news. It really tells us nothing about the American electorate, and I don’t think they think we’ve ennobled our politics by going down this road.

HPR: You mentioned during your talk that Woodward and Bernstein were a model for the journalists who covered Gary Hart. What is the Woodward and Bernstein legacy today? Do people still view that sort of coverage as a goal?

MB: I think in a lot of ways, they’re still the gold standard. We still revere that moment in journalism. It’s still the high watermark. But we took the wrong lesson from it: we took it to mean that if you expose a politician’s lies, you’ll leave this great mark on history. But the reality of it is that Woodward and Bernstein were a couple of crime reporters who got a tip and followed it where it led. I think the real lesson from it is that you should go after stories, and continue to pull on them until you’ve unraveled the whole thing.

They didn’t set out to take down a president. I don’t think they would tell you that that was ever their goal or intention, and I think starting from that goal is kind of warped.

HPR: Do you have any advice for young journalists on the kind of journalism you would like them to pursue?

MB: There are a hundred different ways to pursue political journalism, and I won’t presume to tell young people what to do. But I think that you should focus on the issues you care about, and write the stories you want to read. For too long in this business, we’ve been trying to attract “readers,” as if they have a lesser mental capacity than reporters do, and you find out pretty quickly that that’s not true. I operate under the premise that you don’t need to talk down to people—they’re generally curious and they understand government and politics at a high level; it just isn’t very well explained to them.

Write the story you want to read, and explain it in the way you would explain it to your friends, and the way you would have others explain it to you. Don’t think of the reader as some estranged audience, think of him or her as yourself. Given that directive, there aren’t too many reporters out there that would seek out scandal or moral failure, because on balance, I don’t think most of us would find that important.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons