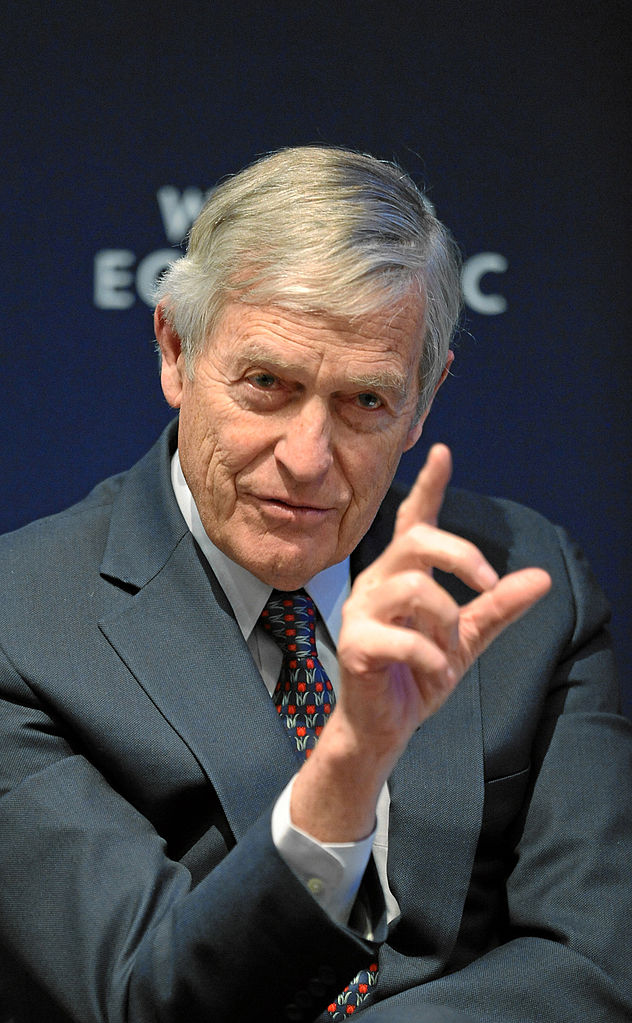

Tim Wirth was the U.S. Senator from Colorado (1987-1992) and the first Under Secretary of State for Democracy and Global Affairs (1994-1997). As Under Secretary, he worked extensively on environmental issues. From 1998 to 2013, Wirth served as the President of the United Nations Foundation.

HPR: You’ve had some harsh words for President Obama and his administration regarding their action on climate change. President Obama has hinted at the possibility of working around Congress using more executive authority. Are you optimistic that there will be follow-through on that executive action?

Tim Wirth: The President is obviously much taken, as he has to be and should be, by the gun control issue. He’ll follow right away with immigration reform. Those are both important issues. Then, there will be these continuing budget negotiations. But you can walk and chew gum at the same time. He has to do that and continue to set the table for what might be possible.

HPR: What does setting the table look like?

TW: First, you have to decide to run the interagency process. Government doesn’t work unless you make the interagency process work. That gets driven from the White House and the OMB—particularly the White House. You need to have a very senior person to drive that and make it happen. That’s exceedingly important.

The second thing he should be doing is focusing very hard on the relationship with China. We’re not going to end up with any lasting major program without a very high-level commitment with China. They’re not going to do anything without us playing. It’s the most important relationship in the world. There are so many items on the agenda that are of joint concern, ranging from efficiency to how you deal with the international negotiation to dealing with shale gas. We could make a lot of music together. That again has to be done by setting the table. Setting the table means putting together a bulletproof case on the economics of climate change, which has not been done.

Those sound like bureaucratic things to do and, in a way, they are. But that’s the stuff of government. Then, we should get into the specific items: dealing with shale, with efficiency, with black carbon.

HPR: What do you think of the Divest Harvard campaign that’s going on right now?

TW: Theoretically, it’s a good idea. But it’s very hard the way that investment portfolios are put together. If there are 20 items in a hedge fund you’re investing in and Harvard goes to the hedge fund manager and says “by the way don’t invest in number 19”, the manager can’t do that. So it’s very tricky.

But you talk about divestiture because it gives you a way to talk about the fossil fuel industry and how they’re killing the world. That’s an important thing to do. You start to have a narrative of fossil fuel. That’s a good thing to do.

HPR: As a former member of the Harvard Board of Overseers, would you cast a yes vote or a no vote on divestiture?

TW: Yes, if we can do it. But you can’t change all of your investment instruments. If the choices are there, you don’t invest in a hedge fund that’s a fossil fuel-based hedge fund.

HPR: Were you surprised by the role climate change played in the Republican primaries in 2012?

TW: Well, it didn’t. These people are in the process of being major climate science deniers. It’s remarkable, and it can’t continue.

They’re not dumb and there are a lot of people who don’t believe this, but it’s a political mantra. The entry fee right now for the Republicans is that you’ve got to be anti-abortion, for tax cuts, and anti-anything that says Al Gore on it. It used to be anti-gay and anti-immigration reform, but that’s changing. Some of these other things are going to change too. But right now, they’ve got themselves in a corner.

HPR: Will climate politics look different in 2016?

TW: I hope so. It doesn’t happen by itself. If you look at the extraordinary work that’s been done in the gay community and in the country to change that, it didn’t happen by itself but by a lot of very hard work. The civil rights movement, the women’s movement, all of these things came from outside Washington. They were very carefully organized and very carefully thought through. The same thing has to be done with the climate community. That’s hard political work that has to get done.

HPR: When you introduced some of the first cap and trade legislation in the Senate, you did it with a Republican. Has the polarization of the Senate changed today since your time?

TW: It’s gotten a lot more polarized, and you’ve got a lot people coming up from a polarized House into the Senate. I left the Senate in 1992. Normally, there’s a continuum for all the new members but that’s changed now. There are so many more of these people I’ve never met, and that’s very unusual. There’s an expression: once a Senator, always a Senator. There’s a club to it that just doesn’t exist anymore.

HPR: Is that bad?

TW: I think a lot of these people are coming to the Senate and they’ve never legislated before. The House doesn’t legislate anymore. It operates like a parliamentary system. Committees don’t work. It’s all run out of the speaker’s office. It’s all run politically. So they’re not accustomed to the process of legislating. And that’s hearings and that’s really cutting agreements and listening to the other guy and figuring out how you get from here to there. And that’s the way the Senate operates still.

HPR: You have worked in both philanthropy and politics. Which would you suggest young people who want to make an impact on social causes through their careers?

TW: I would say the most important thing is to get into politics. You have to work on a campaign. You learn more about yourself, you learn more about things, and you learn how the system works. It’s incredibly important.

It’s just incredibly important that people understand how the system works. And learning what you learn working on a campaign is intensely important.

This interview has been edited and condensed.