Lesbos, one of the larger Greek islands, lies just off the Turkish coast, not far from the city of Izmir. Formerly a popular tourist destination, at the height of the migrant crisis the island became one of the main hubs through which refugees arrived on European shores. Thousands landed on the island daily, most by crossing the narrow channel between Turkey and Greece on small, crowded rubber boats, which smugglers had loaded well past capacity.

“We would sometimes look out, and see twenty boats arriving at the same time,” recalled Anna Tascha Larsson, the Head of Communications for Lighthouse Relief in an interview with the HPR. Lighthouse, an NGO based in Sweden, began operating in September 2015 on the northeastern tip of Lesbos, where many of the boats had been arriving. In cooperation with other NGOs, as well as the local police force and fishermen, the organization helped guide approaching boats and ensure the people they were carrying landed safely.

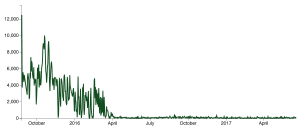

In March 2016, however, the need for help guiding in ships began to rapidly decline. As a “joint action plan” agreed on by the European Union and Turkey came into effect, the stream of refugees arriving in Greece via Turkey reduced to a trickle almost immediately. In Lesbos, which had previously seen 50-60 boats arrive daily, sometimes only a single boat now arrives in a given week. The reality facing refugees in Greece has changed dramatically—and, as a consequence, so has the work that Lighthouse and other aid organizations have taken on.

Changing Tides

The E.U.-Turkey deal was signed on March 18, 2016. In an attempt to curb the migrant crisis that had politically destabilized the continent, the European Union agreed to expedite an aid package of €3 billion euro to Turkey and to speed up talks of possible Turkish accession to the Union. In return, Turkey would work to restrain the flow of boats leaving its shores, and fight human smuggler activity more forcibly. Syrian refugees, specifically, who had already arrived in Greece would be returned to Turkey through a “one-for-one” policy: for every refugee Turkey accepted, the European Union would resettle a Syrian currently in Turkey in one of its member nations, pending security clearance.

Despite concerns by Greek and other European authorities that the deal would take time to fully enforce, the number of arrivals dropped almost immediately after the deal came into effect.

Daily Sea Arrivals in Greece

Source: UNHCR

Partly, the sharp decline was due to Turkey holding up its end of the agreement. Turkish law enforcement cleared the makeshift camps along the coast that they had previously turned a blind eye to, and moved refugees from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan to more organized camps. Likewise, the Turkish coast guard became much more vigilant, and began turning back the boats they caught departing from Turkish shores.

But more significantly, a few days before the E.U.-Turkey deal was signed, the Macedonian government closed the Greek-Macedonian border crossing. This effectively shut down the Eastern Mediterranean migration route. Previously, the thousands of migrants who left Turkey daily landed on one of a few Greek islands in the Aegean and continued to the mainland by ferry, only to immediately travel north and leave Greece through the Balkan corridor. In a week or two, they would be in Germany, Sweden, or wherever else in Europe they had hoped to reunite with families or find work.

The refugees who would arrive in Greece in the weeks that followed the border’s closing, however, were stuck. Word traveled quickly that taking a boat across the channel would now lead to a dead end: today, only about a thousand refugees land on the shores of Lesbos in a given month, and just a few thousand in Greece altogether.

Essam Daod is a child psychiatrist who runs Humanity Crew, an organization that began work on the Greek islands around the same time as Lighthouse Relief in the fall of 2015. Today, he said, the journey is far less appealing than it used to be, especially for refugees who have already lived in Turkey for some time, or have found work there.

“Risking the trip at sea may have been worth it before the deal,” he explained in an interview with the HPR, “but now that Greece is effectively detached from Europe, it is much harder to justify the dangers and the cost.”

Suspended

Even as the number of new arrivals in Greece dropped sharply, over 60,000 refugees found themselves in a bureaucratic no man’s land. In the immediate aftermath of the E.U.-Turkey deal, this led to the formation of temporary camps along the northern border of Greece, like Idomeni. Many were unable to continue the journey they had initially planned to Germany, and unwilling to return to Turkey.

Throughout 2016, with funding from the European Union, the Greek army set up large camps to house the refugees, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees put together a significant humanitarian aid operation. Still, the camps varied significantly in the resources they had available for refugees, and some were effectively operated by small NGOs rather than the UNHCR and other large organizations or the Greek authorities.

In the fall of 2016, Lucas Bertoldo, Giovanni Fontana, and Rocco Nastasi—three friends who had previously volunteered in Greece independently—started Second Tree, an NGO with the express purpose of filling the gaps left by larger organizations. With so many stakeholders, they felt, small things often fell by the wayside. “The idea was ‘no pampers? We’ll take care of it. No dentist? We’ll take care of it,’” Bertoldo said, in an interview with the HPR.

“I think the Greek Ministry of Migration Policy and the larger aid organizations mean well,” he added. “But sometimes they are disconnected from the ground.”

As the crisis evolved, aid organizations and NGOs began to provide long-term care and social support. Lighthouse, which had initially provided emergency response services on Lesbos, expanded to the mainland and began to focus on engaging with and caring for refugees who were stuck in Greece. “My first goal, when I got here, was just to make sure everyone was alive,” said Larsson. “If the refugees on the boat all survived, I did my job. Now, the problems have changed, but they haven’t become smaller. The refugees feel stranded, and are increasingly vulnerable.”

Women and children were initially prioritized for care by most organizations. Lighthouse, for example, set up preschool tents and spaces for women in a number of camps, in which staff and volunteers engaged them with various activities. Over time, it became clear that young men, who were previously seen as more self-sufficient, had been left behind by many volunteer groups—NGOs eventually began to engage with them, too.

One key goal has been to foster a sense of independence. “We try to not just go and distribute something,” Larsson said, “but to focus on giving refugees tools to use their own voice, with activities like English lessons, or resume-writing workshops for their asylum applications.”

Still, many of the younger refugees have already lost years of school: in Syria, from which many of the refugees escaped, civil war has been raging for more than six years. Returning these students to a classroom setting has been challenging.

An English lesson in the camps.

Essam Daod agreed that the work has changed substantially since he started Humanity Crew a year and a half ago. The NGO, which consists of psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals, had always focused on psychosocial support for victims of trauma. But whereas before the deal they would only interact with refugees fleetingly, conducting what they termed Psychological First Aid, they now engage with patients for months.

“Initially, when refugees came through Lesbos, they were in ‘fight or flight mode,’” Daod said. “Even if they lost family members in a war or at sea on the journey over, they would often push us away, and just ask for directions for the ferry to Athens.” Daod’s team would sometimes hear from the same refugees a month or two after they had settled down in Germany. “When their defense mechanisms went down,” he said, “and their experiences bubbled up to the surface, they would suddenly Skype Humanity Crew, asking for help.”

Today, Humanity Crew sees the same thing happening with the people they help in Lesbos. “We see Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, nightmares … some people get psychogenic seizures, similar to epilepsy, from the stress.”

As the average stay in the camps lengthened, poverty, boredom, and tensions between the different ethnic and religious groups spawned violence, drug trafficking and sexual harassment. “Young single men,” Larsson said, “might be pressured to support their family financially, which can lead to criminality.” Additionally, authorities sometimes treat Syrians better in the relocation process than refugees of other nationalities, as they are more likely to receive asylum status. This further escalates tensions, which are sometimes vented in violent outbursts.

For some, the uncertainty becomes too much to bear, and there are reports that rates of suicide and self-inflicted harm have gone up significantly in the past few months. Just a few weeks ago, as members of Daod’s team were having dinner at a restaurant in Lesbos, they heard loud shouts. They ran over, and realized that a teenage girl had jumped from the city’s old walls into the sea.

A rescue team managed to save the girl before she drowned. But when she was treated in the hospital, they saw self-inflicted wounds all over her body. “When we asked her why she did it, she just said that she wanted to die. That she couldn’t stand it anymore: not being able to shower for weeks at a time. Boarding a bus, and seeing the locals move away from her.” Daod sighed. “What do you say to a 16-year-old girl like that?”

Support in a Changing Environment

NGOs working in Greece have also faced logistical challenges. Larsson said the lack of information, as well as the constant change, have made it difficult for Lighthouse to manage its volunteer team efficiently. “The different sites vary so much that it’s hard to streamline our response. Lighthouse works in several camps, each of which has a different legal status, different refugee populations, and different organizations working alongside us.”

Larsson, Daod and Bertoldo all said that the work now requires different volunteers from those they initially had: people with specialized skills, who are willing to stay for extended periods of time. “Short term volunteers are sometimes problematic in the camps,” Larsson said, “especially with children, who need stability.”

During the winter, the Greek Ministry of Migration Policy and UNHCR ultimately ensured that most—though not all—refugees were housed in sites equipped to handle the cold. In some cases these were old, repurposed wayside hotels; in others, apartment complexes rented by the Greek government, using E.U. money. Though these were more effective than tents at sheltering their inhabitants from the weather, the move away from the camps often meant it was harder for NGOs to look after the refugees.

“Sometimes, moving meant losing access to both community and crucial services,” Larsson said. “Shelter is not the only thing that’s important. They’ve lost their homes, and really need the support and friendship that a close community can offer.” In some cases, NGOs were initially not allowed in the new sites. Moreover, in the larger camps, Médecins Sans Frontières often had a care tent set up—and as the former camp residents spread over a larger number of sites, access to healthcare often became more limited.

Liene Veide, the communications and public information officer for UNHCR in Northern Greece, conceded that despite their best efforts, opening a new site is never entirely smooth. “It was, and still is, a transition for UNHCR. When we identified or set up a new location, it wasn’t ideal from day one, and presented a new set of challenges. But ultimately, we adapted, and we do our best to make as many services and provisions available.” Many sites that used to have tents, she said, ultimately had sturdy and better-insulated residential containers.

Veide, like Larsson, said that one of their main goals has been to help refugees become more independent. One of the ways UNHCR have tried to achieve this is by setting up a system of “cash cards.” These are given to families pre-charged with money, which they can use to buy their own groceries and other essential products. “The idea is to foster a sense of agency, so they can get back to making decisions for themselves as soon as possible.”

While refugees have generally been happy with the cash cards, Veide says, they still need to know Greek to be fully independent. And, as many still hope their stay in the country will be temporary, they are unmotivated to learn.

Indeed, material improvements in the camps sometimes led to unexpected backlash from refugees. “Every time we got something new for the camp, people were disappointed,” said Bertoldo. “They said, ‘we don’t want the camps to improve; we want to leave.’”

Though movement within Europe has become much more restricted for refugees, some have placed their hopes in an E.U. program that aims to spread the burden of migration more evenly between the member nations. The process requires refugees who have already applied for asylum in Greece to submit a resume and other documents to the Greek Asylum Service, which they might then forward to various embassies in Athens. If a refugee or refugee family fits the profile a certain European country is interested in—say, a young, married mechanical engineer—they might be invited to interview at the agency, which could get them approved for residency in that country.

Still, many of the applicants have not been invited to interview so far; and even many of those who were formally accepted are still waiting for official approval.

Some NGOs have had a harder time raising funds since the dramatic photos of children stepping off packed boats have become less frequent. Small donations, on which organizations like Lighthouse and Humanity Crew depend, slowed down substantially, as the media’s attention drifted away. “Psychological trauma,” Larson said, “is just less compelling than a difficult boat landing.”

These funds, though, have become more crucial than ever: as NGOs prefer stable, long-term professionals to volunteers, their operating costs have only grown. This has been a challenge for many organizations. Lighthouse, for example, recently pulled out from a camp in which they were providing help, due in large part to financial constraints.

Daod, for his part, will be shifting Humanity Crew’s emergency aid operations primarily to Malta later this summer. As the inflow of refugees coming from North Africa has outpaced the Eastern Mediterranean route tenfold, Daod feels that Humanity Crew are currently most needed as providers of psychological first aid on rescue boats, many of which depart from Malta’s shores. Still, Humanity Crew also plan to have staff members in place for more long-term care, in Athens.

Life on Pause

Everything moves slowly, and in the meantime, the refugees in Greece wait. It is hard to make decisions beyond the present moment. Should a young family enroll their kids in Greek public schools—now technically possible—when they might not still be around in a month? “Some NGOs have organized informal education in the meantime,” Veide said, “but the sense of impermanence is a challenge for all of us.”

Even for those who do want to send their kids to schools, the system has not been easy to work with. The ongoing recession has made it difficult for Greece to support many of its own citizens, let alone refugees.

“When thousands of people were arriving in Lesbos every day, it was a total catastrophe, but there was hope,” Larsson said. “People were so relieved when they landed, and we could give them a sense that the worst was behind them.” Nowadays, she admitted, her day-to-day work makes it hard to maintain that positivity, as refugees meet obstacle after bureaucratic obstacle and become increasingly frustrated by the feeling that nothing is moving.

Still, Larsson is hopeful. She feels that a growing acceptance of their situation—even if it is accompanied by frustration—has led refugees to be more willing to create community, and to feel more settled in Greece than they had before.

Seeing a small number of their friends receive approval for relocation, she said, while fostering some jealousy, has also given many hope for their own futures.

“In the meantime,” Larsson said, “we focus on making people feel like something is happening in the camps. We can only try to make the time feel meaningful, and to do our best to prepare them for whatever they will face next.”

Image Credit: Lucas Bertoldo, Second Tree