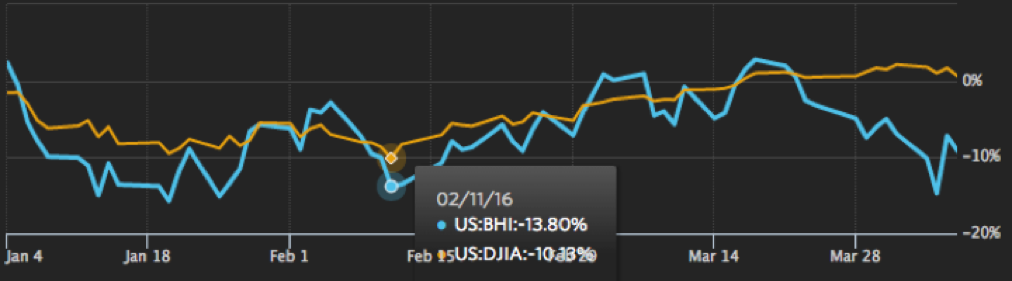

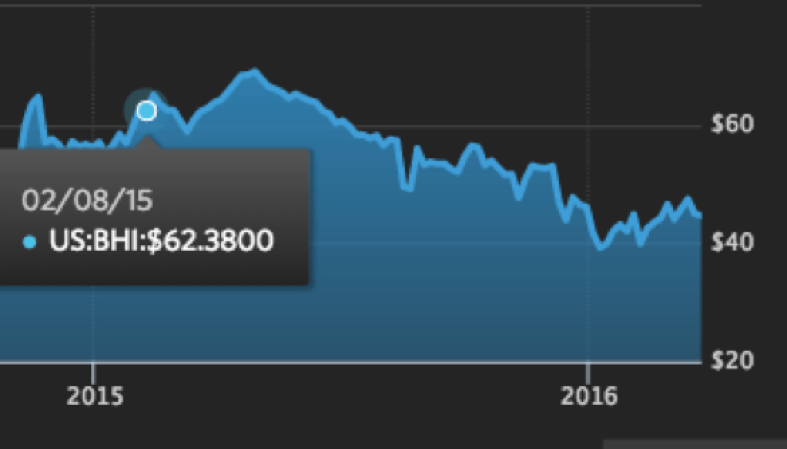

In February 2015, Harvard bought 50,000 shares of the oil field services company Baker Hughes. At the time, BHI’s stock price was close to $62. By August of the same year, the stock had dropped to around $56/share; Harvard decided to purchase 750,000 more shares, worth around $50 million in total. However, the stock has continued to drop: over the course of 2015, Baker Hughes lost $1.97 billion, and the stock is now valued at approximately $46/share. As evident from the Harvard Endowment’s February report, Harvard has gradually sold off the struggling stock, although it still retains over 400,000 shares in the company. Nonetheless, BHI has continued to falter: as seen in graph 2, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has easily outperformed the flailing oil stock. In retrospect, it is clear that Harvard made a poor investment in BHI from an economic perspective. Yet, even if it had proven lucrative, Harvard’s investment still would have been morally bankrupt.

Graph 1: BHI’s Stock Price Over the Past Year

Graph 2: BHI’s Stock Price Compared to the DJIA, Year-to-Date

Merger Between Halliburton and Baker Hughes

It is surely no coincidence that Harvard’s first investment in the oil company came within three months after news broke of a potential merger between Baker Hughes and its competitor Halliburton. In November 2014, Baker Hughes accepted Halliburton’s $34.6 billion merger proposal. A successful deal would have had tremendous ramifications for the oil sector; after all, Halliburton and Baker Hughes are the second and third largest oil field services companies, respectively. The merger, if it had been able to clear antitrust regulations, would have cut around $2 billion in research and operations costs, posing a challenge to rival Schlumberger’s perch at the top of the industry. According to financial analysts, the deal would have sent BHI’s stock price soaring to $58/share. Nonetheless, in the face of an antitrust lawsuit from the Department of Justice, the deal looks unlikely to be completed.

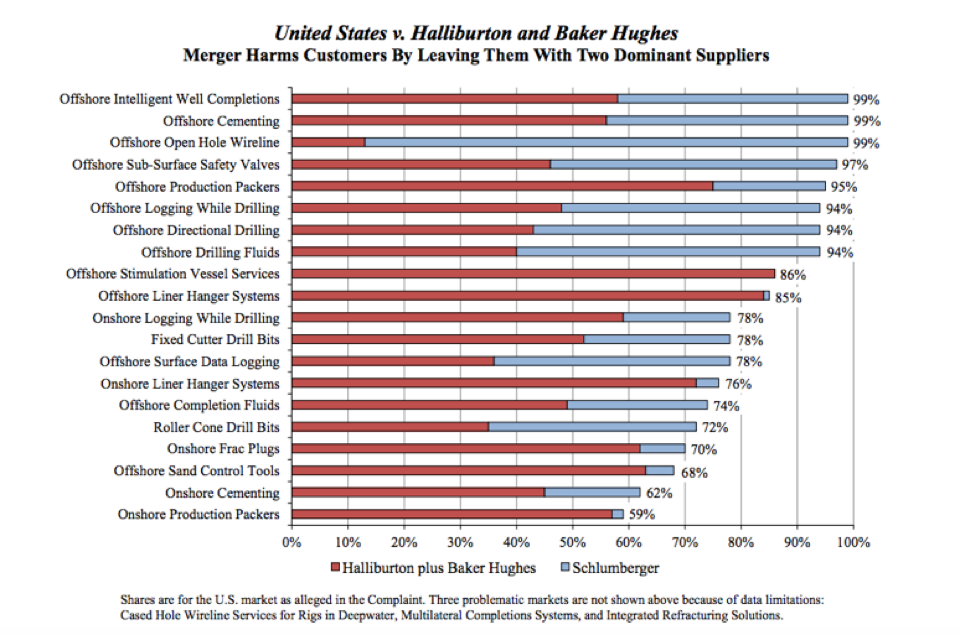

Harvard’s investment raises a number of red flags. For starters, Halliburton has had a troubling past, ranging from its role in the disastrous Deepwater Horizon oil spill in the Gulf in 2010 to its work rebuilding Iraq after the Gulf War under Chairman Dick Cheney (later Vice President of the United States). Perhaps more importantly, the merger threatened to monopolize key oil field services and was met with skepticism by anti-trust regulations in several countries. Despite spending more than $500 million on the merger in 2015 alone, Baker Hughes and Halliburton were hard pressed to convince regulatory agencies that the deal would not reduce competition in the oil field services market (see graph 3). Although the acquisition was accepted by Canada, Colombia, Ecuador, Kazakhstan, South Africa, and Turkey, other countries challenged the merger’s legitimacy. Antitrust investigators from the European Commission have continued to push back against the deal, noting that Halliburton and Baker Hughes have failed to provide critical data on the merger. Similarly, Australia’s Competition and Consumer Commission argued that the deal “may create conditions that would facilitate coordinated behavior in the market.” Several oil companies have protested the deal as well: as Total SA’s CEO Patrick Pouyanne stated in March, “Obviously when you have less competition in service providers, I’m not in favor.” Likewise, Chevron has contended that the merger would decrease competition for oil field services in Brazil, potentially causing prices to skyrocket.

Graph 3: Monopolization of Oil Field Services if Merger is Completed

(https://www.justice.gov/opa/file/838616/download)

It should come as no surprise, then, that the US Department of Justice recently voted to block the acquisition. According to Attorney General Loretta Lynch, “The proposed deal between Halliburton and Baker Hughes would eliminate vital competition, skew energy markets, and harm American consumers.” After the verdict was handed down earlier this month, both companies vowed to continue to push the deal through, asserting that the DOJ “has reached the wrong conclusion in its assessment of the transaction and that its action is counterproductive, especially in the context of the challenges the U.S. and global energy industry are facing.” Nonetheless, analysts agree that the acquisition is all but dead, with the merger’s April 30 deadline fast approaching. Even if the companies somehow convinced the DOJ to allow the merger, the European Commission would need to sign off on the deal as well, something which seems increasingly unlikely. Overall, the timing of Harvard’s investment seems to imply that the school gambled on the acquisition going through. Now that the merger has collapsed and the stock price has fallen close to 25 percent throughout Harvard’s investment, one has to question the ethics of the investment in the first place, which essentially put Harvard in the position of rooting for two corrupt oil companies to consolidate into one corrupt oil conglomerate. Opponents of divestment from fossil fuel companies often cite the economic benefits of retaining stocks in the oil industry, but Baker Hughes proves otherwise. Of course, there are countless hypotheticals to entertain. What if the merger had gone through? What if oil prices surge over the next year? What if Baker Hughes effectively utilizes the $3.5 billion consolation fee that it will receive from Halliburton when the merger falls flat? However, suppose these fanciful hypotheticals all came true. The Harvard Management Company would still have to justify investing in business practices that fly in the face of everything that Harvard is supposed to stand for.

Institutionalized Corruption

Notwithstanding Baker Hughes’ carbon footprint, the oil field services company is hardly a model for corporate integrity. On Baker Hughes’s website, CEO Martin Craighead writes, “Baker Hughes is committed to maintain the highest ethical and legal standards. We strive to comply with both the letter and spirit of applicable laws and regulations in each country in which we operate.” Apparently, Craighead views bribery and corruption as high ethical standards. In 2007, the SEC prosecuted Baker Hughes for violating the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act; ultimately, Baker Hughes was forced to pay over $44 million in fines, at the time the most substantial FCPA fee in history. Despite receiving a cease-and-desist order from the SEC in 2001 for bribing Indonesian officials, Baker Hughes continued to make illegal payments in Angola, Indonesia, Nigeria, Russia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan throughout the early 2000s. In the SEC’s 2007 report, Linda Chatman Thomsen, Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement, commented, “Baker Hughes committed widespread and egregious violations of the FCPA while subject to a prior Commission cease-and-desist Order.” Indeed, the company’s deeds were quite nefarious. In Kazakhstan, Baker Hughes gave more than $5 million to two agents to bribe state-owned oil companies. As a result of this graft, Kazahkoil granted Baker Hughes a profitable oil field services contract that yielded over $219 million in revenue up until 2006. Baker Hughes made a similar deal with KazTransOil.

The SEC also charged Baker Hughes with “violations of the books and records and internal controls provisions of the FCPA.” According to the SEC’s report, “Between 1998 and 2005, Baker Hughes made payments in Nigeria, Angola, Indonesia, Russia, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan in circumstances that reflected a failure to implement sufficient internal controls to determine whether the payments were for legitimate services, whether the payments would be shared with government officials, or whether these payments would be accurately recorded in Baker Hughes’ books and records.” For example, in Angola, Baker Hughes paid over $10.3 million to an agent, conveniently failing to certify that this money would not be used to buy off officials of Angola’s national oil company Sonangol.

On its website, Baker Hughes proudly mentions, “To commemorate Earth Day, our employees in Hassi Messaoud, Algeria, planted more than 150 trees, shrubs, and flowers including palms, Marguerite, roses, and fruit trees.” I propose that Harvard celebrates Earth Day a little differently: consider divesting from this oil field services company. Let me be clear: I do not, prima facie, support divestment from all oil companies. However, when a company bribes officials to win contracts, attempts to monopolize the oil field services’ market, hurts the environment, and has cost Harvard substantial sums of money, I think it’s time to question the Endowment’s investment procedures.

Divest Harvard is a student group that campaigns for Harvard to draw down its investments in fossil fuels, and Democracy Matters is a student group that studies the influence of money in democracy. This piece, part of a series on Harvard’s fossil fuel investments, was prepared by Justin Curtis, class of 2019.