When I think of a farm, I usually imagine an Iowa cornfield stretching for miles on end. A combine harvester spews out straw in collecting this crop; perhaps it’s destined for our plates, but more likely it will become biofuel. Indeed, forty percent of the nation’s corn supply goes to ethanol. The vast majority of the remainder, meanwhile, goes to feed livestock or to manufacture high fructose corn syrup. Only a small portion of the corn grown on these rural farms is served as corn on the cob at America’s restaurants, barbecues, and supermarkets.

Urban farms differ in every way from the corporate behemoth that Midwestern corn agriculture has become. They are small, locally owned, and grow a wide range of crops, from garlic to tomatillos, callaloo to coriander. In turn, those crops often go directly onto plates, bypassing the dizzying amount of processing that most of our food goes through.

I must admit that I had a different conception of urban farming when I started this project. I imagined a monolithic venture, an industrial enterprise merely ported to the confines of the city. Of course, I was wrong: Even within Boston, urban farms range from small community farms to rooftop gardens on top of Fenway Park to hydroponic operations growing underneath the LED lights of a shipping container.

Urban farms currently feed more than 800 million urban dwellers every year, but that number will certainly grow as the world’s population keeps increasing and urbanizing. Indeed, the UN estimated that 68 percent of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050, a larger proportion of a much larger number as the Earth’s population continues to grow more broadly. Feeding these urban dwellers will require reimagining our agricultural systems, creating a puzzle for policymakers across the globe.

Urban farms can serve as a piece of the answer to that puzzle; increased urban farming will improve food security, aid in environmental justice, and help beautify neighborhoods, all while increasing community happiness. Urban farms certainly need increased governmental support, but policymakers must remember one key thing: Urban farming is a highly localized endeavor, and each city must consider its own local conditions before making generalized policies.

Garlic in the Ground

Jet engines from planes departing Logan Airport roared overhead as I ambled towards the Eastie Farm, just a short walk from Maverick Square in East Boston. The farm looked out of place, sandwiched between two multi-family rowhouses along Sumner Street, but I felt strangely relaxed at the farm, standing in the springtime breeze, smelling the dirt, and observing just a small slice of these plants’ gradual growth process.

Volunteers worked to clear the space in preparation for more fruitful times. Lanika Sanders, an Americorps volunteer assigned to the site, directed the work party while telling me a little more about the farm. This land used to house an apartment building, but community members started using it as a trash dump once the apartments were torn down. A group of concerned residents petitioned the city to clean it up, and they planted some garlic once they had finished. “When the city said time to take it back, they argued that they still had garlic in the ground, so they had to give it to them for another season,” Sanders explained. Eastie Farm eventually took over the space.

One hour and several subway transfers later, the Fowler-Clark-Epstein Farm looked less out of place in Mattapan, home to more yards than skyscrapers. Sprinklers whirred about watering seedlings, and garlic plants tentatively put their leaves in the air. Still, its history echoes Eastie Farm’s. Along with Historic Boston and the Trust for Public Land, the Urban Farming Institute renovated a 19th century barn and farmhouse to serve as its offices and restarted farming on a property that had hosted farm operations as far back as the 1700s. The site lay vacant from 2013 until 2017, when the renovation project started. Currently, the UFI uses the site as a working farm, as well as the site of their well-reputed farmer training program, which has launched graduates into urban farms across the city.

Beantown Farming

Recently, the Boston urban farming scene has started to attract press attention — and a lot of it. An article in The Guardian described the city as “a haven for organic food and urban farming initiatives,” while Inhabitat declared Boston the second-best city in the United States for urban farming — just behind Austin.

Urban farms in Boston generally fall into three main categories: nonprofits like the UFI or Eastie Farm; community gardens in which individual farmer can grow whatever they want on an individual plot of land; or businesses out to make a profit. Some farms operate seasonally in traditional or rooftop gardens, while others operate all-year in greenhouses. Notable farms include Green City Growers’ rooftop farm at Fenway Park and a 2,400 square foot rooftop garden at the Boston Medical Center; smaller clusters of nonprofits, community farms, and greenhouses dot the Mattapan and Dudley Square areas. The city also hosts more than 200 community gardens and 100 school gardens.

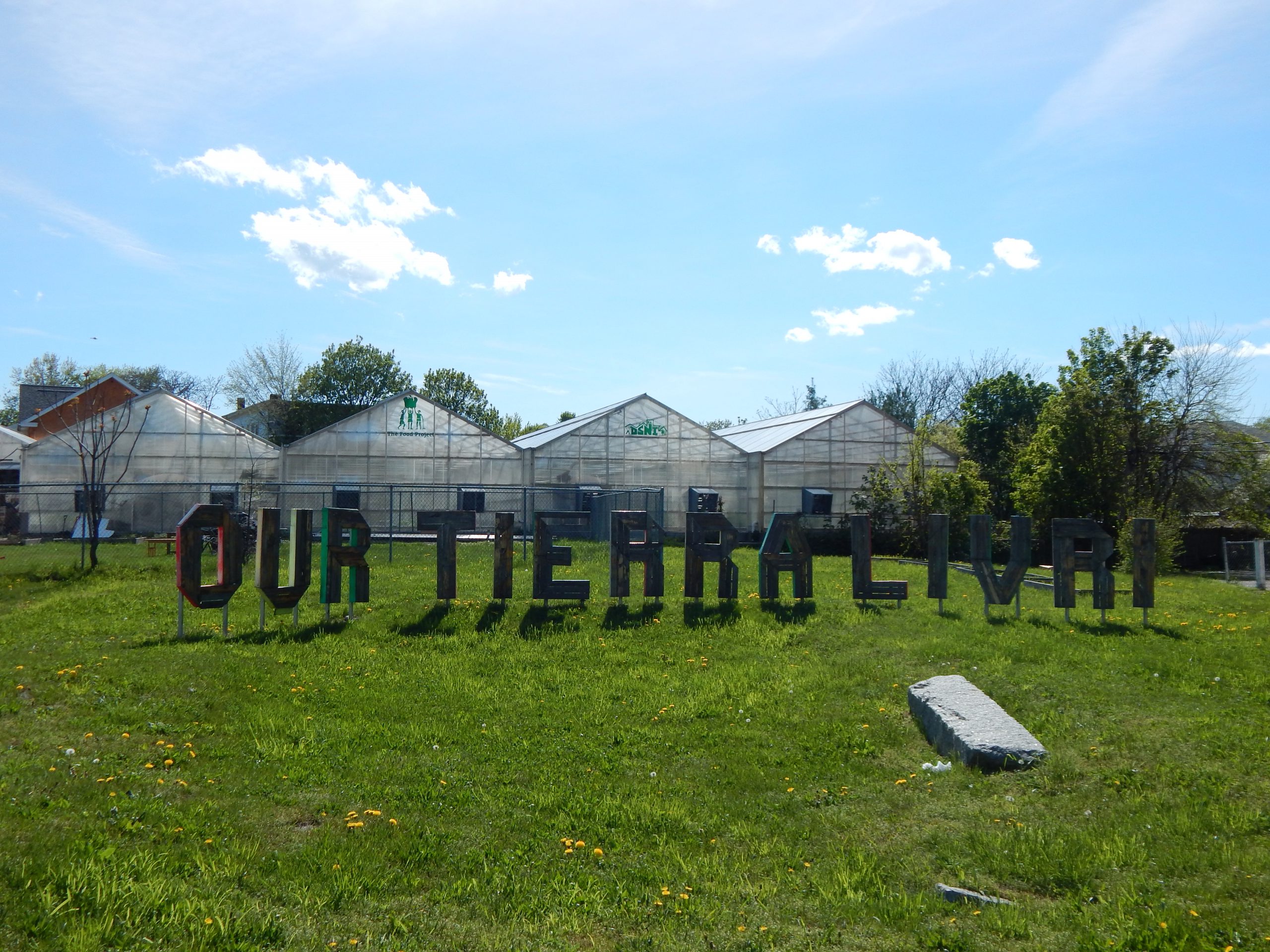

An art installation outside the Dudley Greenhouse reads “Our Liberated Land” in English, Spanish and Cape Verdean Creole.

An art installation outside the Dudley Greenhouse reads “Our Liberated Land” in English, Spanish and Cape Verdean Creole.

Boston has also spawned several agrotech startups that work in the urban farming business. Freight Farms has developed a turnkey farm entirely within a shipping container, ready to grow food as soon as it arrives at its destination. Their Greenery machine uses highly efficient LED panels, a hydroponic nursery, and artificial intelligence to create an extremely efficient automated farm system. Meanwhile, Grove Labs developed a bookshelf-sized hydroponic nursery that homeowners and business owners can control with an app.

Two major components have contributed to the general success of urban farms in Boston. On the technological side of things, a strong entrepreneurial culture means that Bostonians are willing to take risks, and the number of colleges and universities in the area gives entrepreneurs a large pool of talent to draw on to make their ideas come to fruition.

On the farming side, the 2013 passage of Article 89 changed the city’s zoning regulations to permit farming and beekeeping within the city’s jurisdiction. UFI played a major role in working out the kinks in this legislation, Patricia Spence, its Executive Director, described the process when I visited the Fowler-Clark-Epstein Farm. “We were the guinea pigs, in essence … We’ve got the water people, the inspection people, all these different entities that now have to work together in concert.” Even though some of the kinks still create problems, Boston farmers do not have to worry about the legality of their farms or greenhouses, unlike urban farmers in other cities who have to acquire permits on a case-by-case basis.

Out of the (Food) Desert?

The people I spoke with had differing motivations for entering the urban farming field. Spence remembered the importance of family in getting her start in urban farming. As we walked around the Fowler-Clark-Epstein farm in Mattapan, she recounted her story. “My grandfather farmed every piece of the property he owned in Roxbury, and we certainly ate from the yard. My mom and dad bought a vacant lot in Dorchester, and my dad grew food there all summer long. The passion comes from that vantage point.”

Karen Washington, meanwhile, remembers being galvanized by then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s proposal to auction off community garden sites. “Growing in empty lots wasn’t really about food. It was about beautification, taking back our neighborhood,” Washington, a food justice activist and founder of the suburban Rise and Root Farm outside of New York City, told the HPR. “In the middle of the night, we got backstabbed when Giuliani tried to auction off 100 community gardens. Looking back, it was the best thing that happened, but during that time, it was the worst thing that happened. People were telling us we couldn’t fight city hall, but then we said collectively we could fight city hall. A group of community gardens along with your allies, you’re much stronger. You can’t work in a silo, but when you get a community behind you, you can be a lot more successful.”

However, many people at the helm of Boston urban farms got their start in urban farming after they recognized the deficiencies in both local and national food systems. Jessie Banhazl, founder of Green City Growers, read the book Omnivore’s Dilemma, which inspired her to grow food more organically and sustainably. After moving back from New York City, she also realized something about the broader food system. “Upon returning back to the Boston area, I realized that I had been living in a food desert and that I was really feeling the effects of not having access to fresh produce,” she told me. Apolo Cátala, farm manager of the OASIS at Ballou farm in the Codman Square area, realized something similar after going on sabbatical in Puerto Rico.

Many the problems in these food systems center around nutrition and public health. “Many times, people have to go outside of their own neighborhood to find something that’s fresh, that’s edible, instead of the the junk food that’s inundating our community,” Washington said. When people eat junk food instead of fresh fruits and vegetables, their health declines — researchers have linked food deserts, areas without affordable access to fresh fruits and vegetables, to increased rates of obesity and diabetes. Obesity and diabetes disproportionately impact low-income Americans and people of color precisely because low-income Americans and people of color disproportionately live in food deserts.

Boston’s food system in particular presents numerous challenges for low-income residents. Overall, Boston has 30 percent fewer grocery stores per capita than the nationwide average, and predominantly minority neighborhoods in Dorchester, Roxbury, and Mattapan have even fewer, Barbara Knecht, the farmsite development coordinator at UFI, told the HPR. A Boston Globe investigation, meanwhile, found that 40 percent of Massachusetts residents live in a food desert. Even Harvard Square, home to affluent Harvard students, is widely considered to be a food desert.

Broader questions, though, revolve around the sustainability of our food supply and its relation to population growth. America’s farmers are notoriously inefficient. They consume large amounts of water, drawing on aquifers much faster than they can be replenished, and spray an inordinate amount of pesticides and fertilizers, creating a host of environmental issues, from resistant pests to algal deal zones. Meanwhile, the problem of overpopulation is always looming. Jon Friedman, the co-founder and COO of Freight Farms, told the HPR. “Our population is set to exceed our capabilities for food production, and that’s a big, hairy program that we have to solve,” he said.

Meanwhile, Dickson Despommier, a professor at the Columbia School of Public Health, connected urban farming and climate change in conversation with the HPR. “Climate change issues require a different approach because farmers can’t move when the climate changes. They grow corn where they live now, but in twenty or thirty years they won’t be able to because the climate won’t permit it,” he noted.

By bringing fresh produce into cities, urban farming can help address the racial inequalities that characterize food access in America.

By bringing fresh produce into cities, urban farming can help address the racial inequalities that characterize food access in America.

It’s easy to imagine these problems converging in coming decades. Climate change causes refugees from low-lying areas to flock to cities, where they go hungry because rising seas have destroyed much of the world’s arable farmland. If they can eat at all, they rely on junk food because the remaining fecund land grows high-profit or subsidized crops. In its own way, urban farming can make a contribution to stop this spiral. It makes use of previously unutilized areas — especially rooftops and vacant lots — to grow more fresh, nutritious food, selling it to the communities that need it most at affordable prices.

Although urban farms do not necessarily operate under organic principles — a set of rules including prohibitions on pesticides and artificial fertilizers — many in the Boston area, including UFI and the OASIS farm, do. Those that do not are typically small, meaning that they cannot indiscriminately spray pesticides or fertilizer. The high price of water in many cities, meanwhile, has forced urban farmers to control their water usage or find new ways to get water.

Innovations in farming practices allow urban farmers to grow their produce without pesticides and fertilizers. In setting up a controlled environment for plants in a shipping container, Freight Farms has created a technology that allows plants to grow more efficiently, with inputs exactly tailored to the plants’ needs. “We’ve uncovered a world of ways that we can help the plant do what it wants to do best or do something it’s never been able to do without the use of chemicals, fertilizers, pesticides, and the like,” Friedman explained.

Beyond its environmental benefits, the green space created by urban farms also lifts property values and community spirits. Urban farming “turns urban spaces back into places where plants are being grown, where there’s oxygen being created, where there’s beautification happening,” Washington explained. “When you go from a vacant lot to an urban farm, it makes people happier.”

Banhazl added that urban farming helps to reduce emissions by decreasing the distance between the source and the consumer — a concept known as reducing ‘food miles’. “By localizing food, you cut down on all sorts of carbon emissions and use of resources [associated with] moving and trucking and distributing food from one point to another.”

Both Banhazl and Friedman emphasized the nutritional benefits of their business models. “The sooner you pick the food and then put it in your mouth, [the more] nutritional value you will get out of that plant,” Friedman explained, and the hyperlocal nature of Freight Farms’ containers (often located right next to the main consumers of the produce, such as restaurants as grocery stores) puts healthy produce into communities that need it. Furthermore, when local residents replace junk food or processed food with fresh vegetables, their health improves. “The whole idea is we’re tapping into local knowledge about healthy food and expanding it,” Knecht of the UFI explained.

High school students at Boston Latin School can learn about innovations in agrotech and experience urban farming at the Freight Farms shipping container located on their campus.

High school students at Boston Latin School can learn about innovations in agrotech and experience urban farming at the Freight Farms shipping container located on their campus.

Farming for Fairness

Every single person I spoke to emphasized food security in relation to urban farming. Many of the community gardens and nonprofits across Boston sell their produce at farm stands and farmers’ markets in their local communities, improving food access. Green City Growers donates a portion of their produce to local food banks and soup kitchens, while school gardens help provide at-risk teenagers with fresh produce in school lunches. Volunteering programs at many urban farms also provide residents with the opportunity to work with nature, which in turn encourages them to pick healthier foods when they go to the supermarket. In addition to teaching local residents how to grow their own food, the UFI’s farmer training program also helps them to develop useful skills for the workplace.

Above all, urban farms help to inspire the local community to grow their own food, which does the most to improve food access and nutrition. “The most successful thing is to inspire people to make a stronger connection to where their food comes from,” Cátala told me. “We have the ability to engage entire communities. It’s a small scale, but it’s still a scale that has a big impact, and it’s important to measure that.” Patricia Spence reiterated the importance of this point: “We say, whether you’ve got a little bit of dirt in the backyard, if you’ve got a porch, if you’ve got a windowsill, we want you growing food.”

Spence noted the impact urban farming can have beyond nutrition, citing two stories that have stuck with her. “Chris was a part of our class of 2014, and the success of our program is Chris’s story. He was reentering the workforce, he had been incarcerated. It took him a year or two to get into the program, but he went through the program in the 2014 year, lost 100 pounds, and learned what a real tomato tastes like. He became our tomato expert,” Spence began.

“He went on to work with at the Commonwealth Kitchen, this wonderful incubator of food businesses. A lot of the food trucks you see around the city actually do their food there. Chris started with working them, but after two years, he actually was like, ‘I miss the dirt!’ So he came back, and he was with us seasonally for the past two years, and he became our production manager. As of this year, I’m sorry to say, he’s not coming back because he has a full-time job at the Commonwealth Kitchen, and he’s a manager. I am sad, but it’s exactly what we want.”

“If you look at Ronald, it’s a similar story. When Ronald came to us, he was extremely quiet, a very, very quiet man, didn’t say a word. But he was a prolific journaler. He just wrote and wrote. We had to keep giving him journal books. By the end of the class, everyone was saying, ‘You talk all the time now!’ He went to work for the Commonwealth Kitchen as well, and he’s been there for four years. We had a big fundraiser last year, and he was asked to speak. This guy who didn’t speak spoke for seven minutes, I timed him, no script. He said this was the best year of his life.”

Up, Up, and Away

Dickson Despommier thinks he has another way to transform lives through food: vertical farming. Vertical farming is not a new idea, but its widespread implementation in the United States could radically change the way we think about urban farming. The HPR interviewed Despommier, who originally came up with the idea in 1999; he defined vertical farming as a “multiple-story greenhouse.” In the first few years, Despommier and the students who worked with him labored in obscurity. “We just carried out as if we were living on an iceberg somewhere floating in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, and nobody would ever read anything we did or care about what we did, so we did whatever we want. That’s the best way to approach any problem: There’s no limits on the kinds of solutions you can suggest for something as long as the solutions make sense ecologically.”

In recent years, though, larger-scale farms making true use of the vertical farm concept have sprouted up in cities across the world. AeroFarms has four farms in the city of Newark. Using what it calls a “smart aeroponic” technology, it claims to use 95 percent less water than traditional agriculture to produce yields of 370 times that of the standard model. In Japan, Spread Company recently built a vertical farm in ‘Japan’s Silicon Valley’ with automated temperature, humidity, and maintenance controls. Singapore’s Sky Greens also operates a commercially successful vertical farm, consisting of several 4-story translucent structures. Many other businesses have developed smaller-scale vertical farm operations that can take advantage of unused garage space in private residences.

At this point, three major technologies form the basis of the majority of indoor farming projects globally: hydroponics, aeroponics, and aquaponics. Despommier described each system for the HPR. In the main hydroponic technology, plant roots take in an oxygen-infused nutrient mixture through holes in PVC pipes. However, this technology suffers from competing temperature priorities: High temperatures allow more nutrients to be dissolved but also less oxygen. Despite this, the technology remains common: Freight Farms and Grove Labs both rely upon hydroponics for their systems.

Freight Farms uses innovative technologies and methods like hydroponics to grow produce within shipping containers, like this one located at UMass Darthmouth.

Freight Farms uses innovative technologies and methods like hydroponics to grow produce within shipping containers, like this one located at UMass Darthmouth.

Aeroponics solves the temperature problem in hydroponics by suspending roots in a chamber, where a nutrient-rich mist is sprayed. However, aeroponics has a valve problem: The valves involved in spraying the mist “routinely clog up, and that became a big problem with troubleshooting. It’s a mess,” Despommier said. Fortunately, a Chinese company, AEssence Grows, has developed a much more reliable valve, one that makes aeroponic systems a lot more viable, he told the HPR.

A third option has also emerged: aquaponics, a combination of aquaculture — fish farming — and hydroponics. In aquaponics, the farm owner feeds tilapia or other kinds of herbivorous fish plant material. The fish then, for lack of a better expression, excrete waste into the water. After the farmer removes the ammonia from the system, the plants take up the nutrients from the fish waste. “This sets up an internal circular economy among the fish and the plants, and you get both for the price of one,” Despommier explained. “However, the big difficulty of this is that you get two completely different growth systems to worry about at the same time. Lots of things can go wrong, and they usually do.” As a result, aquaponics technology will require a lot more innovation before it can enter the world of large-scale vertical farming.

Any vertical farming project would need to be underpinned by one of these technologies, but Despommier has his favorite. “I think aeroponics is going to take over … You can squeeze in many more plants in aeroponics than hydroponics, and aeroponics uses far less resources, including water.”

Vertical farming makes a certain amount of sense agriculturally: you can grow food up instead of just out, and you can grow year-round indoors. Whether it makes sense economically, however, is another question: A recent study found that controlled environment agriculture (a more general term for indoor growing using technologies like hydroponics) in New York City contributed minimally to food security while expending significant resources on the controlled environment itself.

The answer to the vertical farming question may not be skyscrapers filled with stories and stories of aeroponics, but small hydroponic or aeroponic systems in people’s garages. Vertical farming technology seems more suited to for-profit businesses and restaurants hawking hyperlocal produce rather than community organizations focusing on city-wide food security.

Farms from Sea to Shining Sea

Boston has become a hub for urban farming, but many of the largest American cities have their own thriving urban farming ecosystems which include and go beyond vertical farming. It would be mind-numbingly boring to list the urban farms successfully operating in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and a range of other American cities. Cities with an especially sustainable and progressive bent, such as Austin, Seattle, and Portland, are particularly well-known for their urban farms.

Urban farms in these cities generally follow the same model as Boston: a mixture of nonprofits and businesses, greenhouses, rooftop farms, and more traditional farms. Chicago’s urban farms deserve some special note: The city boasts the world’s largest rooftop farm and the country’s largest aquaponic formation. New York schools, meanwhile, have introduced programs that allow students to grow food for their own cafeterias.

Although urban farms have their place in thriving cities, they can also play a role in revitalizing Rust Belt cities suffering because of the steel industry’s decline. Nonprofits have proposed turning vacant Cleveland lots into urban farms that could serve as the centerpieces of new communities, looking to Detroit — a real-life case study for urban farming, its relationship with food and racial justice, and its role in urban renewal. The housing crisis left lots vacant across the city, and many farmers have come to view these lots as an advantage. For example, a for-profit company recently bought 1,500 vacant lots to develop into the world’s largest urban farm. Community gardens have also bought vacant lots, where African-American and Hmong communities, among others, have used the idea of urban farming to reclaim their cultural heritage, educate their youth about food issues, and regain agency in food production.

Mary Carol Hunter, a professor at the School for Environment and Sustainability at the University of Michigan, agreed to talk to the HPR about the urban farming scene in Detroit, which she noted was, of course, too expansive to cover entirely in a single interview. Initially, Detroit urban farms faced strict regulations on the sale of food, Hunter explained, but then an entrepreneur named Dan Carmody stepped in. Carmody, who took over the local food wholesaler Detroit Eastern Market, “decided it was important to have it be a community building, even though it was a for-profit business,” she said. Over the better part of a decade, the market set up a nonprofit “to help people get a business started where they could sell their food and [gave them] all the support services that went along with it … They really wanted to get a value-added product from the food.” This nonprofit has been instrumental in enabling urban farms in Detroit to create jobs and make money selling local, nutritious food, Hunter argued.

Another key figure in the thriving Detroit urban farming scene is Malik Yakini. A former teacher and principal, Yakini realized the “incredible benefit [that] came to the kids who were actually participating” in hands-on farming. Today, Yakini runs the Detroit Black Community Food Security Network, which has emerged as an important voice in Detroit’s black community on a number of issues besides food security.

A second nonprofit, Keep Growing Detroit, has also served as a key actor in growing the Detroit urban farming industry. Several years ago, the organization realized that “they would be a much more powerful group if they focused on teaching leaders in all the communities and having them bring the information back to their own neighborhood,” Hunter said. That approach, she argued, “almost single-handedly removed the neoliberalism problem of nonprofits going into underserved areas and trying to ‘help.’”

Despite this range of benefits, urban farms have not received an exclusively positive response. The Atlantic’s Conor Friedersdorf argued that vacant lots in San Francisco should be transformed into affordable housing units instead of urban farms, while the Detroit Metro Times criticized what it called “colonialism” in one urban farm giving away its produce. By giving away food for free, the farm competed with other locally owned farms that sold their produce at farmers’ markets, ultimately harming the community, the paper charged. Environmentally, meanwhile, a recent study from Sydney, Australia found that urban farms there used as much fertilizer as conventional farms.

Some of these concerns have merit, particularly ones regarding affordable housing, but each of these three critiques of urban farming examined one city in particular, and urban farming projects all have different local constraints. What may work in one city may not work in another, and vice versa. Putting community members at the helm of these urban farming projects can mitigate some of these concerns by allowing people with local knowledge to make crucial decisions around priority-setting and program design.

“By Definition Challenging”

Of course, the main challenge urban farmers face is the environment. “If any farmer or gardener says they’re an expert, they’re lying, because the only expert is Mother Nature. She will bring you to your knees if you think you know it all, she’ll test you,” Karen Washington said. For example, the OASIS on Ballou farm struggles to contend with its hillside location, Apolo Cátala told me. Meanwhile, Phoenix urban farmers must heavily irrigate their farms or use native plants since their city is located in the middle of a desert. Unsurprisingly, Phoenix’s heavily alkaline, salty, and rocky soil is quite poor.

Detroit urban farmers, meanwhile, contend with industrial pollutants such as lead and mercury in the soil left over from the city’s industrial heyday. Leaded gasoline and “manufacturing concerns were the worst pollutants, and the stuff is airborne. But [lead] is everywhere,” Hunter said. “I know that in the area of the Ambassador Bridge, there have been some [manufacturing] plants … that still release a lot of airborne toxins. People who live in those areas are reminded and encouraged not to grow leafy vegetables like lettuce because those plants actually absorb [the pollutants] directly from the air right into the food that you eat.”

Interestingly enough, artificially high water prices in Detroit also contribute to the city’s urban farming challenges. “Despite the fact that Detroit has a huge amount of quite delicious and healthy water, it costs a lot more than water should cost,” Hunter noted. Additionally, the city of Detroit has charged high fees to maintain its aging and crumbling infrastructure. “So people have had to do as much as they possibly can to set up gardens that are water-wise, and set up things like rain barrels. It’s an economic issue, not a conservation issue.”

The question of money came up time and time again. “Ask Harvard for a million dollars, some of that endowment money would be much appreciated,” joked Patricia Spence of the UFI. “We could be growing more food on more lots, but the financing has slowed up the process considerably,” she continued more seriously. Washington also turned to the question of resources. “In marginalized communities, resources are next to none. Nonexistent,” she said, skewering local politicians for not providing enough money to urban farming.

Banhazl also emphasized the difficulty associated with getting funding in the beginning stages of her business. “We didn’t have the opportunity to raise a ton of capital all at once because people were like, ‘Why would I invest in local farming? That doesn’t seem like a viable commercial business,’ which clearly it is,” she noted. The process of getting money in fits and spurts, she explained, took up a lot of her time in the formative years of Green City Growers, reducing her ability to focus on innovating and developing.

Indeed, despite the local nuance associated with urban farming, this lack of money seems to be a consistent problem across the country — even in cities with favorable regulatory frameworks. California recently passed tax incentives to convert vacant lots into urban farms, while Houston has no zoning regulations whatsoever. Yet urban farmers in Los Angeles have not taken the state up on its offer, with some landholders reportedly holding off for future development or because urban farms simply do not make enough money. Similarly, land in the Houston urban center is surprisingly expensive, and one of the few urban farms in the city worries that the city will terminate its lease in favor of future development.

Creating the Green Thumb

Obviously, a one-size-fits-all policy solution will not work for every urban farm in every city across the country, but a couple of solutions stick out. First, cities with unfriendly regulatory frameworks need to change those rules to remove the red tape that prevents urban farms from expanding or even starting.

Second, cities and states need to give more resources to urban farms, especially nonprofit farms or community gardens. The businesses selling microgreens or farms in freight containers to trendy restaurants seem to be doing pretty well for themselves, but the urban farms that directly impact local communities largely depend on grant money and donations. Tax incentives for urban farms or direct investment in these farms could do the trick.

As I plodded around the urban farms I visited, as I kneeled down to smell the first inklings of pungent garlic, as I envisioned the small seedlings growing into full-fledged plants, I realized somebody has to grow the food I eat — and that somebody is unlikely to ever be me. But if I did grow my own food, I would care so much more about what I ate and how I ate it, and if I went to a farmer’s market every weekend to hold produce in my hands, I would probably eat a lot more vegetables.

Urban farming has this effect on people. It certainly affects communities quantitatively, improving their access to healthy, nutritious food, but its impact is also more qualitative — it’s hard to calculate the value of bringing communities closer to their food sources and closer to Mother Nature.

Chris and Ronald, the two men who benefited so much from the Urban Farming Institute’s training program, exemplify this point perfectly. Going through the UFI training was “a life-altering scenario for them that got them on a transformative path,” Patricia Spence told the HPR. “I thought this job was all about food, but it’s really all about people, and food is a vehicle. We’ve been able to transform all these lives through this thing called growing food.”

Let’s grow more food.

The cover art for this article was created by Kelsey Chen, a student at Harvard College, for the exclusive use of the HPR’s Red Line.

Image Credits: Kendrick Foster / Matthew Rossi / Freight Farms / Freight Farms