Center-left parties in the United Kingdom held an iron grip on power for centuries, but the current political realm is dominated by Labour and the Conservatives. Between the inception of the Whig party in 1721 and the end of the Liberal party in 1988, the center-left produced 30 prime ministers. It seemed to be an immobile fixture of British political life, but the rise of the Labour Party in 1922 shattered this understanding and banished the Liberals to the sidelines of British politics for decades. In 1988, however, the Liberal party merged with the Social Democratic Party to form the Liberal Democrat party, and its support has been on the rise since then. Britain’s next election is set for 2022, leaving many to wonder whether the one hundred year anniversary of the center-left’s dramatic fall in 1922 will also mark the beginning of its long-awaited return. While the Liberal democrats hold only a few seats in the House of Commons, the foundations of a return to the political stage are being built.

A New Opening

The Liberal Democrats currently occupy 12 seats in Parliament, yet their polling numbers show tremendous room for growth. In a September 2017 YouGov poll, 61 percent of Labour voters and 41 percent of Conservative voters would at least consider voting for the Liberal Democrats in a future election. This balance can be attributed to the Liberal Democrats’ position as a centrist party. Conservative-leaning voters can agree with some of the Liberal Democrats’ moderate fiscal policies, and Labour-leaning voters share its social liberalism. In an interview with the HPR, University of Sussex Professor of Politics Paul Webb said that in the 1980s, as Margaret Thatcher led the Conservatives to the right, the center of the political spectrum became a wide opening for the Liberals to fill, which culminated in the creation and expansion of the Liberal Democrats. He explained that there is now “a possibility for that kind of space opening up again.”

Today, however, this center ground is created not by the Conservatives moving right, but by Corbyn’s Labour lurching left. Corbyn describes this move as “socialism for the twenty first century.” Voters who reject socialism while accepting socially liberal policies are prime targets for the Liberal Democrat party because its economic ideology is based on classical economic liberalism. High potential support among mainstream voters combined with a newly carved center space should be encouraging for Liberal Democrats. However, there are several issues to settle first.

Potential Obstacles

In 2010, the Liberal Democrats formed a coalition government with the Conservative party. The parties jointly increased university tuition fees, which proved deeply unpopular with supporters, especially young people. Prior to that fateful decision, the Liberal Democrats were polling at 34 percent, the highest level in ages. After the coalition, support plummeted to eight percent—double digits of progress wiped clean off the board. In council elections around the country, Liberal Democrat candidates were electorally slaughtered. The party lost hundreds of representatives.

There is an ongoing debate about how much of an impact the coalition continues to have on the Liberal Democrats. Thirteen percent of Liberal Democrat voters say that the party was wrong to enter a coalition, and they have not forgiven the party. This figure jumps to 37 percent for Labour voters. However, it seems that young people are starting to forgive the party. “Students are now back listening to the Liberal Democrats and joining the local university associations in very large numbers,” said Liberal Member of Parliament Tom Brake in an interview with the HPR. In general, party membership has more than doubled.

The Role of Brexit

Brexit will also play a pivotal role in the future of the Liberal Democrat party. Paul Webb explained that whether Labour stands for or against a Conservative Brexit deal will be key to determining the Liberal Democrats’ electoral fate. Labour’s Jeremy Corbyn is a long-time Eurosceptic, but he has also criticized Conservative efforts to officially withdraw from the European Union. MP Brake said that Corbyn has been campaigning in the Northern United Kingdom as a Leave supporter and in London as a Remain supporter, which has convinced both sides that Corbyn is with them. However, Brake says “there comes a point where he actually has to make a decision; he has to vote.”

Furthermore, if Brexit proceeds poorly or is drawn out for too long, then the Liberal Democrats could benefit considering their pro-European Union position. With regard to the rise of the Liberal Democrats, Webb affirmed that “if Brexit goes well, it’s surely got to be a more long term shift that could take a decade or more. If Brexit goes badly, we may know rather soon.”

While Brexit pits steep risk against reward, one sure advantage for the Liberal Democrats is that both the Conservatives and Labour are skeptical of the European Union. The Liberal Democrats can contrast themselves effectively against both parties because of their pro-European Union position. Forty-eight percent of voters opted for ‘Remain.’ This means that nearly half of all voters are left out of the current discussion between Labour and the Conservatives, and are generally pessimistic about the impending Brexit. Moreover, 43 percent of Labour voters would like to see the government reverse the results of the referendum. These are voters ripe for Liberal Democrat picking.

Campaigns and Elections

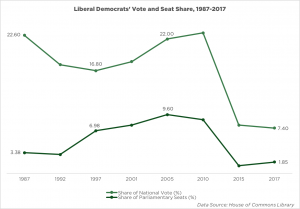

Another environmental factor that will make or break the Liberal Democrats is the British electoral system itself. The United Kingdom employs a first-past-the-post system, which means that in a given federal constituency, the candidate or party with the most votes takes the seat. This process tends to skew the proportions of votes to seats, especially for smaller parties like the Liberal Democrats. The following graph reveals the disproportionality of the current system.

In its worst year, 1987, Liberal Democrats received 22.6 percent of the national vote but only 3.38 percent of seats in the House of Commons. The most proportional year was 2005, and even then, less than half of votes for the Liberal Democrats translated into representation. The party must face the reality of working within an imperfect system, until their support is broad enough. To face this challenge, the party has adapted the electoral strategy of pouring most of its campaign resources into realistically winnable constituencies, rather than focusing on national messaging and broad popular support. In 1997, this method slightly decreased the party’s popular vote but more than doubled its representation in the House of Commons.

In conjunction with strategic constituency selection, the Liberal Democrats will need to focus on a new style of campaigning that’s viable for a party with as few as twelve seats. Professor of British Politics at Cardiff University Pete Dorey explained to the HPR that the only option for the Liberal Democrats is bottom-up, grassroots campaigning. That approach is already a strength of the party’s; MP Brake explained that the party’s MPs are strongly rooted in their communities and have longtime local profiles. This allows the Liberal Democrats to attend to constituents in an individual and local way that sometimes doesn’t work for large parties, primarily campaigning from the top-down.

Grassroots campaigning is essential to the party, but Liberal Democrats still need to be aware of tectonic shifts in other parties and the electorate in general. The Labour party is bringing in supporters at an incredible pace, which has created a dangerous divide between its socialist and moderate supporters. Jeremy Corbyn has been incredibly talented at balancing these two contradictory camps said Mark Park, Head of Innovations for the Liberal Democrats in 2001 and 2005 in an interview with the HPR. In an upcoming “high profile sequence of votes in Parliament, he will have to decide: does he, as he’s already done several times, troop through the voting lobbies in support of Theresa May … or does he oppose them?” When bridging Labour’s immense gap becomes impossible, the party will begin to splinter. Labour’s moderate, center-left voters will be vulnerable and may be looking for other options to oppose Theresa May. This will be the time for the Liberal Democrats to step in.

2022

A strength for the Liberal Democrats is party leadership. The leader at present is Sir Vince Cable, a widely respected figure in politics who has extensive experience as an economist. The issue is Cable’s age. He is 74, which means that he will be almost 80 by the next election. It is unclear whether Cable will remain party leader until 2022, or if he will hold the post only until new leadership can step in. Some experts believe that considering his popularity and experience, he will remain on; however, Mark Pack expressed that “if Vince had to stand down as party leader tomorrow, there are quite a few credible options to succeed him, and that’s definitely a strength for the party.” A new generation of Liberal Democrat leadership will sustain the party’s energy and ideology in the elections to come.

Between now and 2022, unexpected waves will roll in and out, reshaping electoral sands, but there are several promising signs for the Liberal Democrats. After five years, the bitter arguments between Labour and the Conservatives could tire the electorate and inspire a need for fresh faces. Encouragingly high proportions of Conservative and Labour voters consider the Liberal Democrats a viable option. Most importantly, the strategy of appealing to pro-EU members of the Conservatives and Labour while waiting for the collapse of Jeremy Corbyn’s delicate balancing act appears promising in a political climate with a widening center ground. Nothing is inevitable, but it appears that the Liberal Democrats are about to return to the center of British politics, and not just ideologically.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons/Richter Frank-Jurgen