Richard Foley was not surprised by Donald Trump’s election. Every day, he said, voters “drive past these abandoned hulks of buildings . . . they see the effect of NAFTA and bad trade agreements.” But while protectionism has long defined voters in the Midwest, Foley was speaking about his home state of Connecticut in an interview with the Hartford Courant. Foley, the former chairman of the Connecticut Republican party, paints an image that indicates new political headwinds in New England: the new Republican party of the region is no longer the coalition that carried the state for George H.W. Bush in 1988.

The 2016 election cycle seemed to breathe life into the long-declining “Rockefeller Republicans” that dominated the six New England states in the latter part of the 20th Century. While Trump was a far-cry from the brand of moderate ‘country club’ republicanism New England Republicans historically espoused, these moderate Republicans captured governorships in Vermont and New Hampshire in addition to the ones they already held in Maine and Massachusetts. At the federal level, Sen. Susan Collins (R – Maine), the last New England Republican in the senate, gained critical influence as the most centrist senator in the narrow Republican majority.

But this burst of moderate Republican energy in New England may represent a ticking time bomb. Economic and educational trends in the region reveal a Republican electorate eager for populism over centrism. In the coming years, this changing Republican base is poised to oust moderates from relevance in the New England GOP.

A Clear Divide

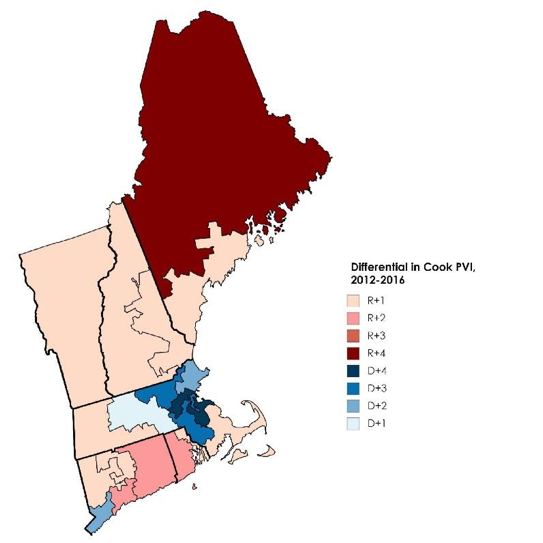

Data from the 2012 and 2016 elections shows that 13 of New England’s 21 congressional districts are trending toward the Republican party, while eight are trending toward the Democrats. The Cook Partisan Voting Index measures partisanship by numerically representing a party’s advantage in a congressional district. In a D+7 district, for example, the vote share is seven percentage points more democratic than the country as a whole. Map 1 visually represents changes in Cook PVI between 2012 and 2016, where shades of red indicate a district is trending toward Republicans and shades of blue show where Democrats are gaining ground.

Map 1: Change in Partisan Voting Index between 2012 and 2016. Source: Cook Political Report.

Trends in New England closely resemble national ones: democratic strength is increasing in urban, geographically-concentrated districts, while rural, larger districts are becoming increasingly Republican. Of the 10 congressional districts with a land area exceeding 1,000 square miles, all but one shifted toward the Republican Party between 2012 and 2016. By contrast, five of the seven most compact districts have trended toward Democrats.

Not From The Country Club

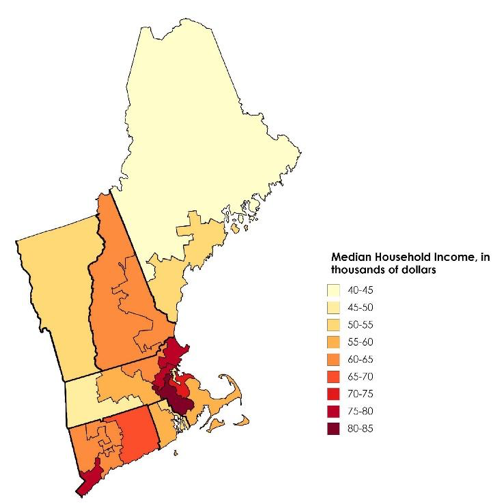

Demographic trends suggest the end of the so-called “Country Club Republican” era in New England. The wealthy suburbs of Fairfield County that vaulted the Bush family name into prominence with their strong support of Prescott Bush have gone from the most reliably Republican part of Connecticut to the only part of the state trending toward Democrats. The same story holds in Massachusetts, with the wealthy suburbs and exurbs of the Boston metropolitan area shifting left. Areas with lower incomes, meanwhile, have taken the largest leap toward Republicans.

Map 2: Districts with lower Median Household Incomes closely mirror the districts trending toward Republicans in Map 1. Source: U.S. Census

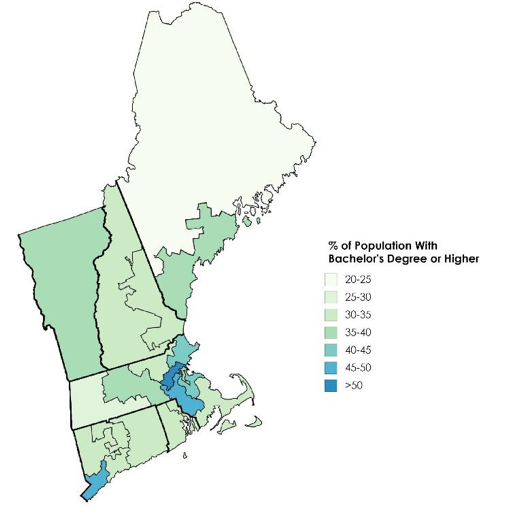

In a similar vein, the once competitive college-educated vote has tilted unevenly in the Democrats’ favor, while areas with lower educational attainment are migrating rightward. In Massachusetts, for instance, many of the well-educated exurbs that allowed Republican Governor Charlie Baker to score a narrow win in 2014 are now trending toward Democrats at the highest rates in the region.

Map 3: Districts with higher shares of Bachelor Degree holders are more likely to trend away from Republicans. Source: US Census

The First to Fall

Maine’s 2nd District provides the clearest example of the new Republican coalition in New England. At once the largest, most rural, least wealthy, and least college-educated congressional district in the region, the district’s Cook PVI swung from a D+2 advantage in 2012 to an R+2 edge in 2016. While Barack Obama carried the district by eight points in 2012, Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton by 10 points in 2016. It is also the only district in the region represented by a Republican, electing Rep. Bruce Poliquin in 2014 and reelecting him by more than nine points in 2016.

Like much of rural New England, Maine’s 2nd District grapples with many of the same challenges faced by the industrial Midwest: the opioid crisis, decline in manufacturing, and population flight have economically crippled the area.

If Maine’s 2nd District is the first to fall into Republican hands, it may represent the start of a coalition that will challenge entrenched Democratic incumbents in red-trending former industrial areas such as the Housatonic Valley in Connecticut and Western Massachusetts.

Canary in the Coal Mine

While Trump’s impressive performance in New England shocked many, past election cycles have proven that a populist message and brash personality can win in the region. Maine Gov. Paul LePage, a larger-than-life businessman with a history of controversial comments, is proof enough. Most recently, he left a threatening voicemail for a state legislator that prompted calls for his resignation. LePage’s aggressive, ‘tell it like it is’ posture differs strongly from that of Collins, the only other Republican to win statewide in Maine in recent cycles.

The divide between Collins and LePage is especially visible on immigration. Even before Trump’s presidential campaign led to choruses of “Build the Wall” at rallies and events, LePage said at a 2014 campaign event that “if we can’t build a [border] fence high enough . . . we ought to go to China and see how they built a wall.” In a sharp contrast to LePage’s nativist appeals, Collins has consistently crossed party lines to vote for pro-immigrant legislation, including the preservation of federal funding for sanctuary cities and a path to citizenship for guest workers.

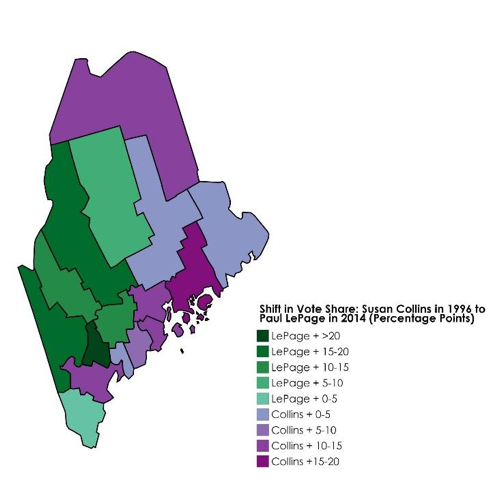

The difference between Collins and LePage hinges on the very different coalitions of support that swept them to office. Collins, frequently described as one of the “last survivors” of the moderate class of Northeastern Republicans, won her initial election by a 5.3 percentage point margin. In his 2014 reelection campaign, LePage won by a comparable margin of 4.8 points. But as seen in Map 4 below, their geographic areas of strength clearly diverged.

Map 4: Counties in shades of green show where LePage in 2014 outperformed Collins in 1996. In purple counties, Collins won a higher share of the vote. Sources: POLITICO, U.S. Election Atlas

Collins trounced LePage in the eastern part of the state, especially in the coastal counties. LePage, meanwhile, racked up massive margins in the state’s western interior, performing well with rural voters.

These contrasting coalitions have created tension between old and new Republicans in the state. When Collins was considering a run to replace the term-limited LePage in 2018, LePage lambasted her for stymying the conservative push to repeal the Affordable Care Act. Meanwhile, LePage praised another Republican gubernatorial candidate, former Health and Human Services Commissioner Mary Mayhew, who supports many of the conservative policies LePage has pursued as governor. With Collins recently announcing that she would stay in the senate, the Maine GOP has narrowly avoided an intense primary battle pitting the traditional, moderate mold of the New England Republican against the rising populist model.

Last of Their Kind?

Republican gains in New England are relatively slow, meaning it will take time before challenges to the Democratic foothold in states like Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island gain traction in federal races. But the changes in the Republican coalition are impacting the region nonetheless. In the 2016 Republican presidential primaries, all six New England states eschewed the expectation that they would support a moderate option. Trump’s populist message won five of these states handily, while culturally conservative Sen. Ted Cruz (R – Texas) prevailed in Maine’s caucus.

With high-profile gubernatorial races occurring in these states during the 2018 election cycle, the new Republican coalition may nominate populist warriors, to the chagrin of the remaining moderate Rockefeller Republicans. Within the next few election cycles, politicians like Collins and Charlie Baker could stand as the last of the long lineage of centrist Republicans in New England.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / U.S. Department of the Interior